- Mission Statement

1. The Anti-Imperial Core: We Were Never Postcolonial

Stephanie Bailey, Radha D’Souza, Adam Broomberg, Françoise Vergès, Anjalika Sagar, Nour Yakoub, Gaurav Sinha

Qalandar Bux Memon questions the critical affordances and limitations of political labels such as BAME, Third World, and Global Majority.

On a hot, humid late-August monsoon day in glistening Lahore back in 2020, I headed to the National College of Arts on a rickshaw to view part of the Lahore Biennale 02: between the sun and the moon. I have made the trip to this part of the city often, particularly to the Lahore Museum, where I have found solace in the meticulous fasting Buddha statue that resides there, after many a heartbreak (of love and loss). The sculpture is among the grand works of human history but is thankfully spared that status so that one can commune with it in peace. The masterful technique that created the sculpture’s expression of blissful suffering makes it a perfect antidote to the interiorisation of oppression. The work belongs to a different civilisation and ethical realm that is not fully translatable to how we live today, but we can still glare at its transcendental aura and uncomfortably map our own pain into the Buddha’s sunken eyes.

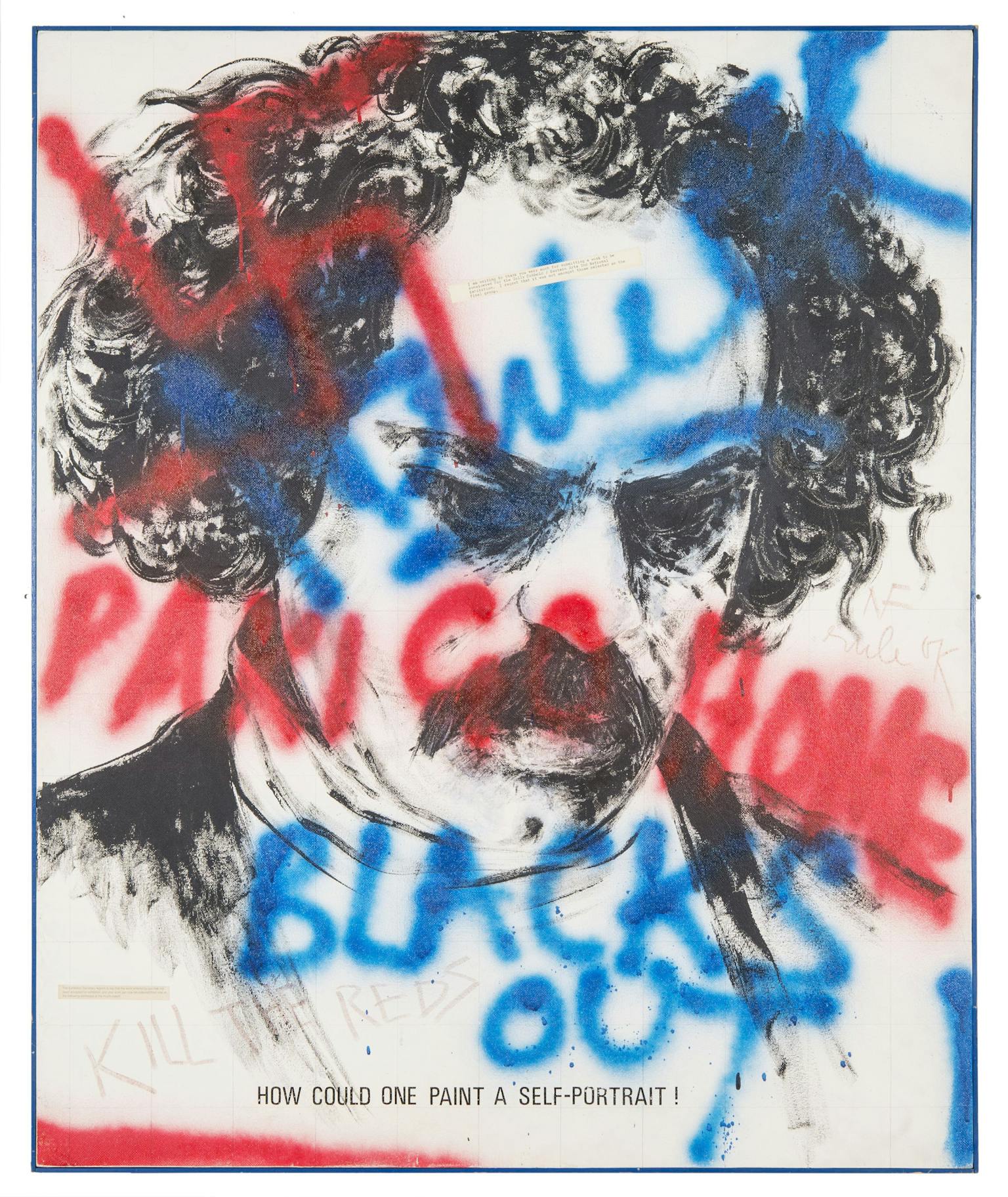

This time, however, I entered the ground-floor gallery of the National College of Art, a red-brick British-built neo-gothic building, through two opened wooden doors. Among various works by Rasheed Araeen, was a self-portrait titled, How Could One Paint a Self-portrait (1978-79), with the words ‘Paki go home’ spraypainted on it. I stared at the flat, black, white, blue, and red composition; it lacked conventional aesthetic qualities, yet its words threw me back to 1985, to North West London (where Rasheed also lived) when I was four. Most evenings, when it did not rain, I would climb up on the corner boundary wall of the garden of my father’s house and sit there looking out at the world. I would hear those words shouted by teenagers, and sometimes even adults: ‘Oi, Paki, go home!’ I would get confused whenever I heard them and climb down for a short time. Once, my father dashed over to swear back at them and told me to do likewise – he wasn’t one to take racism. My pillar of anti-racist support ended when he died a few years later.

Rasheed Araeen, How Could One Paint a Self-Portrait (1978-79). Courtesy of the artist and Grosvenor Gallery.

The other words sprayed on Araeen’s self-portrait, ‘Blacks out’, speaks of the solidarity among communities that existed during Araeen’s time, when South Asian and Black British communities understood they were not alone in facing racist structures and had to unite. Both communities would also come together in the British state’s imagination and the various guises of governamentality it conjured, when decades later the acronym BAME (standing for Black, Asian, and minority ethnic) was created. Every time I had to click or tick BAME on university forms and job applications I recoiled, even if I naively believed the preamble that there might be some benefit and ‘non-discrimination’ by identifying as such. No chance. I got no scholarships and was gainfully unemployed for most of my time in London.

This charade of allowing myself to be named from the outside, a daily epistemic violence, continued until I read Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (1952), which should be compulsory reading for all of us BAME. Fanon focuses on the Black man in relation to the colonial metropole and aims to uncover the historical, economic, and social roots of his inferiority complex. The complex that is injected into him is twofold. A discourse is created to be projected onto blackness, which is complimented by structures of discrimination that make those discourses seem true. This is also being played out today in Palestine, where the orientalist image of ‘hoards’ of ‘barbarians’ is being contrasted with a ‘free’ and ‘civilised’ Israel. What is left out of the picture is the absolute control Israel has to create the material conditions that produce this brutalising dichotomy. The fight, too, is twofold: it is a conceptual battle to sabotage racist images and concepts and a political project to change the structure of society. I read Fanon in a haze on the Northern Line tube going back and forth from Colindale to Holborn where I was studying. By the end of the book I felt cured. My discomfort, my striving to be human, was always coming up short because the human standard had been set to ‘white’ and I could never be that, no matter how many Shakespeare sonnets I memorise or passages by Rilke, Sartre, and E. H. Gombrich I cite. In the so-called great works of the western canon, I found myself always in the negative, in the margins, as a racist trope or an absence. Fanon made me realise that it was the concepts that kept defining me that needed changing, and not me.

Fanon asked racialised subjects to overcome the dehumanising effects of colonialism and racism, to assert our values, and to oppose those values imposed upon us by the racist West. He implored us to ‘leave this Europe alone’ and ‘create’ and ‘invent’ worlds of our own making.1 Reading his other books a week later, A Dying Colonialism (1959) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961), and then those by his teachers, including Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism (1950), I realised the political battle to change the structures of power was our fight. From these works, I also picked up another term of self-definition: the Third World.

The Third World in the 1960s and 70s was rich with fight. There was Selma and CLR James meeting Nkrumah in Ghana at independence, where Maya Angelou also moved for a time, while Lumumba sat with our knight Fanon to theorise the Third World struggle and its aftermath with Cabral. Che Guevara would pass through, traveling via Algeria to Dar es Salaam and into the struggle in the Congo, spending upon his return four months or so hidden at the Cuban embassy in Dar es Salaam, the same city where another beautiful knight, Malcolm X – who carried the Pan-Africanism of Marcus Garvey in his soul, Harlem renaissance Jazz in his speech, and the ethos of liberation theology, liberation everything, in his heart – conversed with South Africans in exile at the New African Hotel. Later, in the same city, Walter Rodney lived and worked as a teacher.

Earlier in 1962 in Sochi, Neruda met Faiz Ahmad Faiz, who, decades later in Lebanon, sat for drinks and poetry with Eqbal Ahmad and Edward Said. Then, in the 1980s, the activist, feminist, and novelist Nawal el Saadawi interviewed Julius Nyerere, the first president of Tanzania, back in Dar es Salaam. Nyerere talked about how ‘the plight of the Palestinians’ – ‘deprived of their own country’ – is much different and much worse than that of his generation’s struggle for independence, which is why they ‘deserve the support of Tanzania and the entire world’.2

Our struggles, our cultures, our national, or civilisational identities melt in the project of the Third World. It is a project of humanism, of expanding humanity to all. It aims to get rid of what Vijay Prashad calls ‘the international division of humanity’, of racial capitalism, or what I (following Fanon) call ‘Zones of Being and Non-Being’. Just think about what it meant for Che Guevara, an Argentinian, to fight in the Congo; for Fanon, from Martinque, to fight in Algeria; for Selma James, born Jewish in Brooklyn, to work in Trinidad and Tobago; for Faiz Ahmad Faiz to live in Beirut and edit Lotus, a magazine published by the Afro-Asian Association; for Nawal el Saadawi to see in Nyerere a brother and comrade.

To be of the Third World, to refer to oneself as a Third Worldist or a Tricontentialist, is to claim these legacies, and I took this identity up and carried it into the mid 2000s, alone at first. This was an expansive, deterritorial identity; spiritual, rather than simply secular Marxist; flexible to your region and civilisation but planetary too, with its hard masculine side tempered and radicalised by the likes of Chandra Talpade Mohanty and Gayatri Spivak, a Europeanist but born into the left culture of Bengal – and if anyone knows anything about 20th century culture, you know the richness of the left in Bengal.

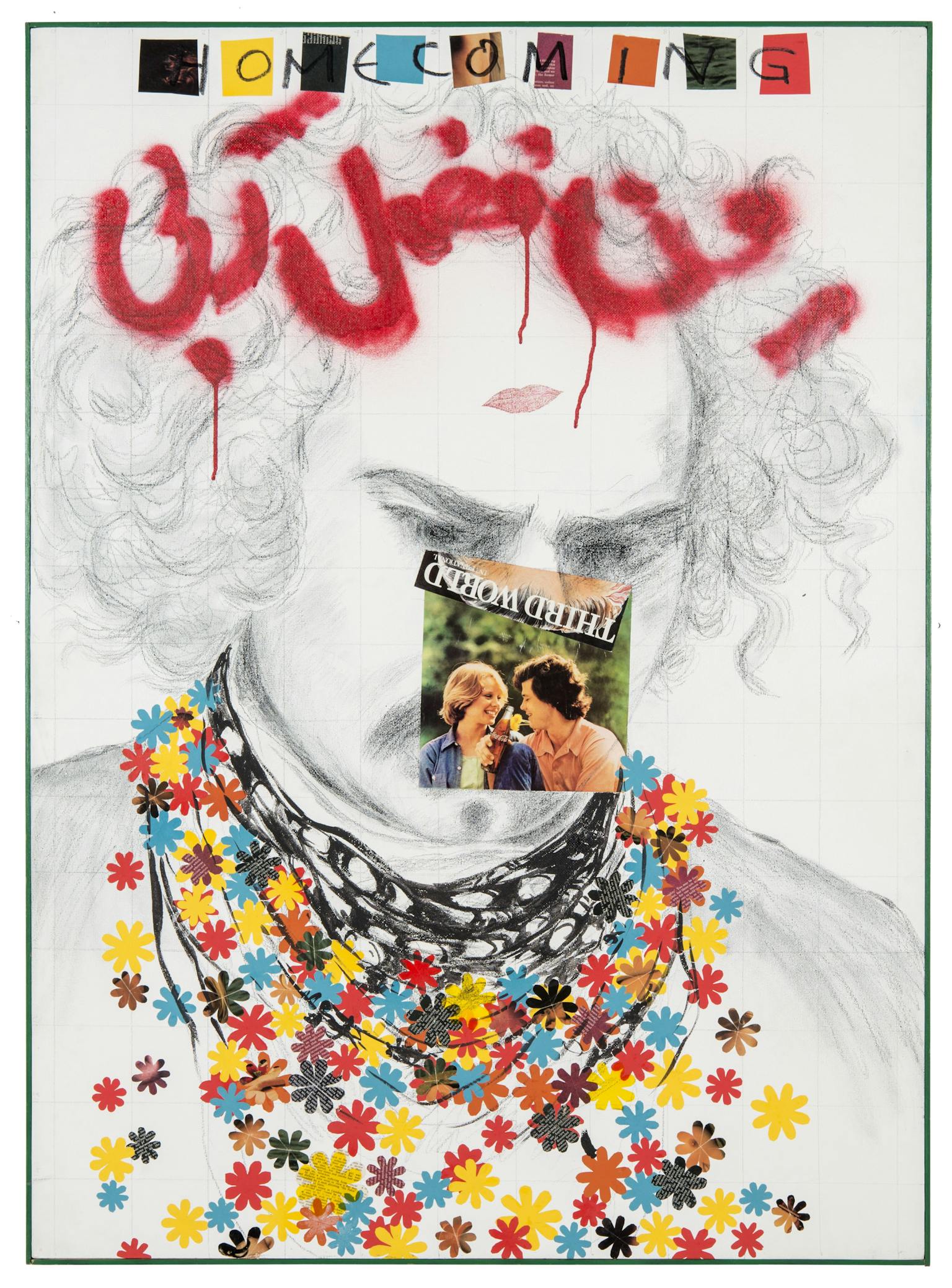

Rasheed Araeen, Homecoming (1983). Courtesy of the artist and Grosvenor Gallery.

I arrived in Lahore in the summer of 2007 from London, to de-territorise my identity and expand it in the struggle of a people. I landed in an anti-dictatorship movement in the midst of a mass uprising and repression. For two years, I threw my hat in the struggle and attended untold protests and meetings on strategies. On the sidelines of protest days there were study circles and I was often invited to speak. My work was on Third Worldism and I would outline its history and what I call, following Hans-Georg Gadamar, its ‘conceptual horizon’. After one such study circle, Sarmad A, the son of a famous Sindhi poet, took me aside to tell me about the underside of Third Worldism. ‘Look’, he said:

I agree with Third Worldism but terrible repressions have been committed in its name. Take Surkano, who gave the opening speech at Bandung but was responsible for the mass murder of Communists in Indonesia, where millions are said to have died. Or Bhutto in Pakistan, who played a Pan-Islamist and Third Worldist, bringing the Muslim world to Lahore for the second summit of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, but also led a military operation against the Baloch in Balochistan and jailed legendary anti-colonial activists.

Sarmad’s point was about the dual use and contradiction of the term: Third Worldism. A nation-state could be Third Worldist abroad and repressive, even genocidal, at home. The Baloch in Pakistan fit his point. Whether Pakistan considers itself a part of the Third World project or not, the ‘slow genocide’ of the Baloch has continued since the annexation of their territory by the Paksitani state in 1948. Today, more than 20,000 Baloch are missing. Some among the missing and extra-judicially killed have been my friends.

Over the decades while living in Pakistan, I have realised that the violence of being called a ‘Paki’, does not compare to the violence used to uphold similar racial hierarchies in the Third World. In the case of Pakistan, the Punjabi Sunni male is on top and at the bottom are the Baloch and Pakhtuns. These hierarchies are maintained with enormous structures and acts of violence, including ‘kill and dump’ (when a person is picked up by government forces, disappeared in black sites, tortured, either released or killed, and their body dumped – a local Pakistani state version of Achille Mbembe’s ‘necropolitics’). In the last month alone in Waziristan, mortar shells and drone strikes by the Pakistani state have killed tens of Pakthun children. More illustrative are the extra-judicial killings by a Karachi cop named Rao Anwar, said to number over 444 people and many of them Pakthun, who continues to face no consequences. If race, caste, and ethnic hierarchies organise everyday life in the metropole and in the Third World, then how can there be a Third World project?

Sarmad’s critique of post-independence leadership was echoed by Selma James in an interview I conducted with her. I asked about her time in Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica, where she had gone with her husband CLR James in 1958, and she described ‘middle class literates … eyeing their role in the state’, who ‘wanted to take over the British apparatus, not change it’. Concerned only with finding a place for themselves, ‘they didn't want the people involved’, James continued; ‘state power was to be exclusively for them’.3Fanon, she said, had seen this coming. Dictating The Wretched of the Earth with his last breaths, he witnessed the privileges of the comprador class multiply and corruption triumph. As he wrote in ‘The Pitfalls of National Consciousness’: ‘Today the vultures are too numerous and too voracious in proportion to the lean spoils of the national wealth. The party, a true instrument of power in the hands of the bourgeoisie, reinforces the machine, and ensures that the people are hemmed in and immobilised.’4

The problem of Third Worldism, then, lies in representation. Who speaks for the Third World and whose actions define it? For Sarmad A, it is a top-down patriarchal and classist project that has been exploited by those in power – like those whom Fanon described as the native elites – to extract from and oppress the people and the territories the Third World project claimed to liberate. This was not a term he saw himself in at all; rather, it was the sign of an ongoing betrayal.

There have been organisational and theoretical attempts to overcome the problems associated with the corruption of terms that were developed or reclaimed to support anti-colonial, anti-imperialist, and anti-capitalist struggles across times, peoples, and places. From Fanon to Freire, voices have argued for what I call ‘Third Worldist Horizontalism’ – a terrible phrase that still captures the desire to build the project of Third Worldism (and our self-identity) in a dialogical process that rejects patriarchal, top-down hierarchies.

Selma James and Spivak have been crucial to understanding this anti-patriarchal position. Both want to find space for difference while also finding space for being together and collective. Spivak articulates this with the phrase ‘We are single, singular and together’, while James thinks through this question by considering the movements of, and intersections between, race, sex, and class, as outlined in a text first published in 1973 for the radical intersectional magazine Race Today and later expanded and published as a standalone pamphlet in 1975.5

James begins by noting ‘the hierarchy of labour powers’ and corresponding wage scales that capitalism places everyone under, describing the ‘strange place’ in Marx’s Capital Volume I where ‘the relation of class to caste [is] written down most succinctly’.6 Marx describes individual labourers who are ‘appropriated and annexed for life by a limited function’ on the one hand, while ‘various operations of the hierarchy are parceled out among [them] according to both their natural and their acquired capabilities’.7 As James elaborates, race and sex are among the categories developed out of capitalism’s conditioning of its subjects to acquire certain capabilities that are then naturalised as fixed functions and characteristics, which in turn structure mutual relations. ‘So planting cane or tea is not a job for white people and changing nappies is not a job for men and beating children is not violence’, James writes, making ‘race, sex, age, nation, each an indispensable element of the international division of labour’.8

A few paragraphs later, James explains what this all means in relation to the broader class struggle:

The social power relations of the sexes, races, nations and generations are precisely, then, particularized forms of class relations. These power relations within the working class weaken us in the power struggle between the classes … Divided by the capitalist organization of society into factory, office, school, plantation, home and street, we are divided too by the very institutions which claim to represent our struggle collectively as a class.

Capital divides us while imposing a hierarchy of ‘indirect rule’ defined through categorised and quantified identities (of white over black, of male over female, of rich over poor). This hierarchy, unfortunately, does not go away in the organisations that claim to ‘represent’ us, as we have seen: the Third World state in the hands of the Third World elite becomes another particularised form that places different social identities (housewife, waged male worker, Black workers, Pakistani, Baloch, etc.) in a ‘hierarchy’ within the state and the global division of labour.

The terms ‘Global South’ and ‘Global Majority’ have appeared as contenders to Third Worldism. Both have their limits. The term Global South has been promoted by International Non-governmental organisations, with its political project set by the World Social Forum and all the limits and corruption of the NGO sector in the Third World. The NGOs represent sectors (the indigenous, women, low caste) as ‘glorified beggars’ (Spivak’s term) under whose name the NGO bosses have got rich. The term pales in comparison with the aims and conceptual richness of Third Worldism, an idea that has been built across decades by all who have participated in its project.

I worry about the term ‘global majority’, with its origins in the UK as an assertive alternative to BAME. As a term, it claims authority through a majoritarian concept of democracy, claiming, screaming: ‘we are the majority, let us have some space’. As with BAME, I imagine myself using it in applications to the Arts Council, pleading that, as part of the majority, my project should receive funding. It feels like a term for bureaucrats and elites scraping for a piece of the pie. We can use Fanon here again. In his take on Hegel's Master-Slave dialectic he insists that what the master wants from the slave is work, not recognition, but here it seems we are appealing to the ‘white master’ for a seat at the table through our majority status. But, to follow Fanon, we need to stop talking to the Master altogether and ‘create’ something ourselves. The other problem with both terms, which is shared with the problem of Third Worldism, is who speaks for the ‘global majority’ or ‘Global South’? Our differences in the hierarchy need a settlement before we move to such terms of representation. That is a political project and that is where Third Worldism still has its appeal.

Third Worldism has a history for which millions of people came together. It is an assertive political project that challenges the centrality of white supremacy head on – in the case of apartheid with a rifle in hand. That is why the British Arts Council isn’t going to ask you to identify yourself with it; why Third world elites would like you to forget it; and why the art world would like you to leave it alone and turn to passive feel-good terms like ‘global majority’.

For Selma James, each sector has to make their own power felt and those in the hierarchy with more power give it up by forging alliances for the common struggle. So, the metropole male worker has to give up their power over Third World migrant labourers in the metropole, men have to give up their power over women, and so on. Yet James is not naive to think any sector will give up power voluntarily. Instead, she argues that ‘nothing unified and revolutionary will be formed until each section of the exploited will have made its own autonomous power felt’.9 That dialogic struggle is what Rasheed Araeen’s self-portrait represents when he sprays, alongside ‘Paki go home’, the phrase ‘Blacks out’. Back then, Britain’s South Asian and Caribbean diaspora moved together, having negotiated their relation in dialogue with their common battle against fascism. Once again, we live in times too urgent for us to not unite. As we learn from history, the true majority must hold onto its collective power and organise for a common political project of liberation. If you want me, a member of the so-called global majority to stand with you, then your victory has to be mine.

Stephanie Bailey, Radha D’Souza, Adam Broomberg, Françoise Vergès, Anjalika Sagar, Nour Yakoub, Gaurav Sinha

Patrick Chamoiseau

Bani Abidi