- Mission Statement

1. The Anti-Imperial Core: We Were Never Postcolonial

Stephanie Bailey, Radha D’Souza, Adam Broomberg, Françoise Vergès, Anjalika Sagar, Nour Yakoub, Gaurav Sinha

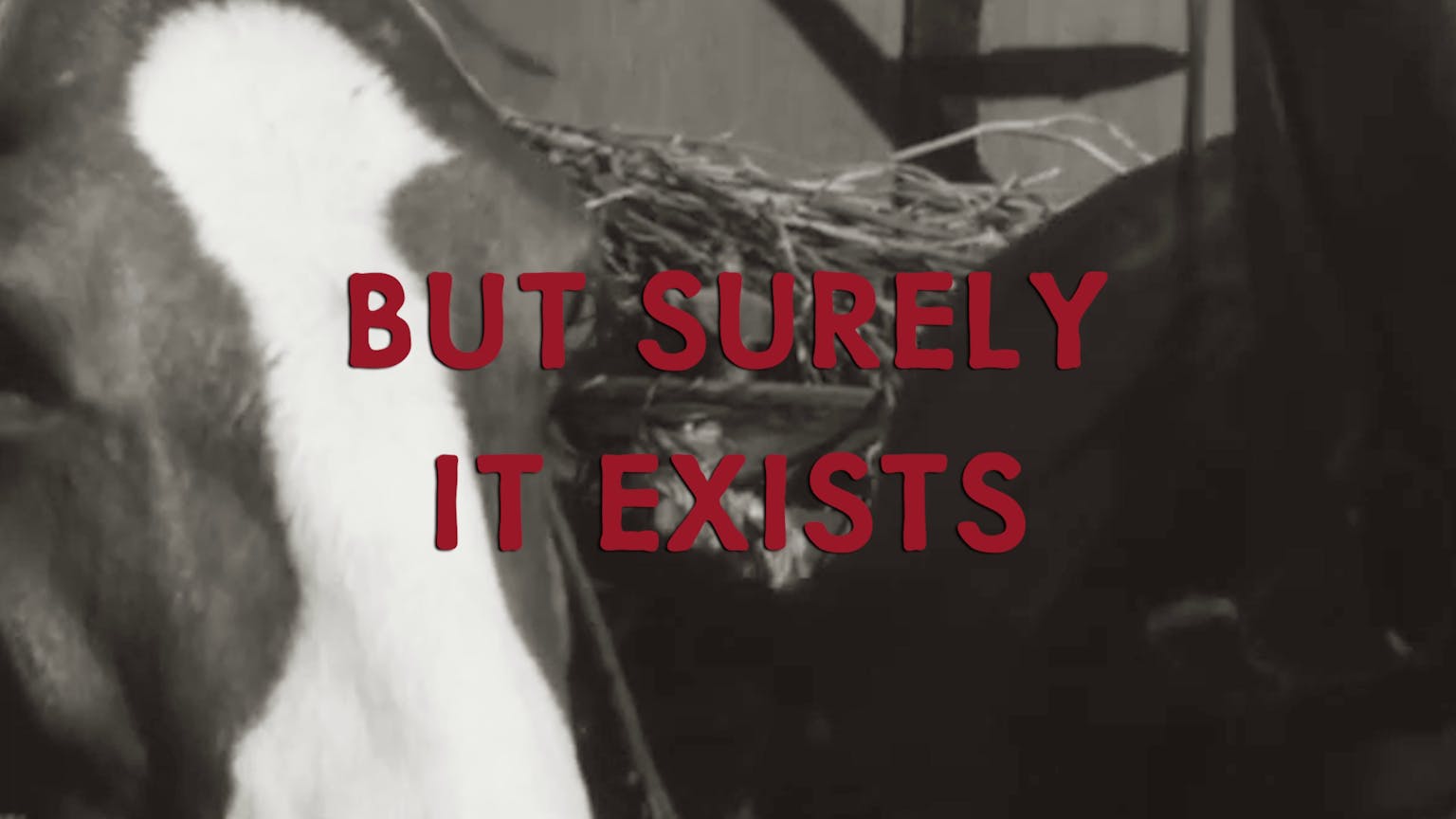

Naeem Mohaiemen stages a dialogue between the exuberant pacing of Eoghan Ryan's Carceral Jigs and the glacial roaming of his own Missing Can Of Film.

There is a moment in Eoghan Ryan’s hallucinatory Carceral Jigs (2025) where things transform into a drunken, Captain Haddock arrangement.1 A ventriloquist’s puppet tells a story that channels internal-external archetypes of Irish intoxication and memorial impulses. Perhaps you’ve heard this one? Paddy – that most Irish of names – drinks four pints at the pub every week: one for himself, one for a mate in America, one in Australia, and a fourth who is living in an emigrant destination I have now forgotten. One evening, Paddy orders only three pints and the bartender is distraught: one of his mates must have died. Drinking and emigrating away from the hard life will do that. Paddy shakes his head and says, ‘I’ve given up drinking for Lent …’ The puppet repeats the line, but no laughter greets him. His labile head shakes with hollow mirth, and he falls over again.

Eoghan Ryan, Carceral Jigs (2025). Film still. Courtesy of the artist.

Throughout the film, the puppet keeps reappearing, channeling dark and light, flopping around, never settling, never firm. In that physical apparition – one of the few elements to occupy the full 16:9 ratio of the video – I gleaned the presence-absence of a commitment to an accelerated editing rhythm, colour schema, and fluctuating ratio-proportions. We also encounter grainy surveillance of containment camps, a menacing dance floor in hyper-saturated VHS-like colour, and, at repeating intervals, furious mobs burning down homes for migrants (the conceptual focus of the piece).

There is also a manic children’s TV show that must be authentic but appears to be an extended pastiche. I was reminded of how Teletubbies (1997–2001) became a staple in the early 2000s for late-night ravers, finding new meanings while coming down from a trip. In Ryan’s film, the hopping man of the show, at a certain angle, looked like Freddie Mercury (I thought this similarity was, in part, subconsciously motivated by Mercury, a.k.a. Farrokh Bulsara, who spent a lifetime hiding his Parsi heritage from the rest of England). Another example of mistaken identity was the puppet. When I asked Eoghan if the puppet was meant to be that now-verboten racial Golliwog character of Noddy’s world, he corrected me: ‘The puppet is based on an aged, rather haggard version of Bosco, [an] Irish children’s television puppet from the 1970s through to the late ’80s, with many consecutive years of daily re-runs. So, in terms of “a puppet I/we designed”, this could be read as the national “we”, which is not incorrect but may need clarification.’2

Eoghan Ryan, Carceral Jigs (2025). Film still. Courtesy of the artist.

I have recently been thinking about Eoghan’s staccato editing rhythm, and the way he slaloms between 4:4 archival and 16:9 contemporary, rather than the more typical approach of expanding archival footage to occupy the same screen span as the more recent footage. I was mesmerised by the way the piece suddenly speeded up and assembled a hundred moments from a terrible year, under the umbrella of the racist slogan ‘Make Éire Great Again’. I was observing all this with more attention because I had walked over to the screening venue after I had spent a day adjusting the installation of my piece A Missing Can of Film (2025) for this edition of EVA International.3

Eoghan Ryan, Carceral Jigs (2025). Film still. Courtesy of the artist.

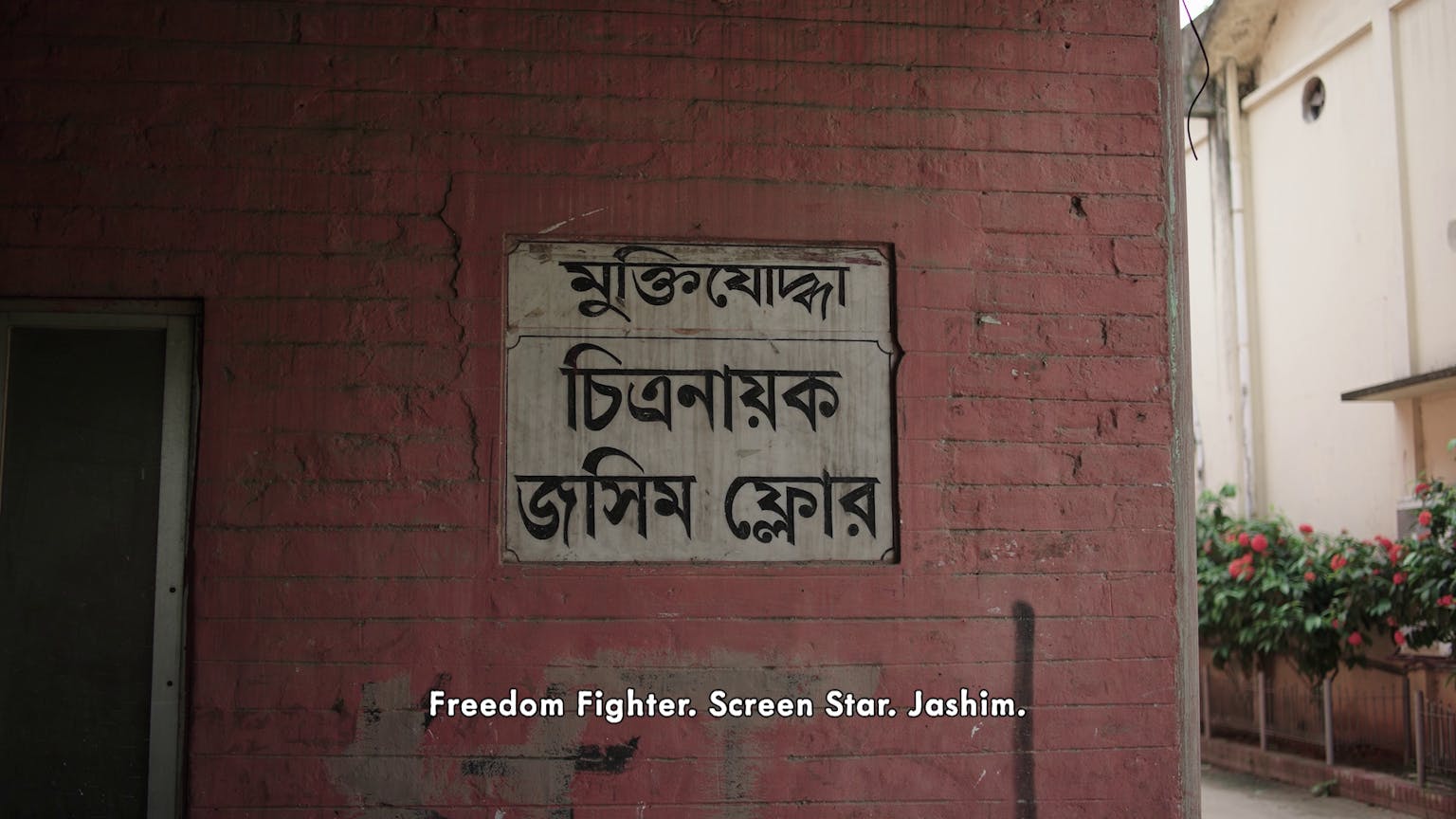

Walking into Eoghan’s space brought into intriguing contrast the slow, roaming shots of my own film and the frenetically exuberant pacing of his, both now unspooling to the same audience. Missing Can includes the slightly somnolent tracking style used in my earlier film Jole Dobe Na / Those Who Do Not Drown (2020). The hushed silence of the Dhaka Film Development Corporation during my 2024 shoot (an echo of Kolkata’s abandoned, dream-state Lohia Hospital in the 2020 film) matches and parallels my own unresolved reverence for a particular nation-state-bound film history.

In Missing Can, as we glide up the stairs of the film studio administration building, the camera pauses on a faded painting of director Zahir Raihan, the subject of the film. On a second-floor landing is a second portrait of the master, Satyajit Ray. The supertitle text interrupts the camera flow, claiming that enfant terrible director Ritwik Ghatak would be a better counterpoint to Raihan’s life of rebellious work.

Zahir Raihan disappeared at the age of 36, immediately after the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. A restless polymath, he had already directed 10 films and written 12 novels. The tensions within his cinematic forms (from neorealist social realism to mass-popular entertainment), film dialogue (from Pakistan’s ‘Islamic language’ of Urdu to the Bangladesh national language of Bengali), and political loyalties (from a nationalist project to the Soviet International) rendered him a cipher after death. He was listed among war martyrs (shaheed), but he was in fact abducted 45 days after the end of the war. Rumours circulated that a missing can of 16mm film existed, which would have embarrassed the new country’s high command. There had already been friction about the opening shots of Vladimir Lenin in Raihan’s 1971 film Stop Genocide. The new nation had its own national leader, and a growing aversion to socialism.

Naeem Mohaiemen, A Missing Can of Film (2025). Film still. Courtesy of the artist, EVA International, and Kochi Biennial.

The posthumous ambiguity around Zahir Raihan circumnavigates the way he became a symbol for a nation-state project that he may have been critical of if he had lived. Dhaka’s film industry emerged from the war shattered by the murder of Raihan, who had held promise of what Lotte Hoek called ‘cross-wing filmmaking’ within a period when ‘united’ Pakistan was about to split into two nations. Raihan started as an assistant director on Jago Hua Savera (The Day Shall Dawn, dir. A. J. Kardar, 1959), Pakistan’s only prominent neorealist production before 1971.4 Featuring East Bengali fishermen speaking an invented Urdu-Bengali patois, the film was a commercial failure. However, Iftikhar Dadi argues that the film played a ‘spectral role in subsequent cultural developments’.5

Naeem Mohaiemen, A Missing Can of Film (2025). Film still. Courtesy of the artist, EVA International, and Kochi Biennial.

The two Raihan films that are relevant to trace his later turning away from Pakistan are Jibon Theke Neya / Taken from Life (1970), made a year before the war, and Stop Genocide, completed at a feverish pace in the middle of the 1971 liberation war. Both films intercut documentary footage with filmed fiction. Newsreel footage and photographs of street marches against the Pakistan military junta are inserted between filmed scenes. Stop Genocide was completed during the war and faced what Alamgir Kabir called a ‘paucity of filmic documents of [that] gruesome massacre,’ and responded, through montage and inserts, with ‘artistic stubbornness’.6 Mahmudul Hossain likewise posits that Raihan had observed ‘Third Cinema’ and drew upon its use of documentary clips, newsreels, photographs, and statistics.7

Masha Salazkina ends her book World Socialist Cinema: Alliances, Affinities and Solidarities in the Global Cold War (2023) with a close reading of Stop Genocide. She reads in Raihan’s approach a kinship he may have had with socialist filmmakers Sergei Eisenstein, Santiago Álvarez, and Andrzej Wajda. Raihan’s close companions, and recent diary publications, have indicated a decade-long private membership in the Communist Party. Yet, if we look at Raihan’s corpus from the 1950s until the Bangladesh war, he made family dramas, commercial blockbusters, and one nationalist film – there were no additional signs of socialist cinema.

Naeem Mohaiemen, A Missing Can of Film (2025). Film still. Courtesy of the artist, EVA International, and Kochi Biennial.

In Missing Can, I wanted to trace the genealogy of Raihan’s brief, liminal socialist cinema, or what I call the ‘Socialist Stillborn’ formed under the extreme crucible of a liberation war in which the communist parties were not allowed a central role. What type of socialist cinema did Raihan develop during that war year spent in exile in India? What earlier tendrils of this had he concealed within productions while a covert member of the Communist Party? What future Bangladesh socialist cinema might have been birthed if Raihan had survived the war and moved forward with his proposal for a nationalised cinema industry in the Soviet model?

I spoke to Eoghan about some of this, and he highlighted the work of ‘unpack[ing] a life not lived but presumed, through detritus and intention; compelling the dead to speak’. Over an afternoon conversation, I asked him if he made a differentiation in his editing choices between footage of the quietly confident Irish immigrant who speaks of gardens with many flowers (a sweet analogue perhaps insufficient to this ferocious moment), and the covert video material of white ethnonationalists he spliced together. Though inconclusive, I cited the difference between Walter Heynowski and Gerhard Scheumann’s Der lachende Man (The Laughing Man, 1966), in which the interviewee mistakenly thinks he is among ‘friends’, and Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing (2012), where Indonesia’s executioners embrace the restaging of their crimes with gusto and a lack of remorse. What could a similar method be for the messy, unresolved narrative left behind by a dead filmmaker in Bangladesh?

Naeem Mohaiemen, A Missing Can of Film (2025). Film still. Courtesy of the artist, EVA International, and Kochi Biennial.

Missing Can projects my own simmering hesitation to break free of the path of quiet respect. The editing pace quickens only when it comes to Raihan’s own films, sometimes mixed as three scenes per screen, to create a split-screen homage to John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix (1966). Then, as the jumpy rhythm of those scenes ends, we politely return to the Film Development Corporation (FDC), a largely dysfunctional, state-run film studio that is meant to be a living monument to Raihan’s work. The red text on screen questions the grand flourishes in the FDC buildings – the Ray-Raihan portrait stairway, the rusted reel-to-reel machines, and the underused sound stages. Somehow, at the end of Missing Can, the scenes from a wrecked film industry sediment into a gentle critique that may not be fully faithful to Raihan’s own desire to shatter icons and deities.

Stephanie Bailey, Radha D’Souza, Adam Broomberg, Françoise Vergès, Anjalika Sagar, Nour Yakoub, Gaurav Sinha

Ala Younis

Iván Navarro