- Essay

Cosmopoetics of Globality

Patrick Chamoiseau

Naseer Shamma is an Iraqi musician and renowned Oud player. Born in 1963 in Kut, Iraq, he graduated from the Institute of Music Studies in Baghdad in 1987, later earning a PhD in Musical Philosophy. During his illustrious career, he has received over 70 international awards and recognitions, including the prestigious Royal British Academy Award in 1998 for his contributions to the advancement of Arab music. Over the years he has composed innumerable albums and compositions for film and theatre, as well as participated in many memorable performances, such as with the jazz legend Wynton Marsalis. In 1999, he started The Arab Oud House, a school for teaching the techniques and philosophy of the oud and other Arab musical instruments. Since the inauguration of its flagship establishment in Cairo, the school has opened several branches in different parts of the world, including Abu Dhabi, Alexandria, Bagdad, and Riyadh. Beyond his artistic career, Shamma has been involved in a number of humanitarian projects and has received various awards for his commitment to humanitarian and peace initiatives.

This interview was conducted via email by Imed Alibi on 30 June 2025 following Naseer Shamma’s performance at Ibraaz on 13 June 2025. It was conducted in Arabic and translated into English by Alibi. In the interview, Shamma reflects on his long-term and ever-evolving relationship to the oud as an instrument able to unite disparate geopolitical contexts and to give expression diverse historical experiences.

Credits:

Videographer: Talie Rose Eigeland

Video Editor: Youssef Zariyat

Imed Alibi (IA): In Baghdad, the oud is a memory. In Cairo, it’s a conversation. In Abu Dhabi, it’s a performance behind closed doors. In Alexandria, it’s a breeze from the sea. Where do you feel the instrument’s silence most loudly?

Naseer Shamma (NS): The oud fills me with, and I find in it, a voice from a distant era – yet one capable of reaching toward the future. I find my truest place in the moment I listen to music and interact with it, for the oud is a spiritual language, far-reaching and lofty, and an expression of the self. It is my friend, my companion in the artistic journey, expressing the depth of the culture I believe in, conveying my feelings and thoughts in its silences and melodies. Through my journey in music and theatre, I discovered that the oud is the core of everything – a means of expression beyond the reach of words. My face and my being are clearest with the oud, for it distils in its quietness all my love, passion, and art. I am still learning from its melodies, diving into its secrets, longing for a deeper understanding of its message.

IA: You’ve called the oud a ‘companion in exile’. What does exile sound like on a good day? And on a bad one?

NS: On a good day, exile feels as if memory has found its rhythm again. The oud becomes a bridge – not only between homelands, but between who I was and who I am now. Its tone gleams like a familiar breeze through a foreign window. You play, and the distance softens; the oud doesn’t erase exile but gives it a voice you can live with. On a bad day, exile is a heavy silence – not the calm kind, but the deep, cavernous silence that follows a cry no one heard. The oud becomes a witness to the pain of disconnection. Each note feels like a question without an answer. The wood absorbs your loneliness, and when it vibrates, it trembles – not from weakness, but from truth. On such days, the oud doesn’t console you; it simply stays beside you, reminding you that pain, too, has a voice.

IA: If Ziryab were alive and scrolling through Instagram, what would he post? Would you follow him?

NS: His account would be an elegant symphony, curated with care. One day, he would post a video explaining a rare maqam (melodic mode); the next, a photo of a redesigned garment blending Andalusian elegance with futuristic lines; the next, perhaps, a slow-motion clip of a tea gathering, paired with a verse of classical Arabic poetry. Ziryab wouldn’t chase trends – he would create them. And yes, I would follow him, not just for what he posted, but for the questions hidden between the posts: What does it mean to live beautifully? Can refined taste be a form of resistance? Can culture still lead us forward? His Instagram wouldn’t be a platform; it would be a gateway.

IA: Your schools teach the oud in very different cities: war-scarred Baghdad, layered Cairo, futuristic Abu Dhabi, Mediterranean Alexandria, questioning Riyadh, and contemplative Khartoum. Do the dreams of the students sound different in each place?

NS: In Baghdad, the oud is an act of resistance – reclaiming beauty, continuity, and belonging from the grip of war. In Cairo, dreams are layered like the city itself: full of humour, boldness, and philosophy, telling colourful, paradoxical stories. In Abu Dhabi, the dreams face forward: merging the oud with electronics, visual arts, architecture – curious, experimental, asking what can the oud become? In Alexandria, dreams are poetic, infused with the sea’s longing, filled with questions about identity, exile, and home. In Riyadh, they are quiet but deep – digging for a contemporary voice rooted in the Peninsula yet speaking to the world. In Khartoum, music thirsts for identity and freedom, excavating roots in a river of intertwined cultures. Yes, the oud’s voice changes from city to city. But what unites them is the desire to belong through sound. Perhaps, across these cities, the oud has become more than an instrument – a shared voice learning to speak different dialects of hope.

IA: Can the oud live without nostalgia? Or is nostalgia its secret tuning?

NS: The oud can live without nostalgia, but it never forgets it. Nostalgia is not a condition for survival, but its secret flavour – a hidden tone among the notes. Even when we write the future on the oud, its strings remain steeped in a shadow from the past – not as a burden, but as a root.

IA: You’ve played before presidents, refugees, and ghosts. Who was the hardest audience?

NS: The ghosts. They don’t applaud, and they don’t leave. You play for them with your heart, not your hand, and they ask not for music, but for acknowledgment. Presidents sometimes allow the music to strip away politics, revealing a rare human moment. Refugees listen with their hearts, every note touching a wound or opening a window. But the ghosts, they hear you through what has been lost. That is the hardest test.

IA: Is there a question you wish journalists would stop asking you about ‘Arab identity’? And one you wish they would start?

NS: I wish they would stop asking: ‘Is Arab identity in crisis?’ We are not at a funeral. Identity is movement, transformation, renewal. I wish they would ask instead: ‘How is Arab music redefining itself without fear?’ Or ‘How can identity be a bridge, not a wall?’ When identity is framed as life, not death, it stops being a burden and becomes a promise.

IA: If you could compose a piece for a city, which would it be and what would you call it?

NS: I have written for many cities – Baghdad, Palestine, Tunisia, Rabat, Beirut, Damascus, Córdoba, Granada, Constantine, Seville, Hiroshima, Abu Dhabi – each with its own story. If I chose one now, it might be Baghdad – my first city, my deepest source of inspiration. I would call it ‘Whispers of the Great River’, for the Tigris, carrying thousands of stories.

IA: Do you think the oud’s future is in the hands of algorithms, or will it always need fingers and flesh?

NS: Algorithms may help discover new sounds, but they have no soul. The oud needs fingers that touch its strings with awareness, and a heart that beats with feeling. Music is not just notes – it is life being lived. The oud will always breathe through people, not machines.

IA: In your music, is there a note or phrase that feels like home? Or is home always moving?

NS: Sometimes a single note, a certain echo, or a brief pause feels like home. But the truth is, home moves, changes, expands. It has become like the oud: small in size, yet it carries you to countless cities, faces, and stories. Each time I play, I feel closer but never arrive. Perhaps that is music’s secret: to keep searching, not to find a place, but to create a feeling that is home.

Patrick Chamoiseau

3Phaz, Nadah El Shazly, and Jameela Elfaki

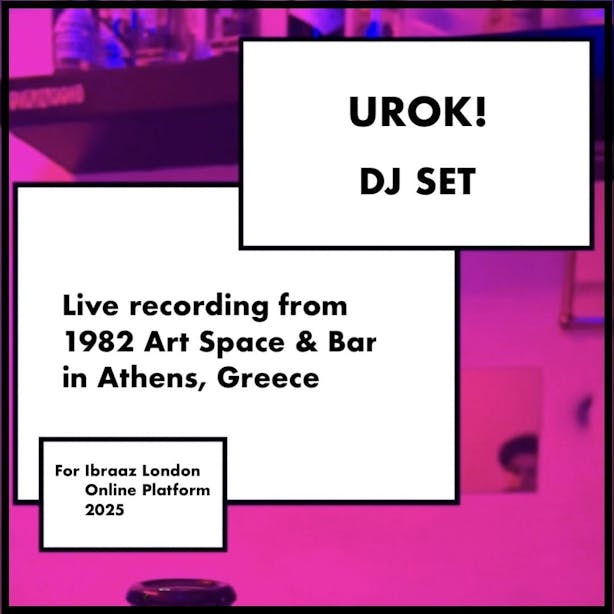

Urok Shirhan