- Mission Statement

4. Online/Offline Forms of Dissemination

Muhannad Hariri, Al Hassan Elwan, Günseli Yalcinkaya

Mission Statement 00: Why Now?

Below is a lightly edited transcript of the third session of Ibraaz Mission Gathering 00: Why Now? which took place on 21–22 February 2025.

Panellists: Jonas Staal, Nadja Argyropoulou, Basma al-Sharif

Moderator: Aya Mousawi

Respondents: Ashkan Sepahvand, Anjalika Sagar, Sam Samiee, Gaurav Sinha.

Aya Mousawi: For those of you who don’t know me, I’m Aya Mousawi. I’m a cultural producer, curator, and strategist. I’ve been working in the art world for over 15 years now, doing exhibitions and projects in different cities throughout the world, and I’ve often focused on looking at how we bring people together and how to bring communities together. What does community mean? How can we grow communities and audiences organically? That idea brings us to our panel today: who are our audiences, our users, our protagonists? How do we map out this ecosystem? How do we bring these people in? Who is the community? What is community for us and for this institution? As a note on the terminology: I think that the words ‘audience’, ‘user’, and ‘community’ are a little problematic, a little limiting. I know that we have a little beef with all of them. I don’t think we have enough time to unpack that, so I’m going to use the word ‘community’. I think at the root, the word embodies the thing that we’re trying to build, and I think we should be reclaiming it.

The way the session is going to run, I will continue speaking for a few more minutes, and then I’ll hand over to our amazing panel: Jonas Staal, Basma al-Sharif, and Nadja Argyropoulou – three extraordinary minds that I’ve had the pleasure of meeting only recently. Each will present their work and address some of these questions, and then we’ll open to the floor.

I wanted to share some thoughts about where my mind went when I thought about how to frame the session, about the idea and the importance of community, especially against the backdrop of the past year and a half. I actually thought about the moment that I first met the three of you just a few weeks ago, and it felt like a bit of a metaphor for a lot of the questions that we’re going to speak to. When I joined a call with all of them, within minutes, the conversation was about Palestine, and immediately that triggered a discussion around the genocide. Then with Nadja, we were doing the pleasantries of where we were working from, and she was in Athens, in her home, and turned her camera around and showed me her garden. In the centre of her garden was this big, beautiful olive tree, which naturally triggered a discussion about the tree, what it meant, and the projects about Palestine that she’d been working on.

In that moment, when we were still strangers and I had been pretty nervous to meet with you all, much like I still am right now, suddenly I felt really safe and at ease. I recognised that there’s an immediate human connection and allyship that is formed between strangers when you connect in solidarity. I think about that in relation to this idea of community and how we can feel safe with strangers. And I think in this past year and a half, I’ve actually felt safer with a lot of strangers that have been allies than I have with many friends and colleagues. I think about my personal community of friends and the demographics of people that I surround myself with, and it’s changed significantly. The very idea of what community is and how it serves us has entirely transformed. Where we seek out community is totally different within our personal lives, our professional structures, and obviously within the art world.

To bring it back to some of these initial questions. When Shumon [Basar] and Lina [Lazaar] first took me around this space maybe a month ago, I asked them immediately: ‘Who is this for? Who is your audience? Who do you imagine coming into this space?’ Shumon, almost instinctively, responded: ‘I imagine seeing a cross-section of the people at the protests in London’ – which is probably a very different answer to if I had asked five years ago.

As Tai [Shani] mentioned, I don’t think that we think of the protesters as the art world audience. There’s something really remarkable and really moving about the crowd at the protests and what they symbolise – a community that is global – and how solidarity transcends religion, culture, ethnicity, gender, nationality, age, wealth, and profession. The unifying common denominator really is solidarity, and I think that’s the central thread of who our audience is, who our community is, as I see it. And to put my formal and strategic hat on, I think we will do the more practical work of mapping out our target audiences and identifying groups of stakeholders and how we strategically target them.

But I don’t think that we can build a cultural institution today and look at who our audiences are in a traditional way, because I think the very idea of what community is has changed, and our need to congregate in these spaces has changed. Something Nadja said in reference to some of the projects that you’ve worked on about Palestine – and I hope you’ll speak to this today – is that people need these spaces to come together; that in hard times grief is unifying. I think about that in relation to this institution and how we think about who our audience is, now more than ever. I think we need to surround ourselves with our allies, our peers, our communities. How do we create a safe space for them? How can we invite them to become participants and not just observers? A question I think we’ve asked many times today.

To close on something that Jonas said, and again, something we’ve referenced: there has been a betrayal by the art world. In light of that, how can the public and the community really trust this space? I think those were some of the seeds of framing and thinking around this talk.

I’m going to hand over to Jonas Staal, a visual artist whose work deals with the relations between art, democracy, and propaganda. He’s the founder of an artistic and political organisation, New World Summit, which launched in 2012 and is ongoing.

Jonas Staal: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure to think together with all of you. Normally when institutions invite you to talk about institutions, I would advise ‘don’t go – it’s a terrible idea’. But in this case, it’s a different kind of gathering with a deeper common purpose and I’m very happy to be here.

We were asked to introduce ourselves. I’m an artist and a propaganda researcher, meaning I research the role of contemporary propaganda, with a focus on the role of propaganda in capitalist democracies and the role that art and culture play within it. This informs a key aspect of my practice that I describe as ‘organisational art’, which means thinking of artworks and creating artworks in the form of alternative institutional formations.

So, for example, the Propaganda School (2023–ongoing) is a school that researches different categories of contemporary propaganda through an ever-changing faculty. It’s an artwork in the form of a school, a particular type of school that, at present, doesn’t exist.

Jonas Staal, Propaganda School (2023–ongoing). This iteration took place at Propaganda Station (2023), PLATO Ostrava.

Another example of the artwork-as-organisation is the New World Summit (2012–ongoing): a series of artworks in the form of alternative, temporary parliaments made for and with stateless and blacklisted organisations – organisations at present prosecuted in the ongoing so-called War on Terror. It’s the artwork-as-parliament.

Jonas Staal, New World Summit (2012–ongoing), Sophiensaele/7th Berlin Biennial, 2012.

A third form of organisational art that I practise is titled Training for the Future (2019–ongoing), an artwork-as-training-camp. In this training camp we train in the use of different tools. Tools essential to organise protest choreography or transnational campaigning. Tools essential to reclaim the means of production to organise the future.

Jonas Staal, Training for the Future: We Demand a Million More Years (2019–ongoing). Training by Alternative Disability Quality Artists, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, 2022.

And the final example is the artwork-as-court, in this case the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021–ongoing) that I co-founded with lawyer, writer, academic, and activist Radha D’Souza, who you already heard earlier today and who will also be speaking tomorrow. The Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes organises public hearings to prosecute states and corporations for climate crimes not only of the past and the present, but also against the possibility of future life: crimes of the future.

Jonas Staal and Radha D’Souza, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021-ongoing). Installation view: Framer Framed, Amsterdam, 2021.

That is a very short overview of my organisational art practice. It’s an attempt to retool and repurpose what remains of public institutions to prefigure the kind of institutions that we desperately need. And when I say, ‘that we might need’, I relate that very directly to the needs of organisations that I’m an active member of, like Progressive International and the Kurdistan National Congress. For me, this retooling, this repurposing of the remnants of public infrastructure, is directly related to social movement and organising work. For me, there is no contradiction in engaging in cultural work and organising work simultaneously; for me, one creates the conditions for the other.

What’s important in these examples of organisational art projects I shared with you in relation to this idea of the ‘public’ or the ‘user’ or the ‘audience’ is, I would say, the ‘death’ of the audience. Instead, the audience is reconceived as trainee, or public jury, or constituent. They are part of an emerging collective, an emerging community: a people-in-the-making. They are my people and they are the people I am a small part of.

Also, these audiences – these publics, these constituents, these collectives, these people-in-the-making – are not present in my projects accidentally. When Radha D’Souza and I organise public hearings of the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes, we organise an organisational artwork, but we also organise a public: we decide beforehand who we want to be in there. Bourgeois art institutions produce bourgeois audiences. If we want to do it differently, we have to campaign as much for the existence of the public we want in the room as we do for the existence of the artwork. In our case, this public consists of communities that are directly tied to the witness testimonies and the struggles that are being brought into our courts, for example. We want progressive policymakers, activists, organisers, students from conflict studies, rogue academics that are abandoning these impossible institutions that we call universities. We decide beforehand who our public is. We have to compose a public as much as we compose an artwork.

In relation to our discussion today, I think who Ibraaz is for has already been identified in some ways: every worker that was fired for speaking out against the genocide – that would be a good start. I imagine Ibraaz as an institution built from the coalitions that are emerging in and around the Palestinian freedom movement, which is a broad, uniquely cross-class, and a potentially majoritarian coalition that moves across the fields of journalism, academic work, activist and organising work, cultural work, and that seems to find shared ground in a common project of collective self-determination, and the self-determination of Palestinian people is central in that.

This coalition confronts both the existing neoliberal warmongering forces in our society, as well as emerging neo-fascists, which have undermined our collective self-determination in a whole variety of ways when it comes to compromising our access to education; our access to cultural work and the means of production of cultural work; access to mobility; to housing; to health care; to social resources. Across this popular front that is emerging around the Palestinian freedom movement, there is a new constituency, a people-in-the-making: our people.

What does it mean to institute as part of and for this people-in-the-making is, from my perspective, the question that we’re faced with here. The display of culture is of course important because it’s about affirmation. But equally important is the propagation of this culture outside of the walls of these institutions to challenge and undermine – counter-propagate – the development of genocide as a new norm. The genocide in Palestine is also an ecocide. And the dangerous ‘overpopulation’ narrative the right is spinning around climate catastrophe, reveals the exterminative logic at its base: rather than changing systems, it wants to eliminate people. We are entering a world in which genocidalism replaces governance.

We have to propagate against those dominant narratives. But that also means to think of an institution as a toolbox. It means Ibraaz would need to be an institution that displays culture but also provides legal support; to be an institution that also supports cultural unionisation so that we have funds to boycott and to strike, to divest and sanction on our own collective terms rather than leaving each other to make fundamental ethical choices by ourselves. These past two years, years 75 and 76 of the genocide, too many of our comrades and colleagues were left alone, were left faced with geno-silence when their jobs were being taken, when their commissions were being taken, and we can’t let it happen: they take one of us, they must face all of us.

That also means we need an infrastructure that provides safety – material safety. It makes a difference when we know there is a fund that has our backs when needed. I would say these would be ways I would try to rethink an institution as part of these coalescing forces and peoples around our movement.

Aya Mousawi: Thank you, Jonas. I’m going to introduce Nadja, an amazing independent curator based in Athens, who has curated exhibitions with institutions and biennials throughout the world, with a focus on those in Europe. She has worked on projects about Palestine, which I’m sure she’ll speak to. She’s got fantastic grey hair, which I’m obviously a fan of. She’s very witty. In fact, I asked her to share some bullet points ahead of this session so that I felt a little bit more prepared, and what she essentially sent me was four very cryptic riddles and signed off the email with, and I quote: ‘I’m not sure they clarify things, but then clarity is overestimated.’ Upside-down laughing emoji. So, I’m going to hand over the floor to you to share with us some riddles.

Nadja Argyropoulou: Thank you. There’s been a form of ‘resisterhood’ that brought me here, starting from Myriam Ben Salah, my very good friend who introduced me to Lina [Lazaar] years ago, and also Stephanie [Bailey], who I met long ago in Greece, and then you Aya. I am happy to contribute to wherever this leads.

As to the clarity question from my earlier conversation with Aya: I totally agree with Francesca [Albanese] that we need the clarity of the moment, but I think we don’t need the kind of clarity that binds us to certainties and absolutes. What I prefer is a kind of non-clarity, or a form of precision that pushes over the edge of certainty and creates strings of thought that can ‘confound the wise’. I think of it as a form of resistance against the urge to be right, to be wise, to be ‘institutional’, and it includes us as we are posing these questions. Questions that need to be repeated, re-posed again and again and from every possible angle.

I guess the way I see the question of the institution – and its ‘audiences, users, and protagonists’, as per our panel’s title – is more from the point of view of a curator’s work, which, to my understanding is always para-institutional. Good curators are para-instituting all the time because they are (un)mediating and acting and questioning not as an exercise in style and ambivalence, but in order to free things, to make them possible through odd mixtures of solidarities and antagonisms, uncommoning and disidentifications, also assembling and disassociation.

To do that, you really have to work around, against, through, and para every kind of reality, which means next to and beyond things. And I’m always hoping that big institutions, including in academia, can see something in that uncertain movement. Yet I have mostly experienced the opposite and this is why I became an independent curator.

Now that I hear it out loud, even this sounds a bit like a joke: ‘an independent curator’. How independent can one be in the art field? Beyond navigating the common financial hardships and precarity of this independence, one is faced with several kinds of complex challenges even when one works with the structural container instead of for it. Still, we have to work against dominant narratives, in the gaps and cracks left by them.

So I am here today, as you are, trying to practise-in-gathering a form of radical questioning, a jam session, beyond institutional critique clichés, vis-à-vis the birth of a new institution, Ibraaz, under the strain of specific sociocultural, economic, and geopolitical crises. I’m reminded of this lovely phrase from Jack Halberstam’s preface to Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s The Undercommons (2013): ‘you are always already in the thing that you call for and that calls you’.1 So we are here and we are in. As I was trying to figure this out from the point of view of participants and participation, access, cultural consumerism, the non-accidental coming together that Jonas just talked about, I resorted once again to the old Benjaminian montage trick: ‘I needn’t say anything. Merely show.’2 By sharing images and stories from my practice with you, maybe things will come forward through the eyes of your presence. And maybe they can be useful in the context of this panel.

I realise I have selected several images of clotheslines that document presences, actions of community-making – wild gatherings outside urban contexts and inside the art-life confluence. Clotheslines instead of or along with artworks. What if clotheslines entered our art books and exhibition catalogues? How would they destabilise their function and energise their audiences?

Then there are images of very dense church mosaics that serve as visualisations of assembling and communing, where not even one thing can be removed without everything collapsing. And this is very much how I understand differentiation without separation when I consider the various bodies in action where art is involved.

I was also talking to Aya about this idea of ‘the rub’. The rub is how poets like Moten and Andreas Embiricos have chosen to talk about how things are affective and affected – how they are rubbing together, and how they rub off onto one another in the haptic way that exists independently of our bringing them together. The rub is maybe a better way inside how we assemble, and how our ‘audiences’, communities, or alliances are co-realised and metamorphosed.

I guess I am struggling with the fact that language is a prison in the separation it produces, and we have to create an outside from within this very enclosure and its normative function and then also question the consolidation of this ‘outside’. So why, for example, not invent new words to talk about audiences – why say audiences? Why say networks? I have grown to hate the word network because of the way neoliberal discourse has been abusing it. Even if you are networking the network, which is good in the sense of evading the network, still you are in the network because you are in the language of the network. How about ‘webbing’ instead of ‘networking’? It’s something that a spider does.

And why not ‘make audiences’ by shocking all involved agents – artists, viewers, various publics – out of their language of perception and into the slang of unrecognition and unfamiliarity.

In the images projected now you can see the set-up of the exhibition ‘Hell as Pavilion’ I curated at the Palais de Tokyo in 2013 at the height of the global economic crisis when Greece was becoming part of the disaster porn. The exhibition was titled after, on the one hand Jean-Luc Godard’s odd cut of the word ‘Hellas’ (‘HELL AS’) in Film Socialisme (2010) and, on the other, after the modernist display device of a ‘pavilion’.

The exhibition was awkwardly dense, with no appropriate distance between the works – a kind of disrespectful assembly, or a pavilion in ruins that in its entirety (works on display and events) spelled out a crucial question: Hell is how we come together but also how we do not come together; but who is this we? And how is it represented? Posing this question from a country, Greece, that has always been in crisis and has always been in debt, and has long been formed by the foreign gaze, the exhibition made its visitors partners in estrangement – a feeling that Greeks were sharing while being considered toxic monsters, narcissistic insurgents who put EU structures at risk of contamination. Feelings also shared by all those who are being guilt-tripped by capitalist thanatocracy.

Visitors were moved out of an elaborately prepared and presented political ‘context’ and carried, through the unpredictability, the absurdity even, of its display and works into the ambivalence, the lack, the missing beat at the heart of that disorienting historical moment. ‘Hell as Pavilion’ was about the cost of escaping the proper and the proposed in life and politics. The exhibition in its entirety talked the talk and walked the walk.

So in the same spirit of para-instituting, I propose to drive a stake into the heart of the undead elements that precondition the existence of an institution, into the heart of the beasts that are enslaving us when instituting happens; to end the kind of zombification that we see everywhere in existing institutional settings; to not go very gentle into a long night of considering community-making; instead of an endless workshop – a cautionary tale that often hides aloofness – to risk taking to the streets, to the neighbourhood, to the near and the far, out, into; to make it personal as much as it is political. I think that scale-shifting – the tension between minor and major – is important to the growth of a new cultural ecosystem.

Family Business, Palais de Tokyo, 2014. Courtesy of Nadja Argyropoulou.

Family Business was a really small space, a micro-institution, founded in New York in 2012 by Massimiliano Gioni and Maurizio Cattelan, which I joined as a guest curator later. It was eventually moved to Paris and reimagined for a few months as a tiny, roaming portal, out of place but within the grand spaces of the Palais de Tokyo.

As you can see in the projected images, it was positioned at the entrance – on the brink of the institution one could say – and could actually be visited without a museum ticket. It hosted weird events and forms of resistance: a 21st-century salon des refusés. It evaded various directives – like timely programming, clear press info, etc. – to the dismay of the institution.

I am thinking of curiosity that is care, concern, commitment. I worked on the photographic research project Wor(th)ship, by Tassos Vrettos, that visited, for the first time, makeshift places of worship of refugees and immigrants in Athens (2010–15). Marginalised communities shared their secular lives, their faith rituals, and stories of joyful ingenuity with Tassos and others through the research and exhibition. They eventually gathered at the Benaki Museum during the presentation of the project in a demonstration of trust and friendship that abolished the hierarchies of creating and exhibiting. A complex body was revealed in the undercommons of a city largely lost amid real-estate growth and overtourism. Long-term ties were made. The Benaki Museum continued to talk with those communities after the end of the show. To build and sustain trust is to relinquish power, authority, and control, and this is a highly political choice for every institution. ‘Safe spaces’ are a highly popular claim in institutional lingo but are still far from being a reality actively pursued and an equality carefully sustained.

Even though multicultural Athens is a relatively safe space for voicing support for the marginalised compared to many other cities abroad, things are far from ideal. There is a surviving libertarian spirit of defiance in Greece’s urban settings and there has been a philo-Arabic political past in the country. Civil society platforms and working class coalitions are mostly active and disruptive. But conservatism and ignorance are also present – as we know from the growing presence of far-right parties. And people from marginalised backgrounds or those without citizenship are ever easier targets of bigotry.

In the case of the Palestinian genocide, Greek public and private institutions have been deafeningly silent. The current right-wing government has been forging stronger ties with the Israeli government under the pretext of a need for strategic geopolitical alliances vis-à-vis the ‘Turkish threat’. Pro-Palestine protests may not be interrupted with the kind of police violence that we witness elsewhere, but brutality still lurks for the more vulnerable and has been taking many faces. People are being singled out for not complying with the dominant narrative on this issue, many are deprived of sponsoring in the cultural sectors and are vilified through media or slyly excommunicated from institutional environments. Small-scale assemblies and bottom-up alliances are demonstrating strength and resilience, but this is a constant struggle that demands a lot of energy and courage. These are our communities and part of the kind of instituting we should seek.

Even though we are approaching the question of audiences and community-making from London, the base of Ibraaz, it is maybe useful to consider the lessons learned in peripheries. I am thinking of the small islands dispersed in the Aegean Sea – this minor archipelago. My experience of artmaking and sharing in this context was one that replaces long ‘relational’ processes and patronising approaches with more instinctual choices.

Nisyros, Tilos, and Ios are small islands, which are part of the Dodecanese, that suffer from environmental crisis, overtourism, neglect, and erratic state policies. While we were there for art projects, we opted for the kind of tactics employed by the Greek Bouloukia, the amateur theatre groups that once roamed the Greek countryside, presenting their plays, mingling with locals, and meddling with their affairs in the most natural and undesigned ways; they changed each place as they were changed by it. We learned that over-planning does not work in certain circumstances. Be adaptive, do as the locals do. Maximum effort in minimum time just for fun and not for big press visibility is the kind of expense that disarms people and builds ties in micro-environments where unpredictability rules and life is idiorrhythmic. Think alternative and alternating tactics instead of immovable strategies.

I am thinking of the lesson learned in the municipal context of Chalandri, the old Athenian suburb where I have been working for the past three years. With a mixed population, this is not the hyped city centre where progressive art events root and thrive. And yet, the rather big and multilayered exhibitions and public programmes organised in an abandoned public building with the participation of various local agents – The Forest’s Riddle (2022), Outraged by Pleasure (2023), The Collective Purr (2024) – gathered very different people of every age, background, class, and outlook, and actively cancelled the endogamy that often characterises the art world. The ongoing Palestinian struggle for self-determination was celebrated there, as were matters of social and environmental justice, queer arts, a DIY ethos, technology, and degrowth.

I am thinking of online audiences that should also be nurtured. Not through audience-building marketing gimmicks but via meaningful content that multiplies connections and reinforces storytelling. And it matters what stories are told. Trypa: Stories of love, anarchy, care and disruption as are told with Teos Romvos and Chara Pelekanou (2020-21) was an exhibition about the lives and works of two very important eco-anarchists, co-curated with Linda and Daniela Dostálková for Plato in Ostrava, Czech Republic. The exhibition shape-shifted, through the pandemic and via the input of curator Edith Jeřábková, into the ongoing, online, publishing platform Octopus Press, named after the legendary anarchist bookshop in Exarcheia, Athens. The original exhibition was swept far away into uncharted territories and other dimensions via the generosity and solidarity of a special kind of instituting.

Aya Mousawi: Thank you, Nadja. I’m going to hand over to Basma al-Sharif, an extraordinary Palestinian filmmaker, artist, and thinker, who has been working nomadically across the Middle East and Europe, and is now based in Berlin.

Basma al-Sharif: Thank you. I actually forgot for a moment that I needed to present! I was where you were, listening carefully. It’s really nice to be here. Everything that I wanted to say, I’ve just been reshuffling or revising in my head because it’s a huge relief. It’s such a great comfort to hear the things that you are afraid you won’t hear immediately being said and being questioned, and with kindness and with generosity. I was very nervous – I’m still nervous – but somewhere, I’m very relaxed.

I’m Palestinian, I’m born in the diaspora, but I grew up going to Gaza every year of my life, my family is Gazan, not refugees in Gaza. One of the things that was very difficult after the genocide began was these invitations to come and speak about my work were often spiked as soon as Palestinians are being killed. That has happened since I started making work. I graduated in 2007, the first Gaza War happened in 2008–09, and I would see these upticks of interest in my work, very similar to what you were saying: ‘Oh, there’s a conflict and we’re interested in it.’ So there’s this feeling of exploitation and wanting to keep your integrity, and not wanting what you make and show to be at the service of an institution’s sudden whims.

With Palestine, that’s been incredibly devastating. That there’s a very clear connection that the more we die, the more the art world is interested in us. As soon as there’s a ceasefire it plummets back down to like: ‘Okay, what’s the next thing?’ Gazans are left to rebuild and to deal with the much more difficult – I mean, I’ve survived one of Israel’s wars, but I feel the moment when the spotlight is off is the most devastating moment. It reminded me that I was accepting these invitations and becoming robotic and empty, and talking about my past and soapboxing, and cursing the art world and all the betrayals that have happened.

Then I was invited to a festival in Tunis, coincidentally, and I was starting to do the same thing. I was collecting my thoughts and speaking about a work that I made, and I looked up at the entire audience – which is somehow happening again, maybe gladly so – and I realised that I’m speaking to my peers. They’re not necessarily Palestinians, but everyone is feeling what I feel. What’s happening in Palestine is a repercussion that is happening to all of us in that audience, and it was incredibly powerful, and it made me think about the reason I had started making work, and how I started making work nomadically. I say nomadically, even though that comes with immense privilege and is also just a consequence of being in the diaspora and not having a country. Always being a guest in a country is a very particular experience because you know that at any moment everyone can turn on you and decide you’re no longer welcome for whatever reason. When you’re born into that, which all of the diaspora feels, passports or not, it’s a very precarious way of existing. It’s always knowing that you have to be on your feet and ready to bolt, basically, and it’s how I developed my practice.

I mostly grew up in the States. We were in France and then we were deported from France and went to the United States and when I started making work, I left the US. I started my first year of university the week of 11 September, and then it was the Iraq War. The first war in Gaza happened shortly after I left, but I decided that I needed to understand from which perspective am I speaking? Who am I as a Palestinian in the place that I am? And not to do this thing of, like, ‘based in Paris and Ramallah’ or ‘Berlin and South Africa’ or whatever, just not to be two cities, but to be a person in a place with multiple perspectives. That sort of caused me to start moving every few years – unintentionally – between Europe, the US, and the Middle East, to try and understand what that meant and how it shifted from place to place; and to understand how different people related to Palestine and how we were either lauded or vilified but never neutral. This was a very particular thing I was trying to work into my work – to not make it something that explained our struggle, but to force people to reconcile it for themselves through the work.

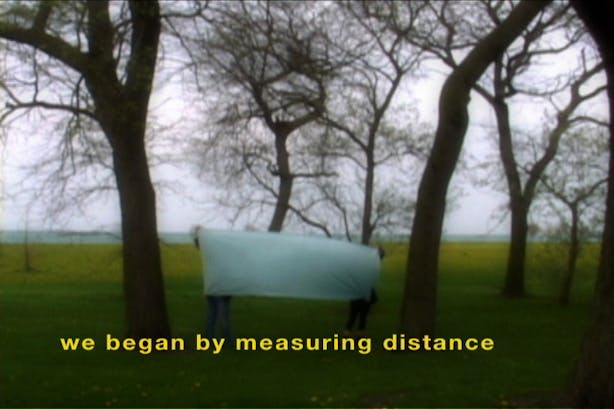

The thing that is playing on screen is a film called Ouroboros, which premiered in 2017, but I started working on after the 2014 war in Gaza, which was the third large-scale military attack on the Gaza strip. It was also the year that the majority of my immediate family left Gaza, and it came after several years of making work and moving around. I thought as a Palestinian but was educated in the West, and I realised that what I could do, what my power and my privilege could afford, was to infiltrate spaces with our narrative. To use the language of the West, but then to enter Palestine into these niche experimental film and visual arts worlds, but to have it coded in the West’s language. I thought that this would be my special power or my special privilege.

By the third war, I’m sort of experiencing again what I experienced then, which was a realisation that, actually, these platforms that are supposedly being made for us are false. They’re not real. They’re there for them. They’re not for us. Because if they were, then something would stop – then it wouldn’t be progressively getting worse every year. This was the thing that started to become very clear to me. Every year, the situation got worse, even though people knew more and more about the occupation, or understood it, or were even in solidarity with us. So, I made this film, which is a feature-length film. I work between cinema and installation and hadn’t really set out to make a feature-length narrative film, but I wanted to make a film that paid homage to Gaza, that resisted describing our struggle, and that really forced us to think about the future. If this is happening in Palestine, what does that mean for the world?

This was in 2014, not today, but just to say that civilisation has failed us, and not ‘us’ as Palestinians, but us as human beings: what does that say? For me, it says we need to take Gaza out of its isolation and to put it in dialogue with other cities, other histories, other potential futures, and to really refuse the idea that the solution to the problem is more information. Because it’s not for lack of information that our situation persists. There’s a wilful refusal to see what is happening in Palestine as reflecting on you, on your privileges, on your security, or on the erasure of certain things where you live. A refusal to connect it to gentrification. A refusal to connect it to police brutality. A refusal to see it as essentially a colonial racist issue. I mean, I was shocked when people started calling Israel a settler-colonial country. I mean, this was not happening in the mainstream for years. And actually, it’s been incredibly lonely, I think, as Palestinians, to feel like these things happen and we’re just dealing with it alone, and it’s very clear to us that it’s affecting everybody. But for some reason, it has just been our issue, and this is one thing that we’ve been liberated from, I think, since October: the belief that there is anything acceptable or viable about the state of Israel.

I decided to explain this film, and how I developed my practice in thinking about audiences, because it’s something that I’ve been trying to figure out with other people in Berlin. When working in enemy territory, what do we do? The institutions have clearly failed us. There’s nothing that we can do to change them, so how do we move forward? Because we’re not going to stop making work. Myself and so many others don’t feel that our work is the thing that will change the political situation, but if we didn’t make this work, imagine where we would be. It’s not activism and it’s not on the ground resistance or change, but institutions and artists have the potential to bear witness to the present, to provide us with an alternate way of seeing things, to step aside from the immediate and allow us room to imagine and to fantasise about the future.

Thinking about audiences is the way to decide how a space is made: the space is the audience, actually, in the same way that I was thinking about my work. Yes, I could have made a film that answers the questions I know people have – questions that have already been answered – or I could decide I’m going to write it in a completely different way, and then the audience will form around that work. That is to say: forming the audience that you want, pushing them to deal with questions like: ‘Okay, why is she not revealing the information or why is she not spelling out the history of the struggle in her work?’ Or: ‘Why are things not factual, or linear, or narrative? Why are different languages being spoken?’ This kind of thing.

To think of spaces as they are for us, or made and shaped by us, this is how we have to start to think now because we can’t rely on the institutions and the mainstream world that have said over and over: ‘We are not defending you, we are not standing by you.’ I don’t want to say wasted effort, because of course one has to resist, and one has to try, but I think a year-and-a-half on, we can take the hint and not respond but start to create what we want to make. I very much appreciated so many of the comments that were made; it’s not a coincidence that we’re here and we’re not guests here. We are the thing that is shaping the cultural sector. They can’t get rid of us. There are too many of us. They’re not making it viable for us to go back home, so we shouldn’t think of ourselves, and what we do here, as guests in someone else’s territory.

We have created the fabric of these cultures, no matter how much they resist or try to make it seem marginal, and that’s what this space, I think, has the potential to do. This is a London base responding to the audience, not as a foreign entity, not as an alternative space. This can be a mainstream space – in the positive sense of being one that defines its audience through what it wants to do.

Aya Mousawi: Thank you. I have a question and it’s addressed to Basma but it’s obviously open to everyone. It’s something that Adam [Broomberg] touched on, regarding this idea of the diaspora and our global networks and how we kind of plug in. You’re based in the diaspora; you’re making work that is rooted in Palestine and Gaza; the Ibraaz tagline is ‘networked to a world of worlds’ – maybe we should change that word. This idea of this institution being rooted in content, in artists and creatives and voices that are from the Global South, how do we tap into audiences and communities on the ground there?

This is a question for all of us: how can we bring in those communities that do not have the privilege of being physically in London? I know we’ll have a website, and we’ll have online content, but how do we really affect the communities? Is it through funds? What is it that we can do to really tap into and make them feel that this is a safe space also for them? I really want to practically know how we can do that.

Basma al-Sharif: I have a very brief answer for this. I mentioned that I really didn’t want to be an artist based in two cities, because that seemed to be the cringiest or privileged-laden position, even if that’s actually what I was doing. I really wanted to think about what resources I had available to me when I was based in Beirut or Cairo, and only working with those resources to define what the work was – but then, understanding that if I showed that work in London or Paris, why divorce these two things from each other? How do we make this connection – if you’re a Tunisian artist or a Palestinian artist or a Libyan artist, but you’re based in London – how do we bridge this gap so that these massive and terrible discrepancies between being outside and inside are more sutured so that audiences are not like: ‘What you’re doing makes no sense, but what he’s doing is also not your experience – you don’t fight with the same risks.’

How do you extend what you have here into their space? And how do you consider what that space gives you where you are? I don’t actually have an answer, but to think about how to bring the other site into a western or northern space is a really important thing. Sometimes I think it’s even just a matter of language. I mean, one thing we’re talking about in Berlin is like, why don’t we just do things in Arabic? Like, fuck it. The people who don’t speak Arabic won’t understand it, but then next week it could be something in Spanish, or it could be something in Turkish or Farsi, and people could still come, and okay not always understand. But isn’t that better than everybody doing it halfway in an English that’s broken, as a way of not modifying yourself once you’re outside of the place that you’re connected to?

Ashkan Sepahvand: Thank you Basma, I was thinking about this anecdote during your presentation. It departs from a statement Terre Thaemlitz, aka DJ Sprinkles, made in an essay about ‘queer sound’, that it’s a secret ‘for those “in the know”’.3 I remember going to hear DJ Sprinkles play in Berlin some years ago. She came in 12 hours into the party and started playing their set – low-BPM house tracks with lots of archival samples of interviews from the AIDS crisis. It was moody, dreamy, confusing, and not necessarily danceable, but it sounded very interesting. I remember how the dance floor just cleared. Or at least, all the ‘basic’ party people just left. That’s when I understood how queer sound works, its intended effect. If you know, you know. It’s an approach that communicates ‘something for someone’, rather than ‘everything for everyone’. I wanted to share this because I think it’s a useful approach for tackling the problem of ‘audience’.

In my short experience of the UK, I feel like institutions insist on this ‘everything for everyone’ delusion, which for me has always felt that they view the public as unable to think for themselves – in short, as stupid. And so, programming aims to stupefy the public. Everything has to be accessible and simplified, ‘everyone is welcome’. I’m more interested in a kind of anarchistic approach that recognises the complexity of intimacies, how they do or do not intersect and interact. Circles of intimacies, you know, friends of friends, friends of friends of friends; and to be sure, not everyone is friends. In between, something is lost or slips away. There’s the power of the secret and of concealment: what stays between one circle and doesn’t necessarily trickle down to another circle. How can this be a way to think about multiplicities or simultaneities of access and exposure, of incongruent audiences?

Anjalika Sagar: Thanks, Ashkan. I’m thinking about when Gayatri Spivak critiqued the jubilant cry of the World Social Forum’s mantra, ‘Another world is possible’, and its western formation and failure to address the complexities of global inequality and the worlds of the subaltern. In the wake of neoliberal confusion, Spivak’s critique is fundamental to remember, and this may seem tangential for a transnational, itinerant nomad and a wanderer.

It doesn’t need reminding that the white supremacist corporate agenda, the Hadean financialised unfurling that seeks to set people against their own best interests let alone each other, has brutality at its core. The techno feudal enclosures and their boring dead-world-making agendas, built on corporate sociality, is now based on the total erasure of a public. What is a public without public education, without diverse public media, without protest, without public communication channels. The aspiration towards wealth, towards business within a form of educational imperialism is where we are at.

As for how art has fared, remember the laughable language of the naive vision of the neoliberal biennial circuit, which would call its landing strip – even a city like London – local, when in fact, this place has been generating a multi-ethnic diasporic matrix of anti-colonial movements in so many ways for generations, and has also been operating despite institutional arrogance. Things are happening, gestating. There is a pulse of resistance – in clubs, in festivals, in community centres, in schools, around Black kitchen tables, in Black libraries – and they’re happening in resistance to the fact that the education system in this country is a financialised one. Therefore, the majority of those who receive an education are the rich kids who get to go to university, and the neoliberal art world privileges those people who have access to that. I call it Smart Art – they want illustration.

Finally, one cannot avoid class if you’re going to think about politics at all in a city like London. You have to confront the desperate poverty, the migrants disappeared into the camps, and at least try and protect the lived aesthetics of sociality that Ashkan was talking about. There’s so much going on all the time, and has been for a long time, under the radar. All kinds of movements, groups, and meetings, where people are doing a multiplicity of different things. The May Day Rooms is a useful organisation here, where they’ve been collecting and looking at archives of the left in this city and beyond for a long time. June Givanni and the Pan-African Cinema Archive, for example, have been given space and real support.

Cultural elites want everything seen and exposed, as they are safer than most and veiled. In a city like London, I think we have to learn from movements. I grew up in salons, homes for symposia, ours was one as well. We lived in a beautiful old council flat opposite Primrose Hill, and one of the former directors of the Whitechapel Gallery in the 1970s lived in a big house next door. She walked around Primrose Hill with big amber necklaces. And in that house, Stokely Carmichael, Sarah Vaughan, Ruth First, James Baldwin – all these great figures – would meet to discuss apartheid, poetry, literature and politics. London is full of these anti-colonial histories and so is the rest of the country. There are many people who’ve been doing a lot of work for a long time within the privacy of their homes, because the public sphere has always been classist, racist; it has always been a struggle in their Majesty’s Kingdom.

The Saatchis and the reality TV giant Endemol, started it a while ago, this shift from the critical and experimental towards art as entertainment. I blame them, in their reduction of the public to a mute audience, an advertising space. Art advertising sociality misses the point.

In the protests, you see many people, I would argue that you also see the presence of people who haven’t had the privilege of being able to pay £10,000 a year for an education. You have people organising in many ways. But how to protect our movements? How do we organise and think together without putting our necks on the block?

Nadja Argyropoulou: I would like to address a couple of things, after hearing Basma talk about the sense of alienation we experience in art spaces and how institutional structures fail us when they avoid addressing life’s urgencies – and the bitterness that we feel when tragedies are hyped into the spotlight as ‘cases’ for political artmaking.

Allow me to share a story that reflects institutional failure in my home country. When the genocide of Palestinian people started unfolding, the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens – a museum that has recently been trying to up the ante in the country’s cultural sector – was hosting an elaborate exhibition titled What if Women Ruled the World? The press release for this big institutional show stated that the questions summarised in the title ‘are posed not because we argue in favour of the establishment of a matriarchy, but because the programme aims to invite reflection on whether there is an alternative to the dominant patriarchal paradigm that is seemingly leading the world to climate meltdown, environmental degradation, and war-induced destruction’.4 Yet the state-funded museum remained silent, either through the show or via related events, on the atrocities of the unfolding genocide-ecocide that mostly harmed women and children. It failed to address in any critical way the heated debates shared by cultural workers, artists, and the wider public.

A group of us felt that we had to voice our disagreement and organised a peaceful protest on 17 May 2024, on the museum’s grounds and during the opening of the exhibition For Dear Life, a retrospective of the anti-apartheid work of South Africa-based artist Penny Siopis. We did not aim to disrespect the artist, but we thought that this moment could extend and ground the apartheid question in a present history that was in the making. Reading out loud the names of artists killed in Palestine and of the museums destroyed under the Israeli bombardments, we unfolded our banners and chanted in unison, ‘for dear life, free Palestine’. The chant transformed Siopsis’s plea-title. A ‘public’, a community, was summoned by the chant, created on the spot, and claimed the empty space left by the institutional ‘absence’. The abstraction of Palestine took on a voice and circumstance humbled the theory often hurled around by art professionals. I think what I want to say by recounting this story is that antagonisms and their discomfort must be tended to and cared for by institutions. They are as vital as the commonings and affirmations that are usually endorsed and advertised. It seems that Ibraaz already knows that.

Aya Mousawi: I’d like to ask Jonas. If we’re thinking about the cross-section of the protesters, they aren’t your usual art world crowd. There is an art bloc and I’m part of the WhatsApp group, and that’s fantastic, but of the 300,000 people that show up on the streets, they’re not part of the conventional or traditional art world. Listed on your slide were progressive students, community organisers, activists, critical journalists, academics, medical professionals, cultural workers, and countless other constituents. In really practical terms, how can we bring non-art world audiences, that are doing a lot of the work of organising, into this space? And how can they trust this space, how can they become active participants and not just observers of an exhibition? I’ve addressed it to you, but maybe other people here might also want to respond.

Jonas Staal: For me, the first thing that’s important is not to assume anything. Often in discussions within art institutions, somehow people are spoken about as if they are outside of the room, even though they’re often in the room. In this room, I already know several people who are active organisers, activists, members of political parties, or unions, and do the work that they need to do. So many of the people we are talking about ‘bringing in’ are often already right here. Otherwise, we would probably not be able to have this conversation in the first place.

But if we speak about it practically, step one, I would say, is always hire a campaign manager. Communication is not advertisement. What we tend to call communication is often not communication. Communication is community work. It is building the trust of representatives of communities, of identifying community leaders – because the idea of the public as something that you can somehow address as a whole doesn’t exist. You address key people within an organisation or within a particular community. You build trustful relationships with them in order for information to spread to the people that you want to address, for which you also want to operate as a tool, as a space of affirmation.

This perspective of the political campaign is generally very helpful when it comes to deconstructing the mythology around a public. I don’t know how many times I’ve been in spaces and it’s like: why is it only us here? Who are we missing? Well, reorganise your communication department. Why are they only doing paid corporate social media campaigns? That’s not communication. So that’s the first step: to be extremely material and concrete about access. Not just in terms of what should be standard practice, like sign language or having organisers from the disability community as part of your communication and mobilisation team, but to ask the subsequent question, who do we want to have here? Not just any public, but our public – our people who need support and sustenance. This is not just a communication question; it’s a political question.

And I think that was very beautiful, Basma, when you said the space is the audience for your own work, and when you spoke the first sentence, ‘I was so happy to hear the things I was afraid not to hear’, because if we’re talking about spaces of trust and resonance and affirmation, that’s the first thing. That someone spoke for you, with you. You could trust that the words were carried by those other than yourself. That’s maybe the first step in so that we’re not isolated as hyper-vulnerable individuals that can just be taken out one by one by our enemies.

Sam Samiee: Thank you all. Multiple things that all of you said made me want to mention this, and it’s a bit messy, so forgive me for that. It’s not very formulated, but this comes from a place of experience. Jonas mentioned institutions and the toolbox that they can afford us. But this provoked me to mention that there are various institutional hurdles that we all have to jump over to get into institutions, to become an art expert or art mediator or an artist. That you should know certain things about Greek history, Roman history, European history, institutional ways of doing things, and how to write a press release, etc.

With the images that Nadja showed, which Basma showed, and with all of you and every other panel that will come – and thinking about everything that I think Ibraaz stands for – one way or another we have a certain relationship to Islam, like it or not. I say this as someone who is not practising, who is not a believer, who’s not defining his identity necessarily by his belief. I became Muslim when I moved to Europe. Before that, while I was living in Iran, I was not Muslim. I was who I was, but I came to Europe and thanks to European xenophobia and bigotry, I realised I actually had become ‘a Muslim’. And this is maybe a question regarding London being a place with a certain expertise, and with individuals that have intimacy with and historical understandings of Islam, or Islams. Because we were just mentioning this with Mona [Chalabi], that within Islam, there are other certain repressed Islams. Then you have all these tendencies, like ‘Lebanese are not Muslim, they’re Phoenician’; ‘Iranians are not Muslim, they’re Achaemenid’. Everybody goes to some ancient ‘ism’ that is repulsive at times. And from the experience of living in the Netherlands, I remember art schools, anarchist spaces, and the W139 artist-run space, where I began to address this issue and began thinking about it institutionally. Whenever the word Islam comes up, we choke on it. It’s just too big. We cannot digest it.

What would the future of Ibraaz be – according to you or anyone else in this room – if an intimate expertise, readership, or contact with Islam, is channelled without glorification, putting down, overcoming, forcing people to secularise, or excluding secular people, because they are not Muslims? That’s why I say it’s very messy. I can go on with many examples of how messy it gets the moment you mention this. You all have heard of the superiority of Europeans, because Judeo-Christian culture was digested so much that the secular European is perceived to do ‘clean’ institutional work.

But what about the audience that Nadja shows in the refugee camps that are raising Shia flags, which many Muslims repress as well? They say: ‘But those people never go to art institutes. Art institutes are not made for them. They want a place of worship.’ I’m not talking about opening the Tate Modern to hold Ramadan ceremonies. I’m not against that; I find that very fascinating. But what is the other way? SOAS and others are doing very close, intimate work on understanding the particularities of the history of Islam, in relation to Palestine, Iran, Afghanistan, etc., which can also crack open a place for people who traditionally do not find us to be their – to be our – constituents.

Gaurav Sinha: As a storyteller, what can Ibraaz learn from your experience, Basma, when it comes to format? If you think of content as a currency, which is about utility, benefit, and convertibility, how can we create content which can be exported and has the level of stickiness that will allow us to bridge the gap? What have you learned through your experience? I would love to hear more about that.

Basma al-Sharif: That’s a big question. I think it’s something we can learn from many different artists, but maybe to give a very brief answer that connects the two questions. Why is Palestine so uncomfortable for so many people? I think the resistance is really uncomfortable for a lot of people because if you say, ‘actually I don’t mind, I’m a Muslim by birth, non-practising’, that’s one thing. But if I say, ‘actually, I don’t mind if Hamas take over all of Palestine – I’m not as afraid of a woman who is a niqabi as I am of Israel,’ that terrifies them. Because it’s saying: I don’t accept the West. I don’t see the West as the ultimate horizon of values. We don’t believe in your democratic values. We don’t believe in your humanity.

This is the thing that’s at stake right now in Europe: humanity. I look to other Palestinians but also artists all over the world who don’t concede and don’t pander and don’t try to create safe spaces, as you were saying, where everything is resolved and we’re all on the same page and nobody’s triggered. I think if Ibraaz does that by looking at how other artists have done that, we are already moving forward.

Muhannad Hariri, Al Hassan Elwan, Günseli Yalcinkaya

Basma al-Sharif, Sophia Al Maria, Lawrence Lek

Kamel Lazaar