- Screening room

Bani Abidi: Early Video Works

Bani Abidi

An exploration of Bani Abidi’s early video works and their questioning of nationalist compulsions in the context of India/Pakistan.

The News by Bani Abidi, a short film from 2001, is a staged, simultaneous telecast. There are two presenters – one Pakistani, one Indian – and their voices overlap as they present in parallel. Both characters are played by Abidi, their national identity denoted by language and dress. One speaks the Persianised Urdu of the official Pakistani state, the other the Sanskritised Hindi of the Indian. They deliver the same address, albeit in varying register and tone. It’s breaking news: a hen has laid an egg right on the border between the two countries. The film is a piece of satire, riffing off on an oft-repeated joke. Now, ask the telecasters in their verbose, stylised manner: to whom does the egg belong?

Bani Abidi, The News (2001). Courtesy of the artist.

‘There are compulsions to being part of a nation state’, Abidi once said to me in an interview.1 These iterate themselves perhaps most powerfully at the border: for a nation to understand itself better, to perform itself to its full, hyperbolic capacity, it needs to clearly delineate what it is not. India and Pakistan are well rehearsed in this choreography. Difference is maintained – with bloody consequences – in order to produce public consent toward atrocity. The border between the two countries is one of the most militarised in the world; it’s also one of the most inconceivable: climbing up the high-altitude terrain of the Himalayas, where it’s so cold there are no trees and, in parts, the ground is ice. There have been several clashes along the border since the Partition of 1947, which split the two countries on religious lines. The most recent was last year, in 2025, a ‘war’ I watched from afar, relying heavily on Indian news telecasters. My screen was overrun with Bollywood-style CGI explosions and aircraft sequences framing abstract scenes: lights blinking in the distance, as presenters rehearsed incendiary propaganda. In a historical moment overwrought with divisive narrative, watching Abidi’s films over 20 years after they were first made, their resonance is sharp as ever. In asking to whom the egg belongs, The News reveals a more enduring truth: the border itself is the absurdity, and the shared story – in all its conflicting, overlapping, and painfully familiar versions – is the inheritance.

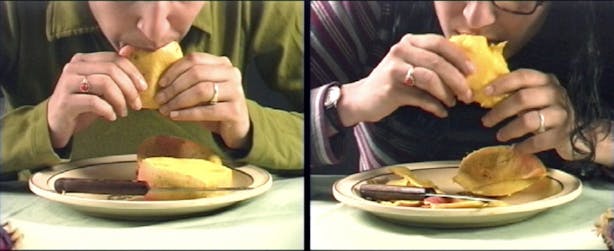

The News is from a series of three shorts, all with a similar format: two Abidis act out a new compulsion. In Mangoes (1999) they are two women of the Pakistani and Indian diaspora, eating plates of the eponymous fruit. Both have their own manner of slicing, peeling, and sucking on the flesh. They are nostalgic, reminiscing, and what begins quite touchingly turns bitter as they begin to compete over which nation has the most variety of the fruit. In Anthems (2000) the two Abidis dance, the screen is split and as each one turns up the volume on their respective stereos, their frame widens. They are in their bedrooms – again, shaded by a slight divergence of dress and design, which serve as a stand-in for place. Pakistani and Indian popular music plays; the Abidis pirouette and sway, eyes-closed, free, and purposeful.

Bani Abidi, Mangoes (1999). Courtesy of the artist.

Bani Abidi, Anthems (2000). Courtesy of the artist.

Abidi shows us that, in (for lack of a better term) South Asia, politics is posture: it is dance, pantomime, how we arrange food on our plate, how we eat it, who we choose to be friends with, and how we interact with them. We have inherited a very particular relation to the nation state, something affective and subconscious; something intangible that can only be succinctly explained through gesture. It’s hard to quantify this ‘us’. The closest approximation I can find is, perhaps, those of us from previously colonised nations without welfare states, living in the absence of tangible, juridical, and financial protection from the national infrastructure that so defines the modern realpolitik. Where social mobility remains elusive and dictated by a thousands-year old caste system, where the roads remain broken open, where the air is so thick with pollution we can stare straight into the noontime sun. Here, we are tricked and distracted by narrative instead.

In her juxtapositions, Abidi questions and exposes the fallacies in narratives of sameness and difference. We are neither identical nor are we unalike. We are ‘a people historically informed by each other’ Abidi explains.2 It’s important to remember the border is so young, less than a century old. There are an astonishing number of mango (or Mangifera indica) varieties in the subcontinent (more than 1,500 kinds). As the two Abidis discuss this variance, they touch on a shared point: what makes Indians and Pakistanis similar is that each identity, as a category and construct, contains within it an incredibly diversity. What makes us the same is that we are so different. In Mangoes, the two Abidis speak to each other in English, an inheritance of empire. In another world these two women could be speaking in Urdu. In yet another world they could be from the same town, speaking a language now unknown to us because it was erased when our sameness was first conceived and our differences solidified

Bani Abidi

Laleh Khalili, Mira Mattar, Edwin Nasr, Rahul Rao, and Skye Arundhati Thomas

Films by Bani Abidi followed by a conversation with Hammad Nasar