- Essay

Pakistani, Black, BAME, Other: Notes on the Politics of Naming

Qalandar Bux Memon

Ashkan Sepahvand revisits the Persian translation of Frantz Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth to consider how the word ‘duzakhian’ infuses the original with an unexpected poetics of damnation.

When the Israeli attack on Iran started, I slipped into an acute state of nymphomania. This is not an unusual response to disaster. Everything felt damned, and I wanted to feel good. My libido was rebelling against the impotence I sensed all around me since the genocide in Gaza began. The overwhelm of fascist idiocracy everywhere was unbearable. However unsustainable as a mode of action, my carnal impulse towards a chaotic aliveness – an irrational joie de vivre – helped soothe the phantom pains of political castration.

I dreaded going to psychoanalysis that week. Would my analyst, also an Iranian, share the position of many in our diaspora, who seemed to cheer the war on?

Our session started with me masking my vigilance. I asked politely if her family in Iran were safe.

‘Yes, and yours?’ she replied.

I mumbled in agreement while holding my breath, my body tense and defensive.

‘Are you happy?!’ I blurted out resentfully. It was an accusation.

After a moment of prolonged silence, she asked: ‘Are you?’

Irritated, I let go of the aggression in my body and absurdly proclaimed: ‘I AM GAY!’

She burst into laughter.

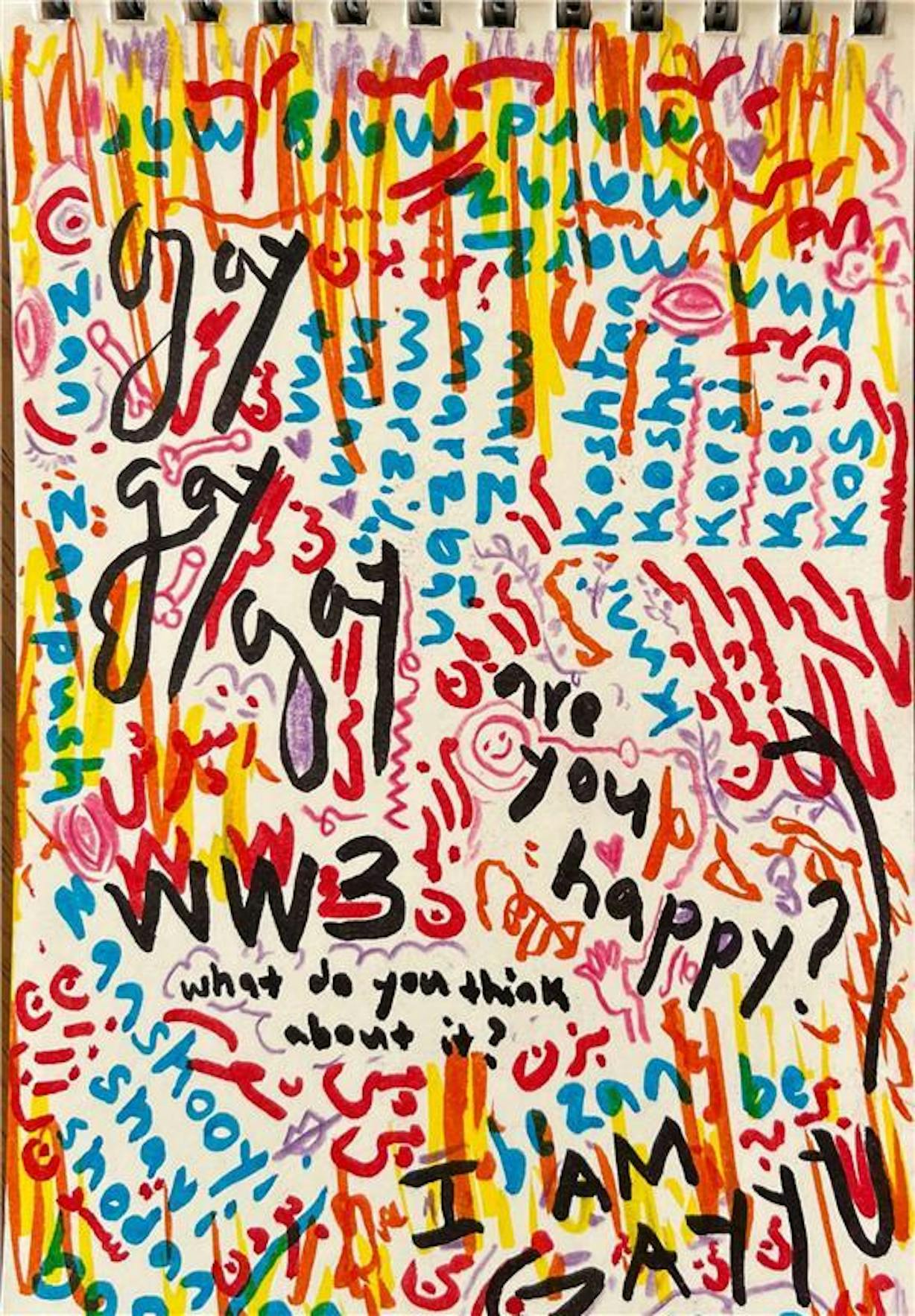

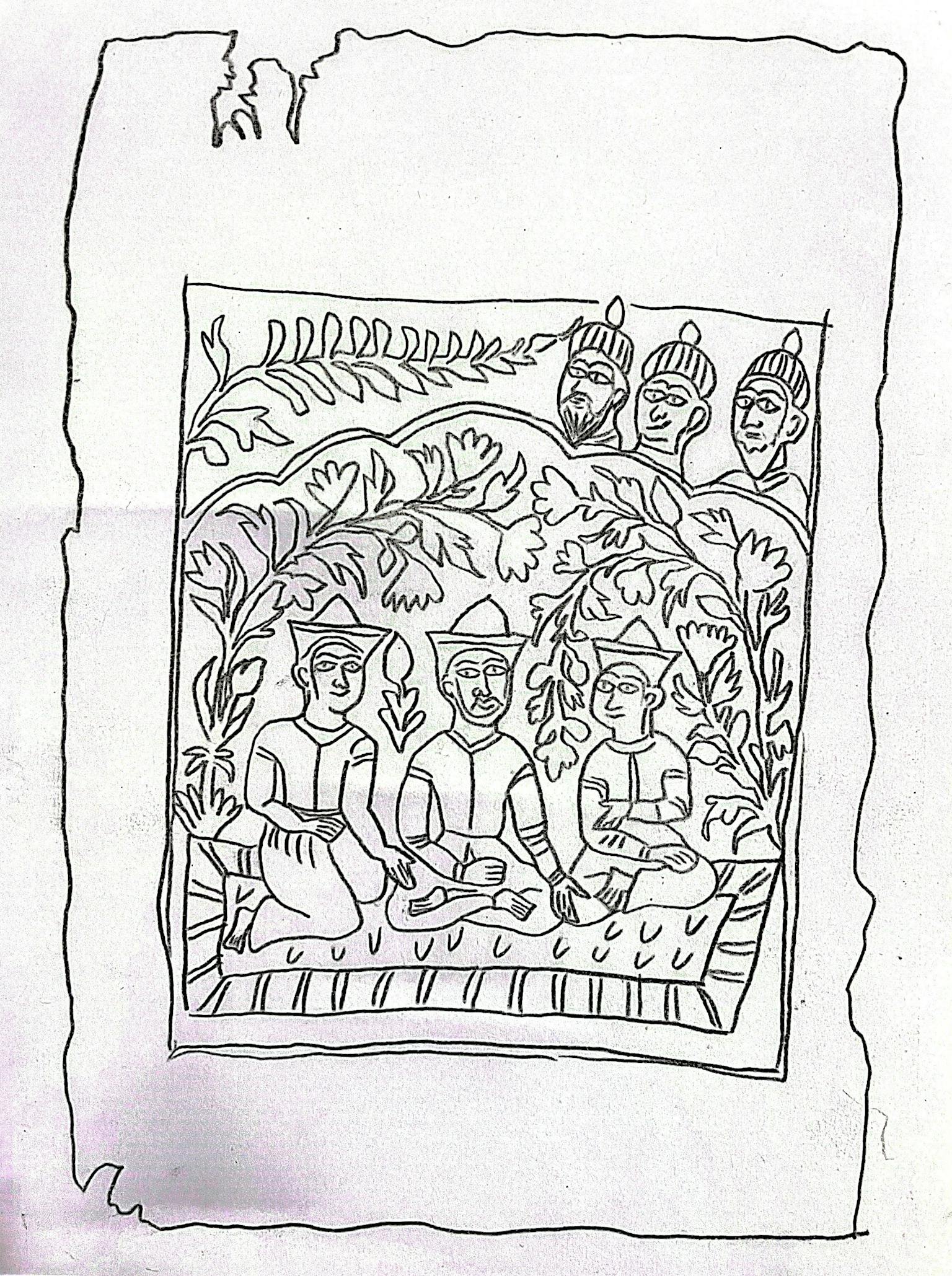

Ashkan Sepahvand, from the diasporic gibberish series (2025), marker and coloured pencil on notebook paper, 105 x 148 mm.

Later, it hit me that ‘gay’ also means ‘happy’. The slipperiness of sense made me uncomfortable. I certainly didn't feel happy; if anything, I was angry and ashamed. I remembered that the statement ‘I AM GAY’ accompanied a pervasive feeling of political lack. Despite its literal connotation of ‘enjoying liberation’, no amount of effusive language could mask the persistence of unfreedom. Rather than having something to say about it, I was articulating both a blockage of speech as well as its possibility within impossibility.

The following week, a heatwave overtook Europe. My libido rerouted itself into a feverish flow of words that I scribbled into a notebook. Though I was no longer seeking out sex, I still yearned for aliveness. Between English and Persian, I translated ‘I AM GAY’ into names for the self and the body. diasporic gibberish, I called it. Each drawing-poem took shape as phonetic associations and cheeky wordplays. For example: ‘marz-maraz-mard-marg-mar’ (meaning border-disease-man-death-snake), or ‘more-many-men-melt-musk-masc-masquerade’. Letters elongated into slithering shapes. Ornament animated the empty spaces with flowers, flames, dragons, and demons. Whatever I was trying to say, it seemed apocalyptic. Maybe that's it: doesn't apocalypse emerge from the sense that nothing can be done?

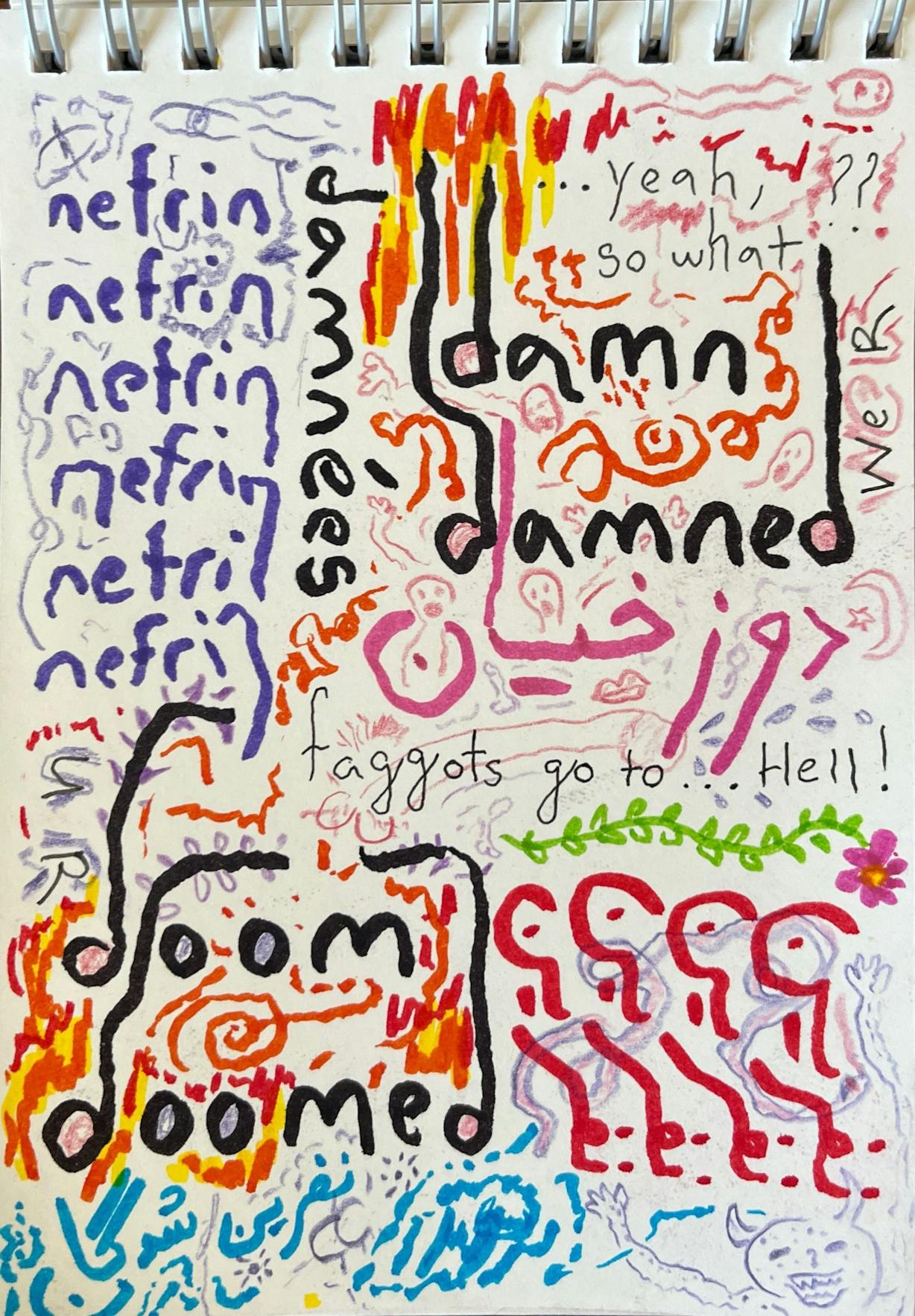

What if ‘I AM GAY’ is a curse? When grasped as an utterance, its words start to sound like a barbarous name. As the speaker’s insistence on meaning withdraws, another sense emerges, attuned to what resonates in-between the spoken: a silent voice crying out ‘damn, damned, doom, doomed’. A curse upon me, you, them – the men, with their always-crumbling Empires and their always-limiting categories of identity. A spell against their so-called civilisation, with its savagery and lies. Could there be an infernal joy in speaking out damnation? Perhaps there is something both ‘gay’ and ‘happy’ in announcing-pronouncing-denouncing a hellish fate. If this all sounds like some kind of black magic, then maybe demons must be fought with demons.

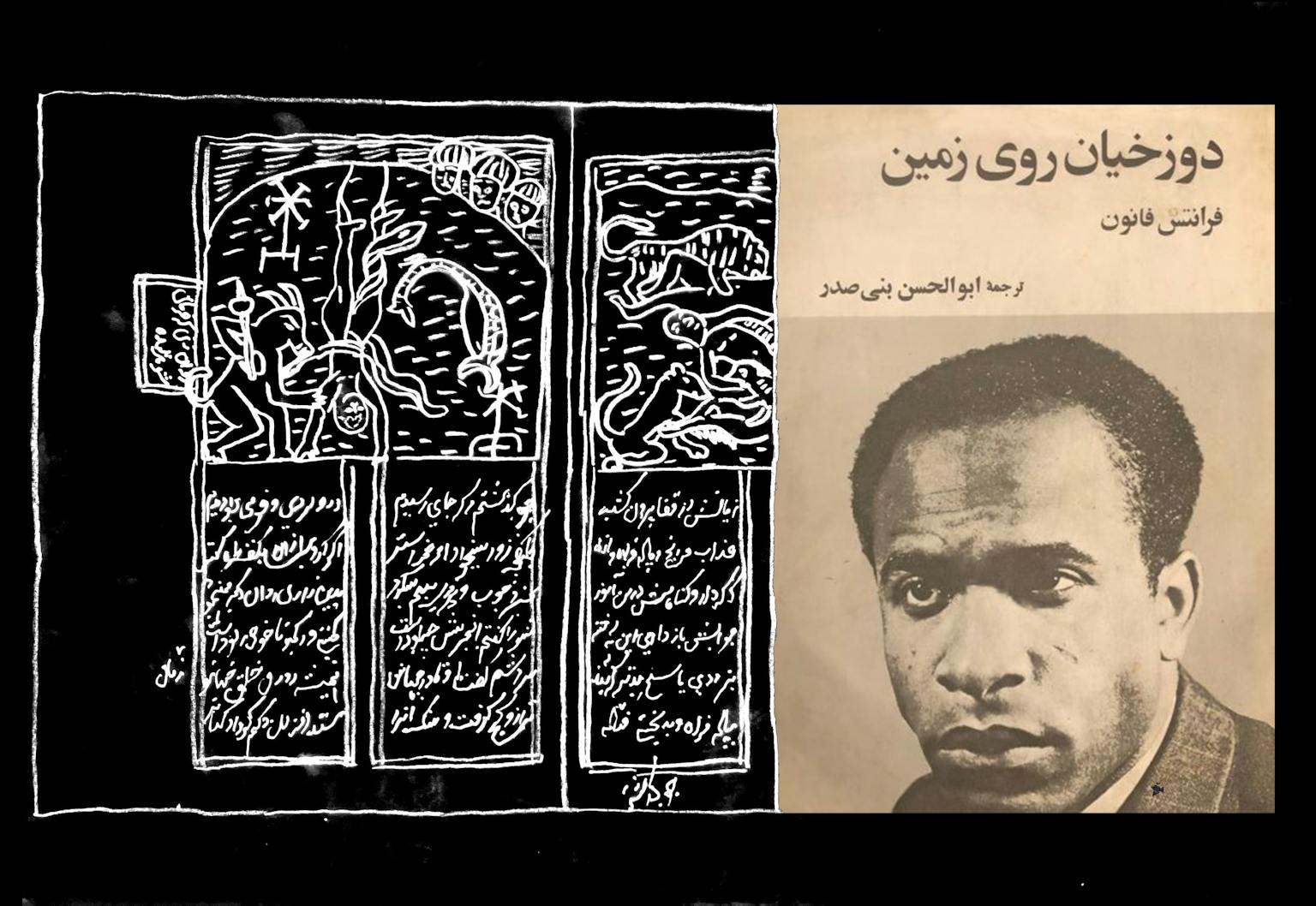

Left: Ashkan Sepahvand, scan inversion of drawing, traced by hand from Ardavirafnameh (1789), Persian MS 41, Rylands Collection, University of Manchester Library.

Right: Cover of the Persian translation of Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, Tehran: Amir Kabir Publishers (1979)

In 1969, the Persian translation of Frantz Fanon's Les damnés de la terre was published by the Mossadegh Press.1 No translator was named in this first edition. Legend associates the work with Ali Shariati, the Islamist-Marxist intellectual and sociologist of religion. Shariati had studied Fanon's work in Paris, met Jean-Paul Sartre, and collaborated with the Algerian National Liberation Front. His own messianic thinking radically fused decolonial critique with Shi'a revolutionary theology.

The historian Eskandar Sadeghi-Boroujerdi has argued that it was, in fact, Abolhassan Banisadr who translated Fanon.2 In support of his argument, Sadeghi-Boroujerdi underscores the discrepancies in word choice from previous, partial translations of The Wretched of the Earth. For example, in his lectures Shariati consistently used ‘maghzoubin’ (those incurring wrath) to render ‘les damnés’. Whereas another anonymous translation (this time of Sartre's preface) in the journal Negin used the word ‘nefrin-shodegan’ (the accursed) instead.3 Much like ‘wretched’ in English, these translations are inexact yet evocative of a condition.

I'm not interested in the question of who translated Fanon. Instead, I want to reflect on the ‘wordliness’ of what was ultimately chosen to convey the title Les damnés de la terre in Persian: Duzakhian rooye zamin.4 ‘Duzakhian’ means ‘the inhabitants of Hell’ or, to coin a neologism, ‘Hellishes’, while ‘rooye zamin’ means ‘on Earth’, suggesting a physical location for the damned rather than an attribution as expressed by ‘of’. Let’s translate the Persian title back into English to hear its effect: Hellishes on Earth. It’s as if a magical re-formulation has occurred. The words summon the presence of apocalyptic beings who are already in the world. In this sense, the choice of duzakhian captures the religious valence of les damné more accurately than ‘wretched’ does in English, a word closer to poverty and misery than divine judgement.

‘Duzakh’, however, is not the go-to word in modern Persian for Hell. ‘Jahanam’ occupies that role, a word that comes from Arabic and is tied to Islamic notions of eschatology and the afterlife. Duzakh is a rare and arcane word, specific in Persian literature to the genre of medieval Zoroastrian apocalypse. In the immediate aftermath of the Sasanian Empire’s fall in the mid 7th century, the endangered Zoroastrian priestly class compiled recensions of oral tradition in an effort to preserve their religious knowledge.5 Texts such as the 10th-century Denkard (Acts of Religion) or the 9th-century Dadestan-e-Denig (Religious Judgements) are marked by a fear of contagion and contamination. Exhibiting a post-Conquest symptomatology, the dangers of sin, pollution, demons, and Hell are foregrounded in these works. They display a reactionary, xenophobic paranoia that associates the arrival of Muslim Arabs with the demonic forces of Ahriman, the Evil Spirit in Zoroastrian cosmology, as that which ultimately threatens the ‘Iranian people’ with moral, political, and spiritual ruination. 6

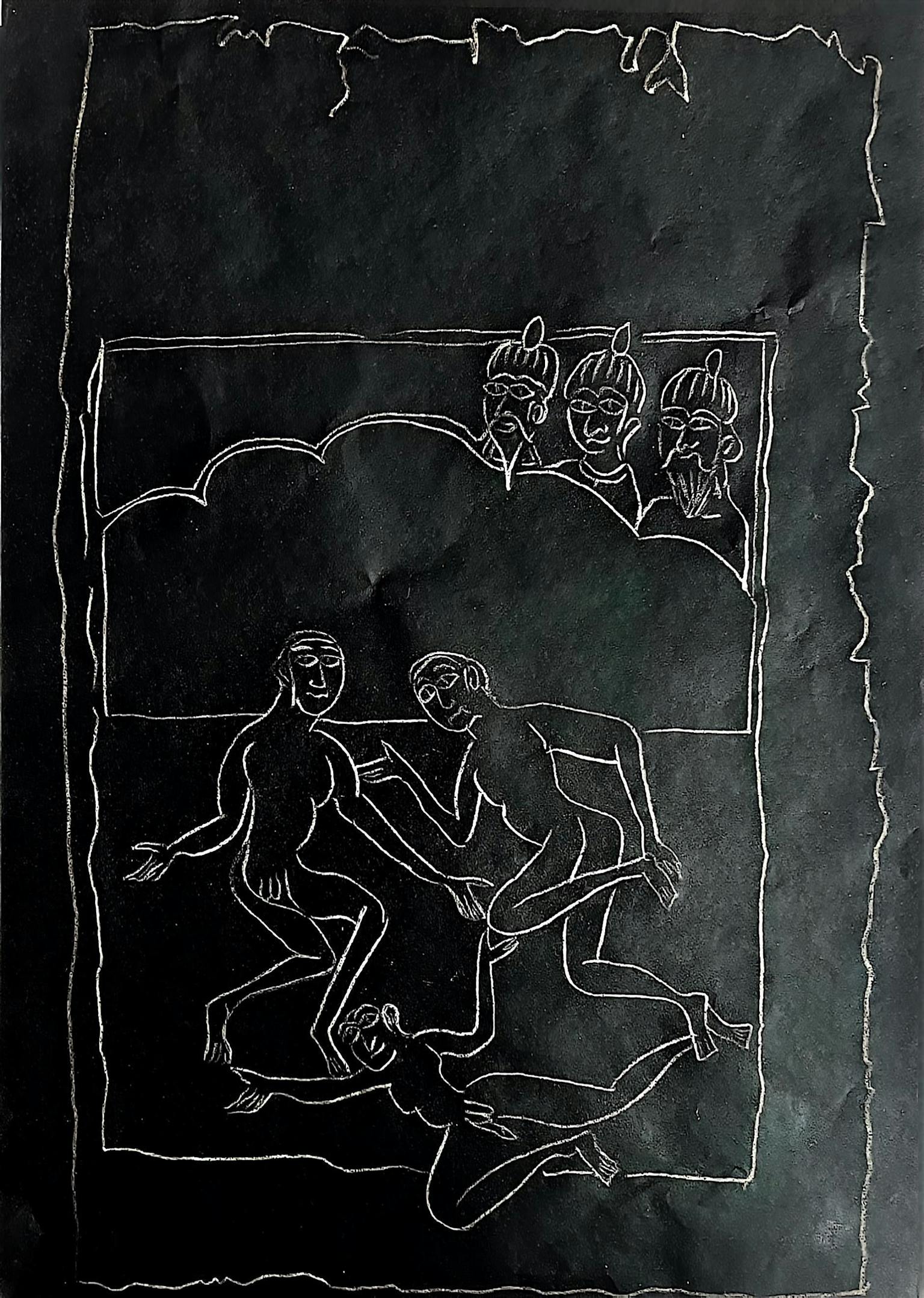

Ashkan Sepahvand, frontispiece to Heaven, scan of carbon transfer onto paper, traced by hand, from Ardavirafnameh (1590), Islamic Manuscripts, New series, no. 1744, Princeton University Library

Nowhere else in the Zoroastrian corpus, however, is more attention paid to the description of Hell and its inhabitants than in the Ardavirafnameh (Book of Arda Viraf). Scholars agree that the current recension dates to the 9th and 10th centuries while drawing on older, pre-Islamic traditions.7 Neither a theological nor legal text, the Ardavirafnameh falls into the ‘visionary genre’ of apocalyptic literature.8 With astonishing similarities to the narrative of the Prophet Muhammad's Miraj (Ascension) and Dante’s Divine Comedy, the Ardavirafnameh is, essentially, a tour of Heaven and Hell.

Set in a time of religious calamity and cultural confusion caused by Alexander the Great's conquest of Iran, a ‘righteous man’ (literally, ‘Arda Viraf’) is chosen to journey to the otherworld and bring back testimony to fortify his community’s faltering faith. To be expected, Heaven serves to justify the symbolic order of the ancien régime: its inhabitants are landowners, taxpayers, productive farmers, docile slaves, and obedient, childbearing wives. As always, Hell is where things get interesting.

Fanon’s translator may or may not have been aware of this literary dérive. This doesn’t concern my argument. Instead, I’d like us to focus on what the word ‘duzakhian’ does and the implications it has for translating a certain politics. Fanon’s Les damnés de la terre is profoundly informed by psychoanalysis, Marxism, and the Algerian War. It elaborates on the deformations of spirit and body caused by Empire, reflects on the plight of both coloniser and colonised, and develops an urgent, if often misunderstood, theory of political violence. With what imaginary is Duzakhian rooye zamin able to hold Fanon's decolonial vision?

In the Ardavirafnameh, the duzakhian are beings who have been condemned for their excessive embodiment. They are unruly women and unmanly men. The text expresses hatred towards chaos, corporeality, and femininity. Its fantasies of punishment present obsessive fixations on the most intimate areas of the sexed body, articulating an inhuman primal scene in which noxious creatures – ‘xrafstar’ – torture, molest, rape, devour, and disfigure the Hellishes. The specific part of the body that commits sin while alive becomes the inverted locus and logic of hellish punishment: suck a dick / choke on a dick; talk shit / eat shit, and so forth.9

Ashkan Sepahvand, frontispiece to Hell, drawing on carbon paper, traced by hand from Ardavirafnameh (1590), Islamic Manuscripts, New Series, no. 1744, Princeton University Library

The entrance to Hell is guarded by a ‘profligate woman, naked, decayed, gaping, bandy-legged, lean-hipped, and unlimitedly spotted’, representing the collective sum of humanity’s bad deeds.10 The first duzakhian encountered are the sodomites (‘kunmarz’), whose punishment is some weirdly arousing, eternal spit-roast.11 Serpents enter their bodies via the mouth and exit via the anus, only to loop back around again in a perpetual, dildotectonic circuit – an infernal Ouroboros-turned-monstercock.12

This is followed by a listing of bodies that threaten pollution: menstruating women, those whose touch is improper, or who mishandle the elements. There are those deemed non-productive, the lazy and the vagrant, the refuseniks, evaders, and bandits. There are the pleasure-seekers whose pursuits offend patriarchal law and order. There are those whose ‘tongues are sharp’, disobeying their masters and husbands. Those who resist, revolt, and rebel against worldly rulers and their armies find themselves closest to Ahriman himself. Revolutionary desire is damning.

The spatial structure of Hell does not seem to have any immoral hierarchy, as is the case in Dante's Inferno. The sins of the duzakhian appear equally ‘margarzan’ (‘worthy of death’) and are randomly distributed within the text’s perverse psychosexual wasteland.13 This would suggest that each recension allowed for an author to add, revise, and modify who and what should be considered Hellish. The criteria remain consistent: anarchy is reviled, ungovernability shall not be tolerated, eroticism is horrifying. As such, the classical category of duzakhian indexes the vicissitudes of masculine power and its monopoly on violence. Its textual elaboration records and registers Empire’s moving targets, as well as the mutability of what the men consider a threat to their chokehold on the symbolic.

This foray into Zoroastrian arcana does not aim to valorise some uniquely Iranian metaphor. It is the incongruity of meaning between Persian and French or English that is at stake in the wordly. An analogy from Walter Benjamin's 1923 essay ‘The Task of the Translator’ comes to mind: though the French ‘pain’ and the German ‘Brot’ both mean ‘bread’, their sonorous difference points to something mysterious lingering in-between, beyond communication. In their interlingual babble, there is the unspeakable trace of a divine language forever lost to living speech.14 Put differently, the literature of duzakhian interjects into the name of Les damnés the potential history of unspoken forms-of-life, held together by the signifier ‘revolution’.

The duzakhian of the Ardavirafnameh are a fantasy of disavowed aliveness. They are beings that are too bodily, too desiring, too much, so much so that they must be displaced elsewhere. The men of this world have condemned them to the realm of the dead, where it is hoped they shall suffer in silence, invisibility, and oblivion. The Duzakhian of Fanon in Persian are, however, Hellishes on this Earth, are revenants from a Hell that questions the spatio-temporality of Hell altogether. Because what is Hell if not all the territories – this world, this life, this body – that Empire seeks to ruin?

Hell is political. By translating Fanon’s Les damnés as Duzakhian, the lumpenproletariat become libidinally charged: sodomites, whores, vagabonds, anarchists, terrorists, the so-called ‘faggots and their friends’15 all join their chaotic ranks. Imperial discourse displays significant continuity between religious-legalistic antiquity and scientific-humanitarian modernity. Sodomy and feminine desire as ‘sin’ turn into homosexuality and hysteria as ‘pathology’. The affective residue of this long violence remains impactful: shame can’t just be Pride-paraded away.

Hell is psychic. Much has recently been written about Fanon’s practice as a clinician.16 Les damnés de la terre is propelled by Fanon’s case studies, his professional observations on the trauma, hurt, and suffering coloniality inflicts upon the spirit and inscribes upon the flesh of its subjects. Reactionary psychoses, racialised and sexualised, haunt all those subjected to Empire’s repression. Nightmarish visions, manic eruptions, violent outbursts, destructive drives, and unhinged libidos – a hellish unconscious – are symptomatic consequences of earthly damnation. If Heaven isn’t the cure, then maybe Hell holds the answer.

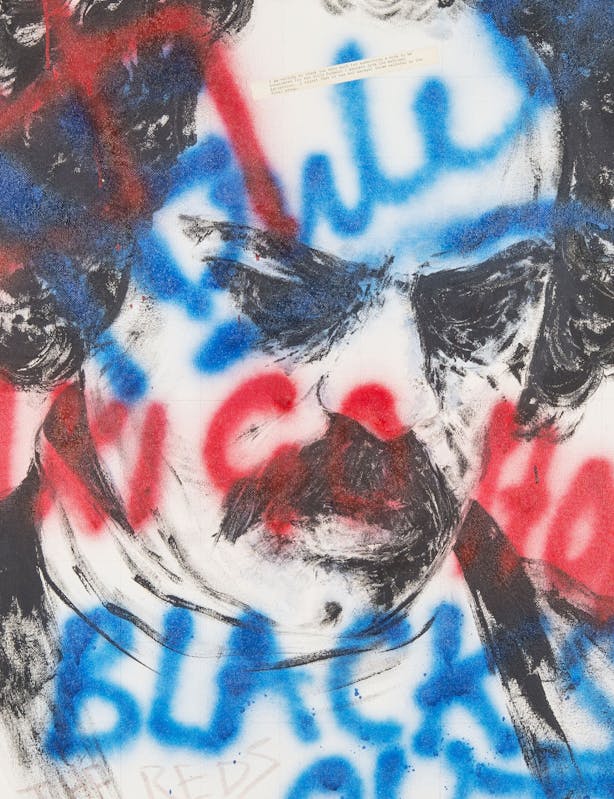

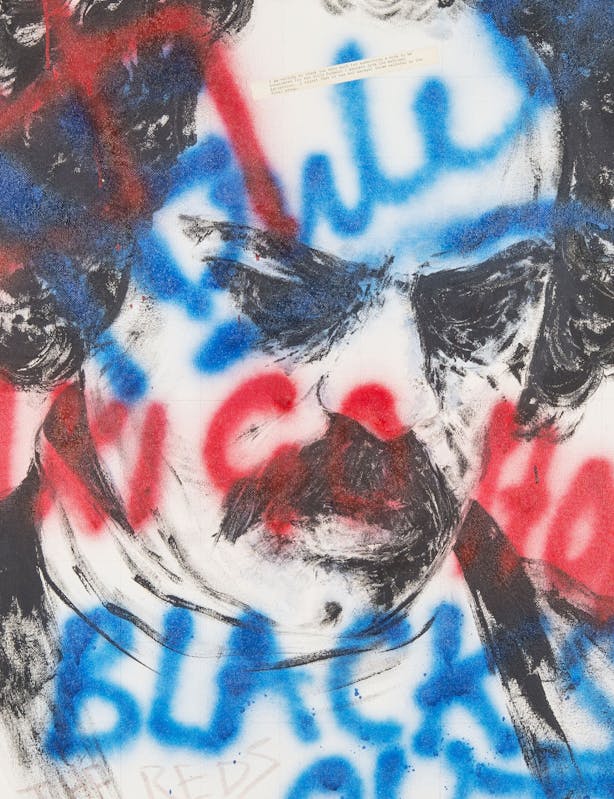

Ashkan Sepahvand, Untitled (the demon of history) (2025), scan inversion of drawing

The literary interface between Duzakhian and Les damnés exposes the persistence of what queer theorist Heather Love calls ‘backward feelings’. For Empire’s flagship project of modernity, elaborate technologies have been developed to name, condemn, and capture those deemed backwards while making sure the so-called barbarians never catch up: sexual and gender deviants, women, non-whites, the colonised, the poor, the criminal. Discourses of progress, inclusion, and human rights have been articulated as a conceptual antidote to Empire’s violence, proclaiming triumph over the broken past. Yet brokenness keeps interrupting the present.17

‘Sometimes damage is just damage’, writes Love.18 Indeed, for ‘groups constituted by historical injury’,19 we have known this bitter truth in our bones all along, even if we don’t, won’t, or can’t say it. A mysterious pain lingers under the skin, shapes our desires, interrupts our memories. Sometimes it’s based on actual experiences we would rather forget; other times it feels like it’s been transmitted across unknown lives and distant worlds. Occasionally a disturbing thought flashes up, barely there, too shattering to consider: what if they really want us dead?

When I read about duzakhian, a part of me I wish to ignore feels shame, anger, sadness, and frustration. There’s the uncomfortable reminder that living homosexual desire carries the residue of antagonism. At the same time, I am repulsed by the imagination of a culture capable of fantasising such monstrosities. Yet, as Love reminds us, ‘turning away from past degradation to a present or future affirmation means ignoring the past as past; it also makes it harder to see the persistence of the past in the present’.20 By re-inviting duzakhian to haunt the here and now of translation with their backwardness, Fanon’s project of ‘national culture’ is infused with the affective potential of the demonic.21 The revolutionary praxis of creating an other culture after Empire must not fall into the trap of fixing, editing, and revising history’s losses. The dead cannot be normalised as angels.

Any decolonial struggle will have to take on the disturbance of anachronisms that act as a drag on the present, damning its progressive narratives of redemption. Sylvia Wynter puts this historiographic sentiment beautifully in conversation with David Scott: ‘I wanted us to assume our past: slaves, slave masters and all. And then, reconceptualize that past.’22

The word duzakhian translates out of les damnés the fullness of a troubling lineage. Assuming its name allows for a transformative re-living of damnation as an earthly burden. Its backward imaginary is capable of surviving ‘through the furnace of the past’.23 The Persian word enriches Fanon’s discourse with a revolutionary corpo-reality intensified by bad attachments. Importantly, it re-energises the political and psychological consequences of Empire’s damning alienation. By moving ‘away from identification and toward desire’, speaking ‘duzakhian’ activates the secret power of the curse.24 Rather than being subjected to a condemned identity, condemnation becomes the object of hellish longing: our damnation is your doom.

Ashkan Sepahvand, from the exquisite corpse series (2025), oil pastel on black card paper, front, 148 x 210 mm

I've recently been playing Exquisite Corpse – the Surrealist game, originally done with words but also with images. In the latter case, a piece of paper is folded into three sections representing a body: a part for the head, another for the torso, the last for the legs. When played with others, each takes a turn drawing one section. It’s a way to give up control over the final composition of the image. The paper is then unfolded to reveal a strange assemblage, a body whose appearance doesn’t make any sense. Much like death, whose truth is non-sense.

I don’t have anyone to play with, so I’ve been drawing my corpses alone. It’s surprisingly effective. Hiding the full page from view disturbs the imagination, trips up memory, and scrambles the desire for wholeness. I use colourful oil pastels on heavy black paper. I work quickly, with intuitive, expressive strokes. I don’t use any fixative. As I move on to the next folded section, the pastels smear and fleck. The body is messy. The image is tenuous. Touching it risks spreading pollution, ruining it. Though it’s called a corpse, there are marks of aliveness.

I imagine the Hellishes. The colourful, frenetic lines on black paper draw out of Hell’s dark oblivion ‘forms of chaos that can never be conquered’.25 I am gay, so I illustrate kunmarz and its – my? – diabolical fate. The serpent’s cyclical penetration transgresses the boundaries of the sodomite body, collapsing the distinction between inside and out. I re-imagine the threefold divisions of the exquisite corpse as mouth/gut/anus. A creature takes shape along a soft spine, much like the primitive streak of vertebrate embryos. Corporeality organises its complex structure around this initial, undifferentiated axis. Is kunmarz being undone by the serpent, or is it being reborn? As in life, horror exists alongside beauty.

The assault on Iran has passed for now but Empire’s wars continue indefinitely. The men who rule do not seek a true victory. Instead, they measure their success in the maintenance of perpetual chaos. They really do want us dead.

In his preface to Les damnés de la terre, Sartre uses a curious example to interpret the revival of myth and ritual amongst the colonised:

They dance. That keeps them occupied; it relaxes their painfully contracted muscles, and what’s more, the dance secretly mimes, often unbeknownst to them, the NO they dare not voice, the murders they dare not commit.26

The passage rightfully suggests that the body says it all, even when words say something else altogether. But I disagree with Sartre’s interpretation that this unspoken message is a NO. Staying with the text’s example, would the ‘amused gaze of the colonist’ not consider such a dance backward and barbarian?

There is another form of resistance far more powerful, fearful, and dangerous than the exhaustion of constant refutation. In her 2022 book In Defence of Barbarism: Non-Whites Against the Empire, which is greatly informed by Fanon, the journalist Louisa Yousfi writes: ‘If you needed to sum it up in a slogan, it would be: Yes, so...?27 This is another magic formula: Barbarian, yes, so...?’ She continues: ‘Barbarians are products of this civilisation but not reducible to it. Their existence testifies to an unplanned mutation that is not encoded in the civilising process. One might even say that they are ahead of civilisation.’28

The last thing the men who rule Empire expect is for the barbarian to accept its condemnation. Re-reading Sartre’s anecdote, could the dancers’ grasp of lack expose the philosopher’s lack of grasp? Rather than the panicked, liberal charade rushing to justify itself with excuses or equivocations – ‘No, but we are human, too!’ – the ecstatic thrill of hellish bodies in motion affirms everything Empire suspects about its monstrous others:

YES, so...? We are the Hellishes and we want the men dead!

Let’s not forget that we are dealing with magic here. Words are not what they appear. The power of the curse isn’t literal, it’s mysterious. ‘Yes, so…?’ isn’t a silly endorsement, it’s serious fun, a counter-spell for those in the know. Yousfi admits this formula is bound to be misunderstood: ‘It’s at once sad and fascinating to observe the obsessive scrutiny of any sign that might remotely hint at a desire for vengeance.’29 And why shouldn’t there be any? Much like the rage implied between the question ‘Are you happy?’ and the response ‘I AM GAY’, the art of antagonism is at play in this uncanny game of affirmation.

For the Hellishes, the muscular outbursts and libidinal disturbances that mobilise our aliveness bear witness to ‘the wasteland in us,’ an inner ruin that prevents our ‘integration’ into Empire.30 It is what pulls our souls back from cultural disappearance. This has nothing to do with rediscovering what’s been lost, and everything to do ‘with resisting what we are in the process of becoming’.31 The demons of our past are time-travellers from the imperial present, orchestrating an apocalyptic future. To be Hellish means to turn backward to get ahead. If we are duzakhian, then maybe Ahriman – literally, the ‘Angry Mind’ – is our God after all. Some angers are worth praising.

Qalandar Bux Memon

Basma al-Sharif, Sophia Al Maria, Lawrence Lek

Stephanie Bailey, Radha D’Souza, Adam Broomberg, Françoise Vergès, Anjalika Sagar, Nour Yakoub, Gaurav Sinha