- Essay

Fighting Intolerance by Cultivating Fascism

Ana Teixeira Pinto

Translated from French by Marie Hermet

An exploration of why ‘Judeo-Christian civilisation’ has become hegemonic in Western language, tracing the genealogy of the term while questioning its political function of concealment, appropriation, and exclusion.

Should we invoke the spirit of George Orwell to understand the present perversion of political language? ‘Lies become Truth’, as is stated in the land of Big Brother, brought to life in Orwell’s famous dystopian novel 1984. Telling lies has always been a favourite tool of those in power, everywhere and always. All national narratives, since the invention of the nation-state in 19th-century Europe, have relied to a large extent on the falsification of historical facts or, at best, on their biased use. It was presumed that heterogeneous populations could be united around heroic and legendary narratives intended to create a sense of national identity. Today, this falsification has taken different forms, unifying groups larger than those belonging to one country around common myths.

For nearly half a century in Europe and in North America, the notion of ‘Judeo-Christian civilisation’ has dominated the public sphere. Politicians, the media, and opinion makers often use this expression to describe the cultural foundation that the West has established for itself. Why has this term spread to the point of becoming a hegemonic reference, excluding all other components that helped bring forth Western civilisation?

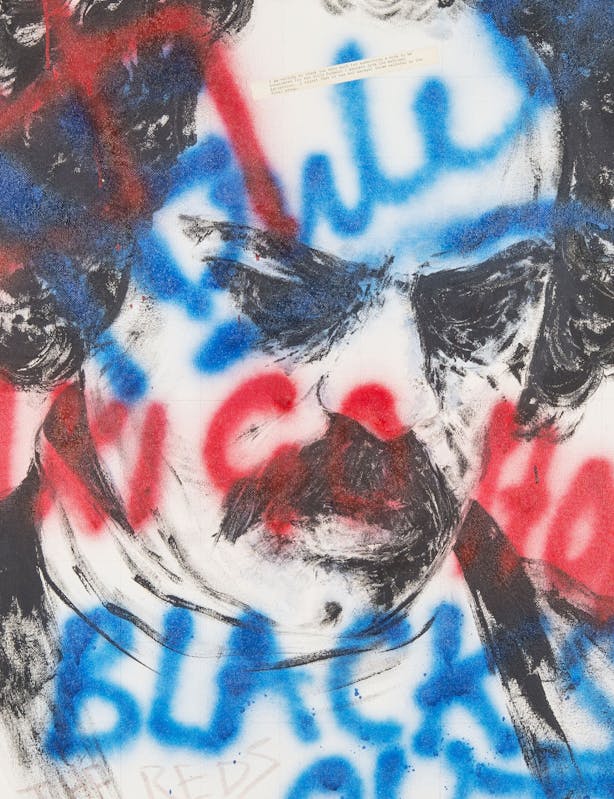

A Jew and a Muslim playing chess in 13th-century al-Andalus. El Libro de los Juegos, commissioned by Alphonse X of Castile, 13th century, Madrid.

In a recent essay, I tried to figure out the roots of this invention, which over the decades has become a regular toolbox serving questionable causes.1 Admittedly, we cannot ignore its historical foundations: they imply that it is not simply a myth. Christianity started as a dissident movement within Judaism and took some two centuries to break free from its roots; during that time many followers of the new religion were, in a sense, both Jewish and Christian. References to Jewish tradition also persisted in the biblical commentaries of Christian theological circles. However, until the present day, these interrelated developments have remained confined to scholarly discourse and theological exegesis. Therefore, it is not the term itself that should be questioned, but its seeping into everyday language, to the point where it has become another name for Western civilisation.

In a speech to the Italian Chamber of Deputies in 2022, Giorgia Meloni referred to the ‘Judeo-Christian roots’ of Europe. In France, Éric Ciotti, an ally of the Rassemblement National, wants to enshrine these ‘roots’ in the Constitution. During a visit to the Museum of the Bible in September 2025, Donald Trump declared: ‘We will protect the Judeo-Christian principles of our founding.’ Hellenism, Latin culture, and many other components of European and, more broadly, Western identity, have drowned in this maelstrom to the point of becoming invisible. No one mentions them anymore.

What does this omnipresence mean? When an expression saturates the public sphere to this extent, it raises several questions, and it is worth asking what and whom it serves. For my part, I have identified three major functions, along with a few others.

The first of these is the concealing of Europe’s shameful past. By asserting itself as exclusively Judeo-Christian, the West can effectively exonerate itself from nearly two millennia of anti-Jewish discrimination and persecution, since it could not logically have rejected a part of itself for so long. This casts a veil over Christian anti-Judaism, which, until modern times, was a constituent element in the shaping of European identity, insofar as the first otherness on which it was built was Jewish otherness, the Jew being the eternal stranger marked with the infamous stigma of belonging to the ‘deicide people’. From the 19th century onwards, during secularisation, racial anthropology replaced religion as a tool of segregation, transforming Jews from a deicide people to inferior and dangerous Semites. As we know, this racial madness culminated with Hitler, who eradicated the overwhelming majority of European Jews with the complicity or indifference of almost all Western states. However, if the people who suffered this genocide retain their open wound for a long time, those who committed it do not emerge unscathed either – far from it.

It was therefore necessary at the end of the Second World War for people from Western Europe to once again become the proponents and guarantors of the moral values they had espoused since the Enlightenment – the values they had disposed of in the smoke of crematoria. They had to restore their lost innocence by paying off the debt they had incurred to the survivors of the genocide. This restoration involved supporting the creation of the State of Israel at the expense of a people – the Palestinians – who had nothing to do with the past war; it also involved unwavering support for Israel’s policy of annexing the entire former Mandate for Palestine and its hostile construction of a buffer zone, including large portions of neighbouring countries.

While this central function of the Judeo-Christian compound should not be minimised, there are others that, taken together, have helped to define the perimeter of what is supposed to be the West. The first of these is the de-Orientalising – if I may be allowed the neologism – of the roots of Judaism. Indeed, if Judeo-Christian civilisation was ontologically Western, this would mean that the first historical expression of Abrahamic monotheism would also be Western, a simplistic and, above all, erroneous shortcut that leads us to reject any contribution from the East to the shaping of Western civilisation. The moral universals of monotheism, of which Judaism was chronologically the first proponent, thus become a purely European creation, making Europe the sole place of invention of the universal, which it translated from the 18th century onwards into a secular universalism. With this odd sleight of hand, the East then disappears from Western genealogy.

To complete the process of westernisation, it was also necessary to exclude the third function. If Judaism is the first branch of monotheistic revelation and Christianity the second, Islam is nonetheless the third, as evidenced, among other things, by the proximity of its sacred text to the biblical narrative. But while Christianity found its greatest expansion in Europe before reaching the shores of America, the Muhammadan revelation spread to the East, where it became the main if not the exclusive religion in many countries from Morocco to Malaysia. Yet the term ‘Judeo-Christian’ relegates Islam to a radical otherness. This rejection established the synonymy between the West and Judeo-Christian civilisation. In the West today, Muslims are more than ever the emblematic figure of the Other, and the dominant political rhetoric persistently frames them as such. The Judeo-Christian narrative thus leaves no room for the reality of our triptych, even though, historically, there are many examples of Judeo-Muslim correspondences and similarities between these two versions of a monotheistic religion. But history, as we know, has little to do with the construction of narratives that serve alternative purposes.

Other building blocks have been added to this relentless construction of the Judeo-Christian compound. Zionism and then the State of Israel, since its creation in 1948, needed to assert their exclusive ties to the West when facing an Arab-Muslim ‘enemy’. The Zionist doctrine, a form of Jewish nationalism that emerged in Europe in the wake of 19th-century nation-building, was developed by European intellectuals of the Jewish faith. Although Jewish, they were deeply European and, as such, imbued with an unshakeable sense of superiority over the populations of the southern shore of the Mediterranean, including Eastern Jews. It is well known that while the State of Israel needed the latter to ensure an elusive demographic superiority over the indigenous population of Palestine, its leaders – all until very recently of European origin – have relentlessly discriminated and forced Eastern Jews to assimilate into an Israeli culture built on European values. Eastern Jews had to abandon their own cultural heritage, the Arabic (or Turkish or Persian) language that was also theirs as well as the music played on the same instruments, and many other cultural markers that could have turned them into mediators instead of forcibly assimilating them into the new hegemonic Israeli culture. This operation was only partially successful, insofar as voices, not as marginal as often assumed, are rising to assert the tenacious existence of a Jewish-Arab identity that the Judeo-European steamroller has not completely managed to annihilate.

However, to understand the disaffection of many Jews of Eastern origin towards their heritage, it should be remembered that Arab nationalism in its various forms has played a powerful role. Like all forms of nationalism, the young independent Arab states, or those ruled with an iron fist by advocates of an Arab identity that excluded all other affiliations, cultivated the fantasy of ethnically and/or religiously homogeneous nations, stripped of all diversity, and denied by every means possible the Jewish dimension of their national history. They also saw the expression ‘Judeo-Christian civilisation’ as a convenient tool for erasing all traces of Judaism from their past and their culture, since Judaism now belonged solely to Europe. But here, too, history remains stubborn, and, as on the other side, not everything has disappeared from the ancient cohabitations that were not usually so conflictual.

Nevertheless, the battle for westernisation has won undeniable victories, as illustrated by the appropriation of Judeo-Christianity by the State of Israel. Like their predecessors inventing Zionism, Israeli leaders today proclaim that they are the advanced bastion of Judeo-Christian civilisation in the face of Muslim ‘barbarism’ and that their status as a regional power could protect the West from the danger that the latter represents. This may be one of the reasons why Western states support a now openly colonial policy.

Therefore, it seems that the term ‘Judeo-Christian’ is considered too useful by too many people to disappear from the landscape. For several decades it has served to obscure, appropriate, and exclude, and it still has a bright future. But it is more necessary than ever to expose its toxicity and the deceptive character of its false self-evidence in order to try to put an end to the denial of truth that is imposed on us by its use. By deconstructing it we will be able to rediscover, on both sides of a sea that was once described as common before its shores were separated, the possibilities for new hybridisations between cultures that are closer to each other than the political and religious entrepreneurs whose business is war in all its forms would have us believe. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are all instrumentalised to provide the weapons and arguments for this. Breaking free from this deadly rhetoric is the only way to bring back a semblance of reason and humanity to the march of a world whose meaning is being lost, to the great detriment of humanity itself.

Ana Teixeira Pinto

Qalandar Bux Memon

Patrick Chamoiseau