- Mission Statement

3. Who Are Our Audiences, Users, Protagonists?

Jonas Staal, Nadja Argyropoulou, Basma al-Sharif

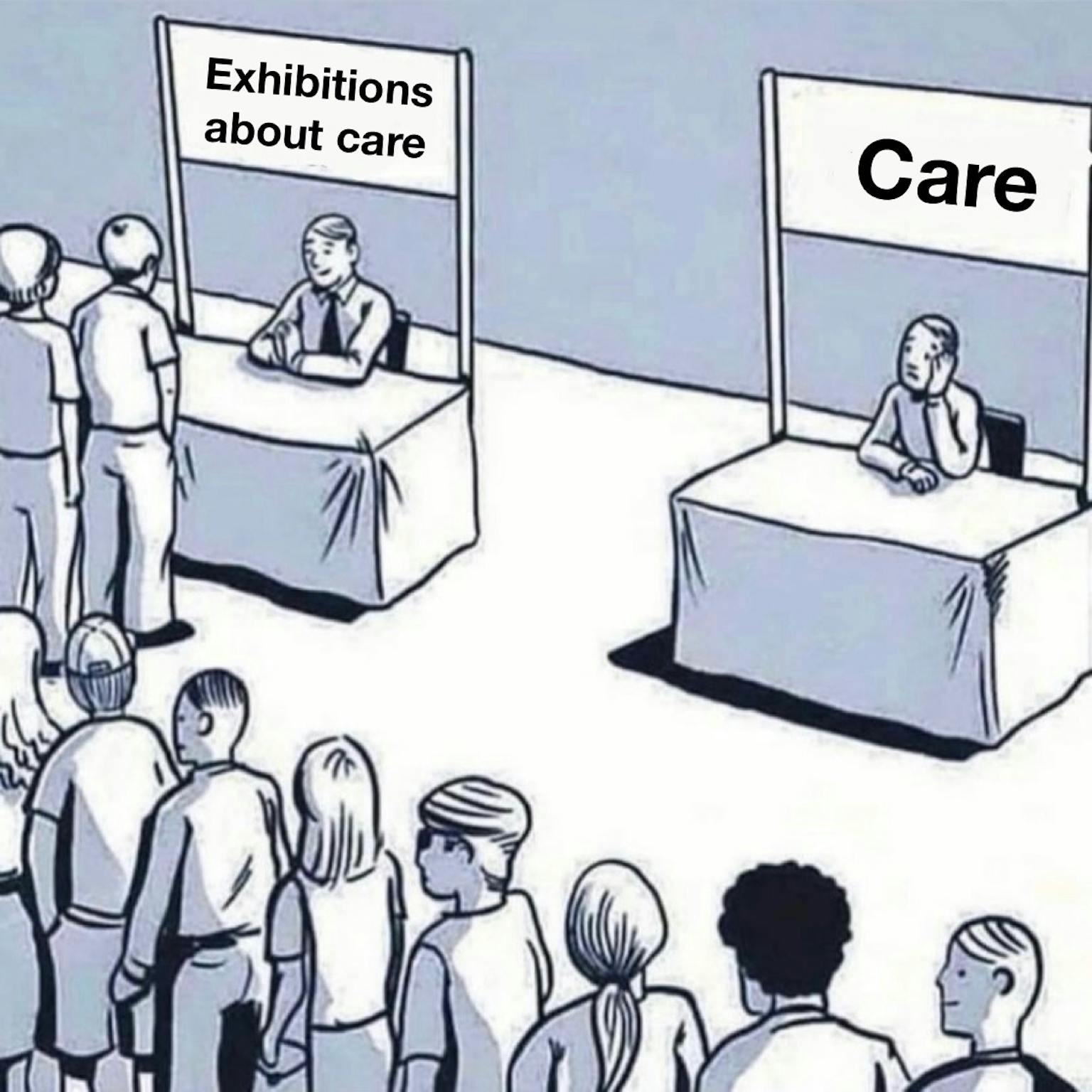

Cem A. diagnoses the current institutional climate of soft moral alignment, where art gestures toward politics without the difficulty of being political, and proposes strategic empathy as a potential path out.

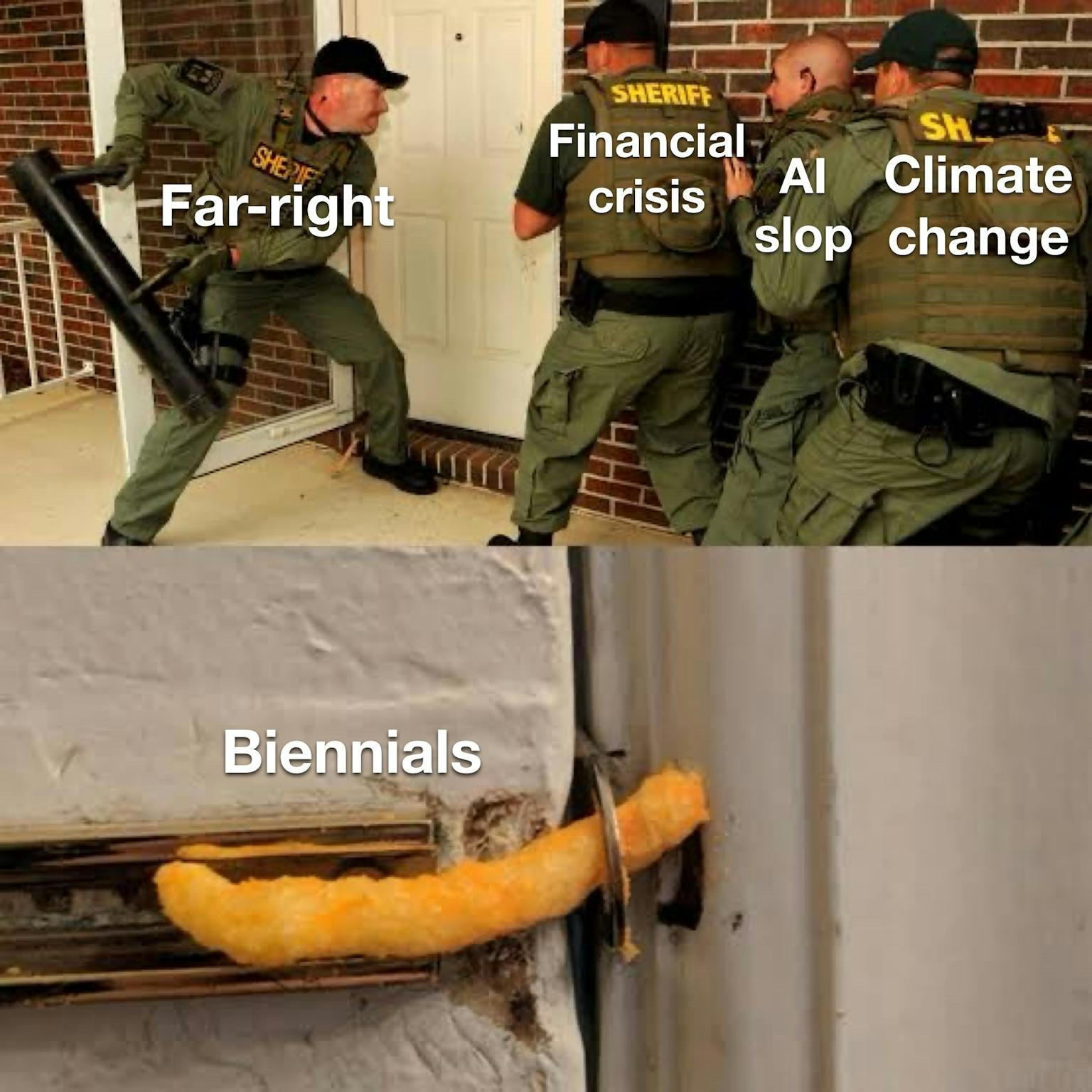

We live in a moment when the existing world order – political, ecological, and economic – is visibly collapsing. The Earth has already breached seven of nine planetary boundaries, global wealth inequality has reached historic highs, the authority of international organisations such as the UN is under threat, and even their designation of what has been happening in Gaza as a genocide has become a matter of dispute. The status quo upon which the political efficacy of art was once premised is eroding, yet exhibitions continue to carry the same curatorial reflexes that flattens politics into overly simplified symbolic gestures that circulate well, and mean increasingly less. I call this institutional code for agreeability ‘Consensus Aesthetics’, not because everyone agrees, but because disagreement has become harder to voice.

Consensus Aesthetics isn’t a style so much as a climate: an atmosphere of aestheticised values, soft moral alignment, and benign radicalism that is expressed mainly through institutional programming across the art world’s global mainstream. It’s art that looks right, sounds right, aligns with institutional values, and circulates easily, gesturing toward politics without the difficulty of being political.1 It flourishes under certain material conditions – global funding bodies, institutional precarity, liberal internationalism – and flatters progressive ideals while remaining structurally conservative.2

Consensus Aesthetics blocks the possibility of a discussion with real consequences and avoids contradiction, because genuine criticism carries political cost and any tension generates bad optics. Institutions that toe this lowest common denominator thematic line don’t confront the present; they perform around it, with familiar acts that are becoming harder to digest as if curated in a parallel timeline where the current crises never occurred. Without engaging with complexity or facing contradiction, politics slides into branding and art into a loop of moral cues: care, solidarity, decolonisation, ecology, crisis.

Courtesy of Cem A.

A flurry of recently published writing all point to a growing discomfort with the consensus-driven tone of contemporary art and its institutions. Eddy Frankel’s piece on trauma and politics, questions whether the dominance of pain and trauma as curatorial themes has constrained critical engagement; whether the spectacle of suffering has made it harder to speak plainly or disagree publicly.3 Rosanna McLaughlin’s Against Morality (2025) critiques the instrumentalisation of moralism in art, where work is often praised for its alignment with ethical virtue rather than its formal or conceptual rigour.4 Rahel Aima’s ‘vaporwave’ curating describes a new mode of exhibition-making: nostalgic, smooth, emotionally soothing, and politically ambiguous.5

There was a time, not so long ago, when the art world seemed to believe that art wasn’t just political, but politically powerful; that through symbolism, form, or moral righteousness, art could challenge systems, shift public discourse, even destabilise the status quo. Maybe that belief was always more aspirational than accurate. Whatever it was, that era is over – but its forms remain. Major or minor, institutions still cling to the idea that aesthetic gestures carry political weight: programming continues to mistake representation for transformation, and everyone is expected to affirm the charade.

Perhaps ‘International Art English’ was an early warning sign — a language that mimicked academic language while hollowing out its rigour.6 We’ve been here before, but now, something feels more entrenched.

Consensus Aesthetics operates on multiple, mutually reinforcing levels. First, there is the aesthetic level: the sense of walking into a show where urgency itself feels worn out, as if already circulated years before. Urgency has become its own style and artists have learned to speak in a repertoire that signals immediacy, relevance, and gravity: archival footage, found objects, care-as-theme, community as format. Rather than reward the real slow, unglamorous, and often invisible labour of community-building and political activism, institutions seem to reward the appearance of them instead, deeming it urgent, relevant, and in return ‘important’. The effect is an aesthetic of political simulation. A work might appear political without exerting political influence: a simulation that is often secured by attaching the artist’s identity as guarantor, as if the moral weight of who they are is enough to validate the political claims of the work. What seems political is easier to exhibit than what attempts to be political: we confuse politically coded art with politically impactful art. But legibility is not the same as consequence and moral positioning is not the same as political force.

Courtesy of Cem A.

The second level of Consensus Aesthetics is the interpersonal: in a climate of institutional precarity, everyone becomes fluent in the soft choreography of non-confrontation. The safest move is to nod, give a harmless compliment, and gesture toward critique without expressing any. It’s not just self-censorship but survival. No one wants to risk future work by being difficult or unpredictable. Over time, this cultivates a language of agreement that becomes second nature, even when disagreement simmers beneath the surface. Consensus arises less from alignment than from the suppression of what cannot be said.7

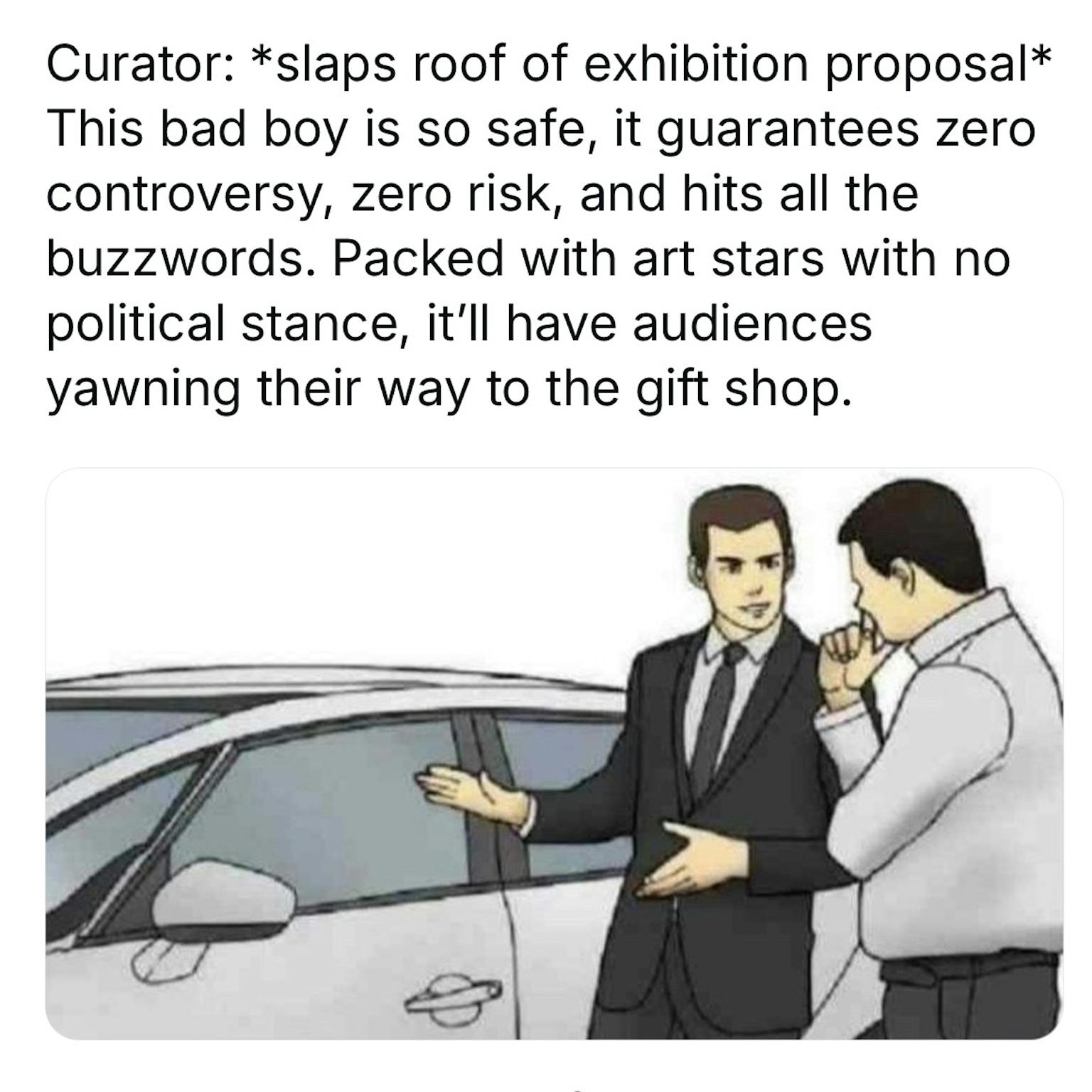

The third level of Consensus Aesthetics is infrastructural. Behind all these signs and gestures lies the machinery: governmental funding bodies, private patrons, murky non-profits, grant applications, communication strategies, and the quiet diplomacy of the international art circuit. The result is a curatorial loop of strategic smoothness, because conflict is bad for funding. Artists pre-edit their intentions; curators look for works that won’t collapse under institutional scrutiny; administrators must answer upward – balancing politicians on one side and donors on the other – making the institution’s survival dependent on conflict-avoidance. When everyone’s trying to stay employed, disagreement becomes a performance of agreeability maintained through ambiguity, politeness, and quietness.

Courtesy of Cem A.

While this condition seems to define the zeitgeist, Consensus Aesthetics predates the contemporary moment. It is visible in the very structure of the western art canon and an art world that has been historically shaped by a narrow, overwhelmingly western perspective that filters, preserves, and ‘normalises’ certain practices into legible categories. The museum’s role has long been to transform the chaotic matter of global artistic production (a disorganised, uneven, contradictory field) into a uniform mass through selection, and this process is neither neutral nor incidental. While some works are elevated into visibility, countless others are quietly forgotten.

While the slow inclusion of marginalised voices into the institutional mainstream is often framed as progress, the pace is glacial and the inclusion is always partial. It operates at the level of collective memory and collective amnesia with tremendous resistance to change once something is canonised. Archiving can be a tool of exclusion as well as preservation, and the omissions often start with geography. The so-called Global Majority is historically kept outside this silo, recalling Stuart Hall’s text ‘The West and the Rest’, which argued that the West has never been a fixed identity with stable boundaries, but rather defines itself by observing what lies outside and naming what it is not.8 What counts as art is less an archive of what has happened than a framework reinforced through institutional choice, reflecting a deeper logic of the minority defining the majority.

The climate protests of recent years have made this contradiction abundantly clear. The same institutions that celebrate artists destroying things in the name of form, have responded with moral panic and increased security, policing visitors to prevent activists using exhibitions to stage symbolic interventions, even when no damage was done.9 The irony is that climate catastrophe, and the call to preserve the very conditions of life, is arguably the least divisive cause: something that anyone should be able to get behind, even if only performatively. Yet for some institutions, activism about climate crosses a line. Not because of destructive acts, since protesters don’t actually destroy anything, but because protests create real conflict. Museums are wired to host consensus, not disruption, and arts professionals, knowingly or not, are gatekeepers of this tendency. In this sense, Consensus Aesthetics is protective of its own stability, continuity, legibility. But what is being protected from whom and for whom?

Courtesy of Cem A.

There is a clarity to that question when you look at the art market, which operates within the gravitational pull of consensus to maintain value and does not hide that fact. Aesthetics must be familiar, and the language must be diplomatic, because the illusion of neutrality serves the structure. Buy under consensus, sell above it. Acquire the undervalued name just before it gains institutional approval. It’s a form of calibration, and actors within the marketplace try to game this process rather than reject it. Public collections anchor private markets – what’s collected in a museum today determines what’s traded at a fair tomorrow – and vice versa.10 Consensus doesn’t break – it self-corrects. What’s considered ‘digestible’ travels further and faster through this network, carried by the soft influence of social and financial capital, where overt attempts to manipulate consensus risk backfiring.11 Art fairs make this abundantly clear, which contrasts with the moral dilemma of biennials that try to please everyone and end up pleasing no one.

But the application of Consensus Aesthetics holds across all these spheres. Take museums, which absorb works into public collections not to resell them, but to hold them. Deaccessioning is rare and controversial by design. This resistance to financial liquidation creates a buffer zone: a shield that preserves not just objects, but the financial architecture of consensus around them. The overall ecology depends on a long-term belief that the consensus will hold. In this sense, Consensus Aesthetics, which could be understood as the mainstream art world’s socioeconomic contract, functions protectively of its inner logic. This protective dimension of Consesus Aesthetics brings to mind what Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò calls ‘elite capture’, which describes what happens when some actors benefit disproportionately from any value system, whose rules (whether by design or by accident) end up favouring certain individuals or groups, who in turn consolidate their advantage.12 Consensus Aesthetics is no exception. It is consistently steered by those best positioned to navigate and profit from its codes. So what tactical tools remain for the non-elite?

Right now, Consensus Aesthetics appears to be safeguarding what too often resembles a kind of cultural monoculture, dressed in the vocabulary of inclusion. Yet, as demonstrated in the 1950s, when a U.S. Air Force researcher measured over 4,000 pilots to define the ‘average’ body across ten dimensions, there is no such thing as one single fit.13 Even when comparing just three traits, such as neck, thigh, and wrist size, fewer than 3.5 percent of pilots matched, leading to a clear conclusion: designing for the average means designing for no one. I think about that when I see exhibitions shaped by Consensus Aesthetics. So many works aim to balance ethics, form, and legibility. But that balance, like the average pilot, doesn’t exist.

I want to underline that I am not anti-institution, nor am I approaching the condition of Consensus Aesthetics from a purely moralistic point of view. Institutions can and should serve protective functions for individuals, communities, and vulnerable practices that need time and support to grow. But that protection must be extended to more generously reflect what the mainstream often leaves out from its spaces: criticism and disagreement that already exists. In this sense, Consensus Aesthetics shouldn’t be mistaken for consensus itself. Some provisional form of agreement as a shared ground for organising communities and resources is necessary. The point is that this ground should be openly negotiated and revisable, not staged as harmony. In other words, the problem is not that consensus exists, but that it is too often performed as if no conflict exists.

Consensus is a social and political construct, made real by convention and collective agreement. It is, therefore, not a fiction to abolish, but a terrain to fight on. Certain strands of liberal politics in recent years have sought to overwhelm mainstream consensus to suspend it altogether and force change. The task is not to apologise for consensus, but to build political consent around alternative principles and values with new strategies, and to renegotiate these when their time has passed, without delay, while ensuring that one’s stance remains in solidarity with the non-elite.

The question is what kind of consensus we build: one that suppresses conflict in order to appear stable, or one that can absorb conflict without shutting it down. What is needed is not the destruction of institutions, but the development of more porous and courageous ones: a rethinking of the canon not as a fixed vault but as a living field. Picture the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, which was built to withstand catastrophe and safeguard seeds for a distant future. While the vault isn’t failing, the conditions around it – the permafrost that encases the structure – are shifting faster than predicted.14 The predicament of Consensus Aesthetics is not dissimilar: the structure is holding, but the ground is moving.

There’s a saying in management theory: when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. That’s what’s happened when the aesthetics of politics became the target of Consensus Aesthetics – the political potential of art inevitably faded from the art world’s mainstream. So, what is to be done? Is politically coded art to be abandoned altogether, in the face of an overwhelming aesthetics defined by consensus? If consensus is to be meaningful, at a time when public discourse veers into open reactionary politics and the art world retreats into risk aversion, it needs to be built through complex and conflicting discussions that do not insulate institutions from unpredictable, and potentially intolerable, discussions.

Here I want to assert ‘strategic empathy’ as the deliberate, pragmatic act of engaging with different or even opposing perspectives. Not out of moral alignment or emotional identification, but because dialogue, coexistence, and structural change require it. Consensus Aesthetics doesn’t arise from genuine alignment, after all, but from the suppression of what can’t be said. In that sense, the task is less about inventing something new than about changing the codes – to normalise disagreement instead of treating it as a failure to hide.

Unlike conventional empathy, strategic empathy does not seek agreement or validation but rather accepts conflict as a condition of the work, which requires sincerity. Art professionals could learn from anthropology’s use of reflexivity, where practitioners account for their own position rather than claim neutrality – say what the show is for, acknowledge its limits, name their biases. The future lies in exhibitions that don’t pretend that everyone agrees, which admit to being partial and uncertain, and invest as much in mediation as in production. This may sound unfashionable in a field still enamoured with individual expression and moral posturing, but that is precisely what gives strategic empathy radical potential. It challenges institutions and individuals alike to confront perspectives genuinely different from their own, turning exhibitions from sterile zones of neutrality into contested, living dialogues.15

What matters is creating conditions where multiple battles can be named, held, and disagreed upon, and where the moralism that dominates critical discourse can be challenged. After all, to withhold empathy from those you disagree with is still a form of moral evasion that replaces understanding with judgment. This is not a call to uncritically platform reactionary voices in the name of ‘balance’ – that would be complicity; nor is it an argument for excluding perspectives solely because they offend prevailing moral codes – another form of censorship – or an insistence that everyone should fight every battle, since expecting constant engagement is itself a privilege. What strategic empathy demands is the harder, slower work of engagement without collapse; of engagement without turning every encounter into performance, and without retreating into the self-righteous safety of purity. Because Consensus Aesthetics falters when there is no consensus. Or rather, it collapses when consensus is treated as a precondition for discussion rather than as its desired outcome.16

In that sense, strategic empathy is not soft or conciliatory at all. It is rigorous, confrontational, and asks institutions and individuals to treat disagreement not as a failure but as evidence that something real is at stake. Today, the spectacle of rising reactionary and polemical discourses online, performed through the algorithmic theatres of YouTube channels and debate formats like Jubilee and endless culture-war panel shows that feed off outrage, are thriving because they acknowledge conflict in the most extractive way possible: stripped of context, turned into content, and sold back as entertainment.

Jerseys designed for Crit Club Düsseldorf at K21 on the question ‘What is more important: modern art or contemporary art?’ The design reflects the often‑unspoken competitive dynamics between institutions, highlighting how public communications rarely acknowledge one another’s existence – revealing another layer of Consensus Aesthetics in which institutions perform harmony while quietly competing for visibility and legitimacy. Courtesy of Cem A.

What art institutions could offer, if they dared, is the opposite: a slower, more deliberate arena where conflict is not exploited for clicks but worked through, however uneasily, in the service of something larger. Because no matter where you stand on the political spectrum, the art world functions as a bridge. It connects capital accumulation at its most rarefied to the public sphere at its most ordinary. Since the 2008 financial crisis, that bridge has grown increasingly unstable. On one side lies the art market, dominated by the interests of the ultra wealthy, who use art as asset, spectacle, or shield. On the other lies the promise of art as a public good, tasked with education, and accessibility. Institutions are tearing themselves apart in this tension, trying to serve two masters that are structurally opposed.

Perhaps there is no way to resolve that contradiction. The art world can pretend otherwise, but it cannot escape the reality that it operates in an age of extreme inequality. This is the deeper conflict Consensus Aesthetics seeks to avoid: not just disagreement inside the field, but the structural fact that art is suspended between capital and publics. Sooner or later, the institution has no choice but to reckon with this tension, however much it tries to smooth it away.

If there is a pragmatic way forward, it lies in cultivating forms of dialogue that neither deny conflict nor capitulate to it. Strategic empathy could be that mode: not reconciliation, not consensus in the old sense, but a framework where different sides can at least remain audible to each other. The art world’s risk aversion and claimed neutrality could, in fact, be recoded as an open forum capable of hosting disagreement and dissent, providing a structured space for public dialogue around contested issues. In this sense, the institution itself becomes less a shield against conflict than the host for it: the site where disagreement is staged, held, and – if we are lucky – transformed.

Jonas Staal, Nadja Argyropoulou, Basma al-Sharif

Shela Sheikh

Y7