- Special Project

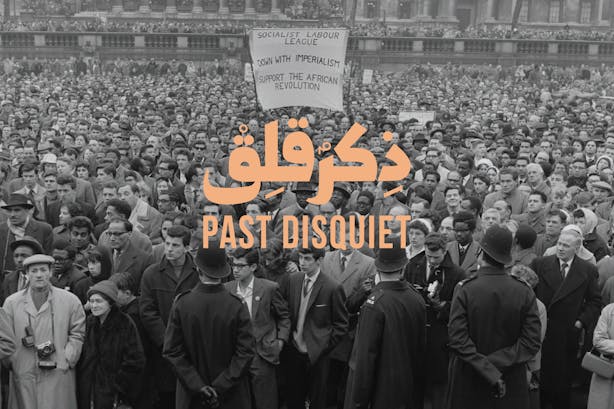

Past Disquiet: Excavating Solidarity in the Arts

A discursive programme by Kristine Khouri and Rasha Salti

The first in a three-part visual essay by Rasha Salti and Khristine Khouri reflecting on different aspects of their long-term research project Past Disquiet.

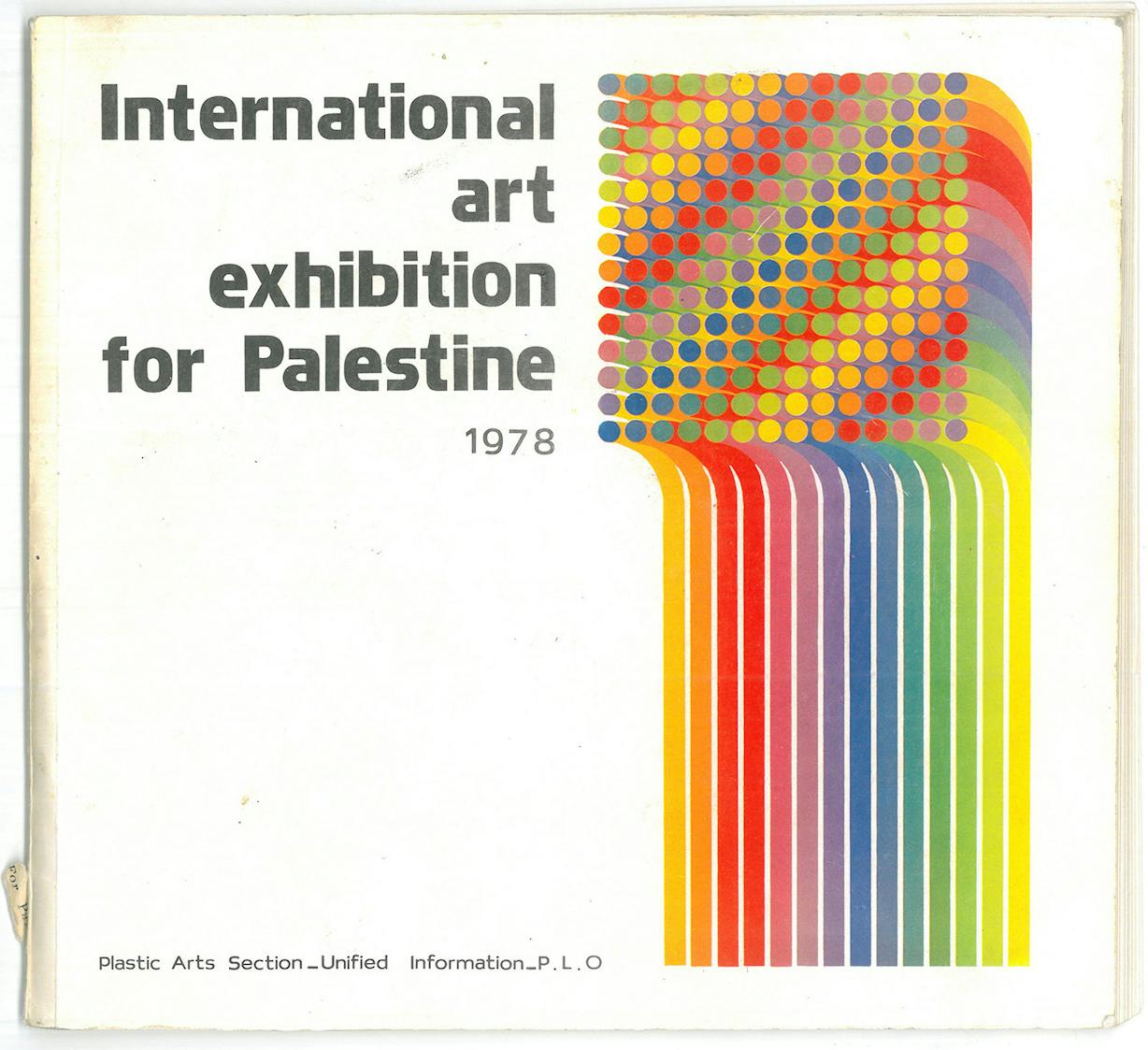

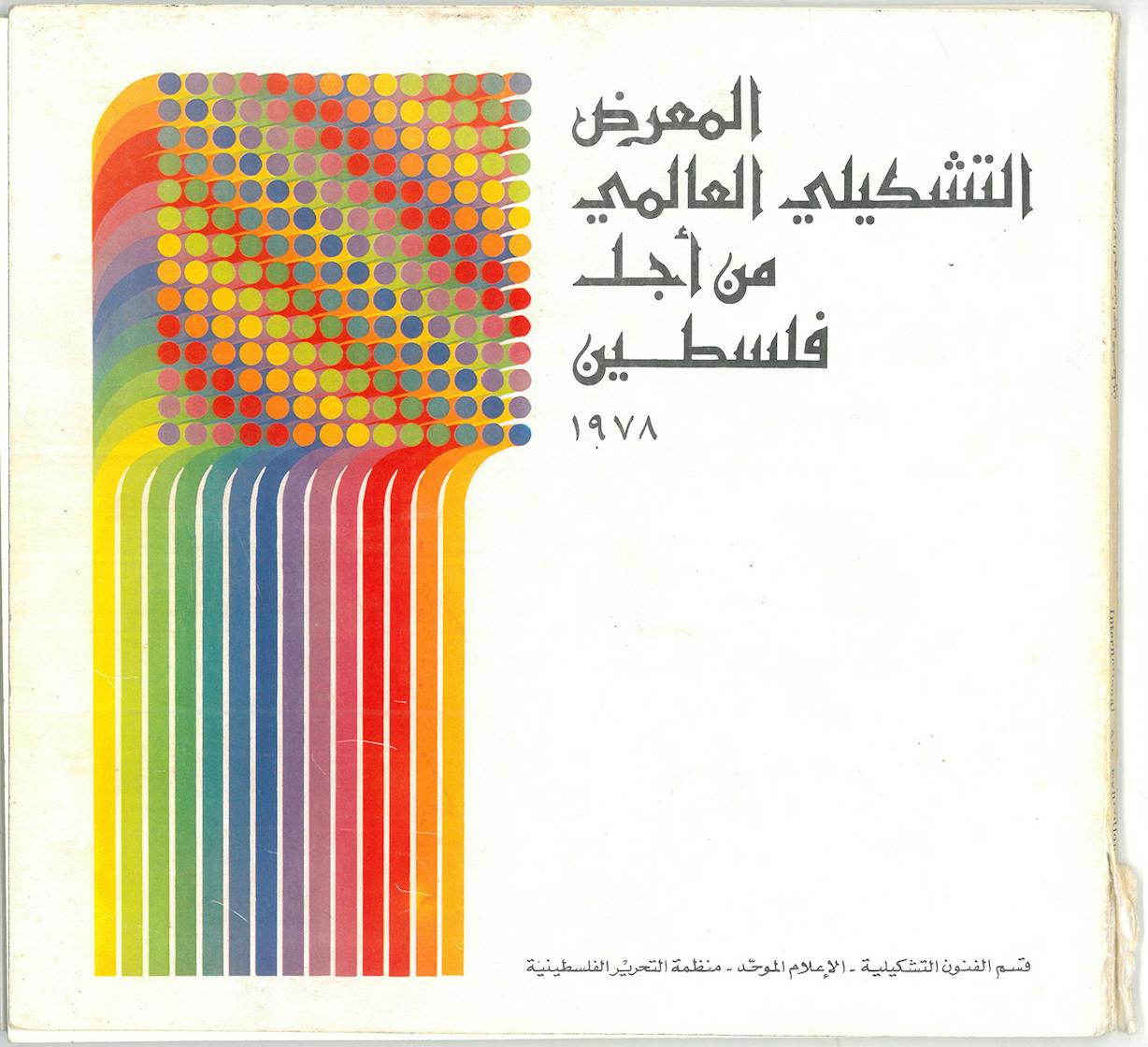

The research project Past Disquiet began in 2008 when we came across the catalogue for the International Art Exhibition for Palestine in the library of an art gallery in Beirut. As we paged through the catalogue, we were befuddled. Almost 200 artists from 30 different countries had donated artworks to the exhibition which, as the main text of the catalogue (authored by the late Jordanian artist Mona Saudi) explained, were intended as the seed collection for a future museum in solidarity with Palestine.

Covers of the bilingual catalogue (Arabic and English) for the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, Beirut 1978. Cover artwork by Julio LeParc.

Organised by the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) through the Plastic Arts Section of its Office of Unified Information, the exhibition was inaugurated in the basement hall of the Beirut Arab University on 21 March 1978, three years into the Civil War in Lebanon and a mere two weeks after the Israeli invasion of south Lebanon. The director of the Plastic Arts Section was Mona Saudi. There had been no mention of the exhibition in local, regional, or international art-historical texts, so the catalogue became our inexhaustible source of clues: the names of people thanked, the list of artists, and the images of the artworks. We tracked down each of one.

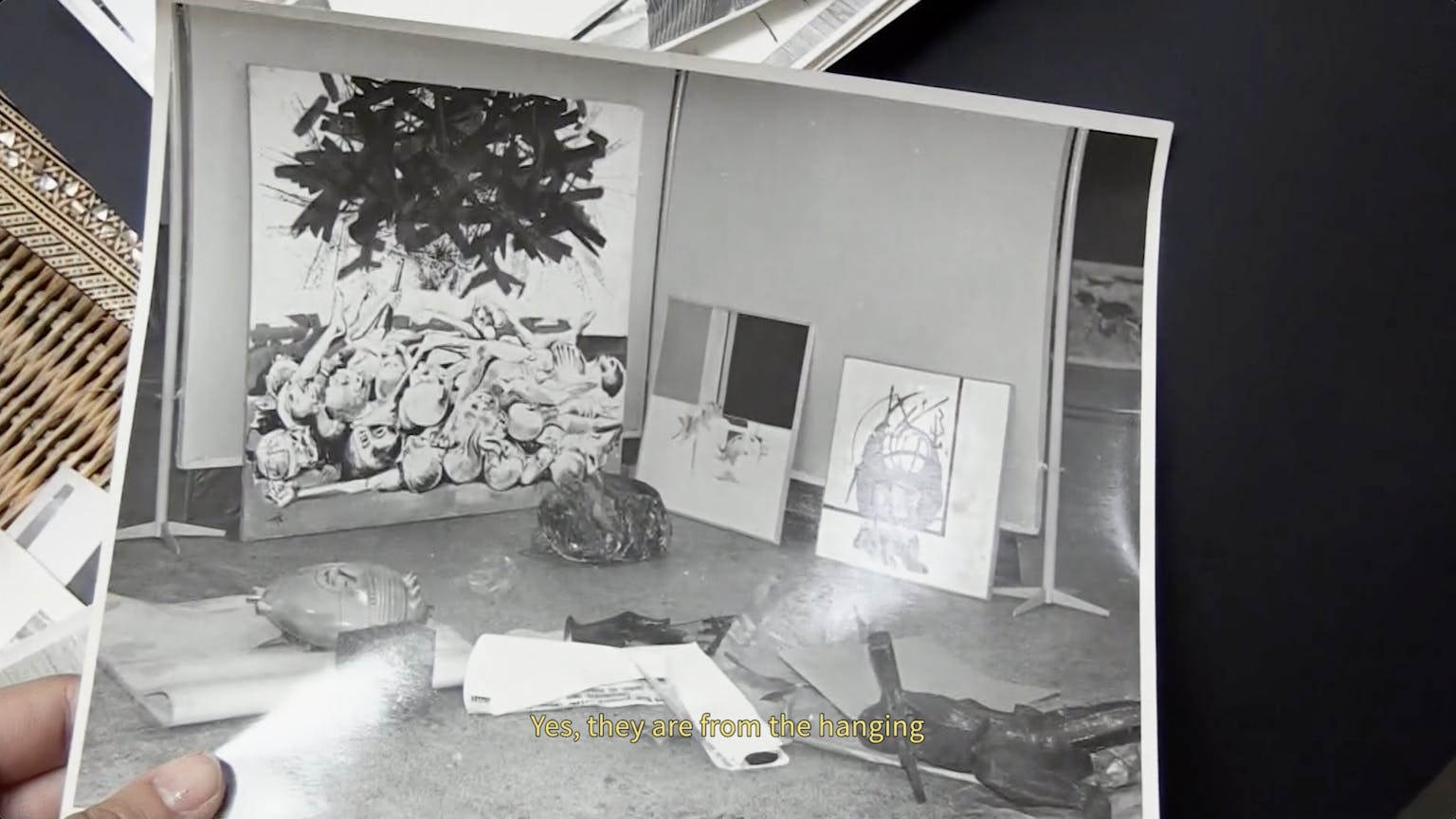

The progress of our research changed dramatically when in May 2011 we met Claude Lazar, a French artist who lives in Paris and who had been close to Palestinian militants in Paris during the 1970s. He was listed in the acknowledgements page of the catalogue and had given a work to the show. When we visited Lazar’s studio, he had pulled out three boxes from his personal archives: one containing photographs; a second containing newspaper and magazine clippings; and a third containing facsimiles of tracts, reports, and papers related to the exhibition and his visit to Lebanon.

Still from interview with Claude Lazar, 2011, Paris.

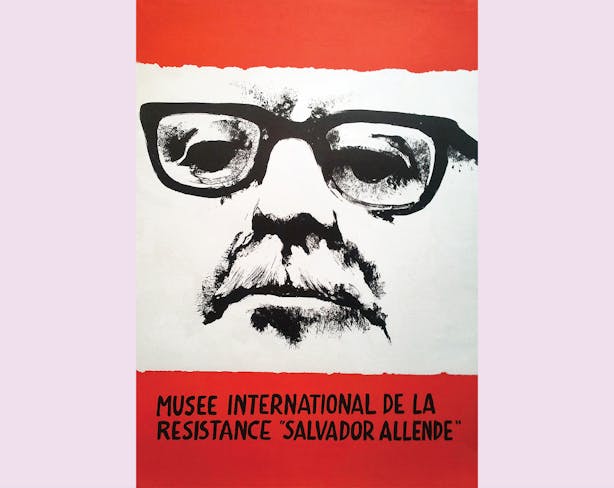

In our conversation with him, we understood that he had been a key protagonist in imagining the 1978 exhibition as a cornerstone for a museum-in-exile. He attributed the idea of the exhibition serving as the start of a collection to his knowledge of the Museo Internacional de la Resistencia Salvador Allende (MIRSA) project. Lazar had been invited to donate a work for that collection, and proposed to his close friend Ezzedine Kalak (the PLO’s representative in Paris at the time) to launch a similar initiative in solidarity with the struggle of the Palestinian people. Lazar and Kalak met with Chilean exiles at an event organised by Politique Hebdo. Lazar recalled that there was also a plan for international exhibition for Palestine already underway in Beirut, and so the two initiatives fused towards the idea of donations to a seed collection and a future museum in solidarity.

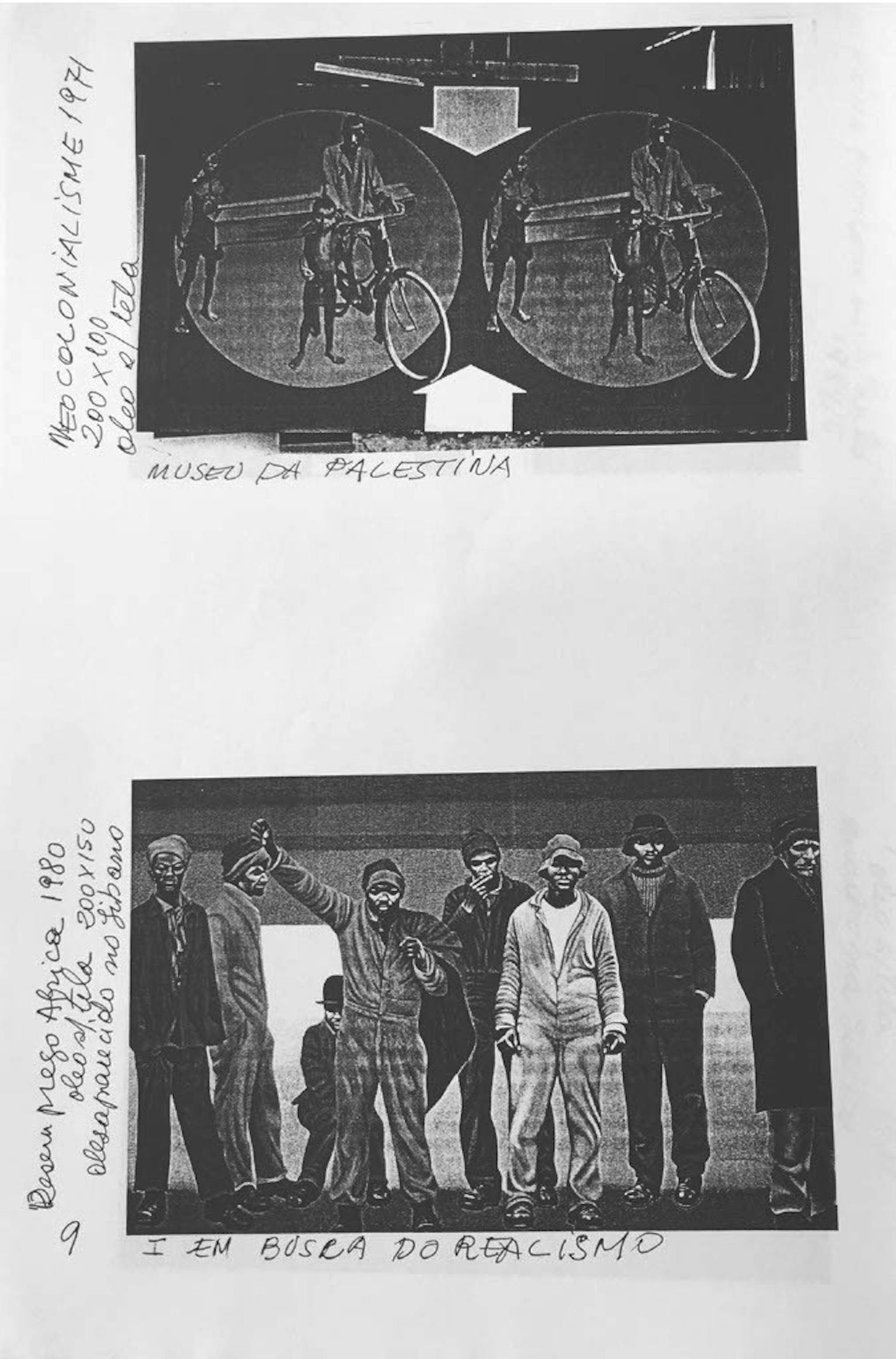

Documentation of Gontran Guanes Netto’s contribution to the collection. Courtesy of Pedro Netto.

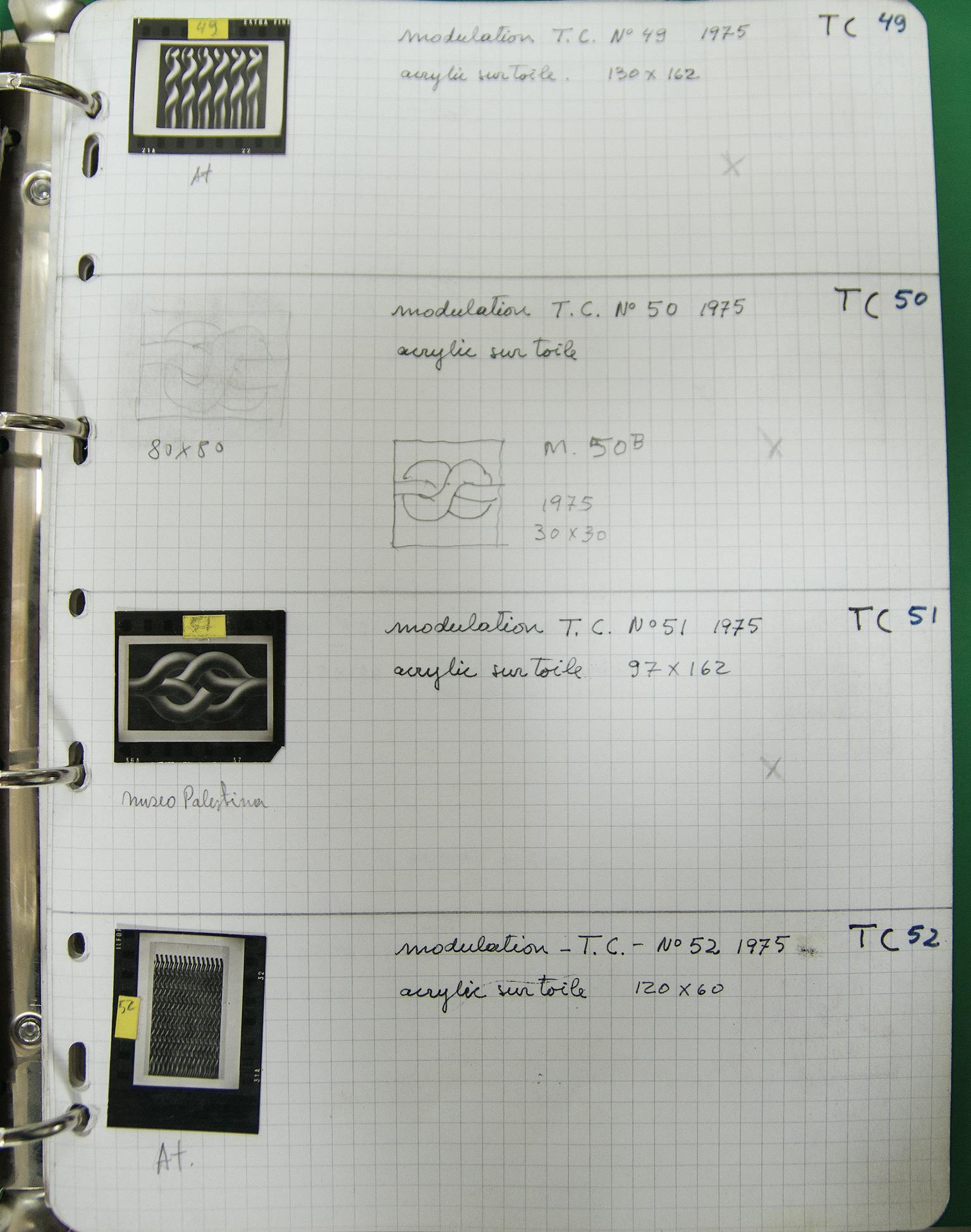

Documentation of Julio Le Parc’s contribution to the collection. Courtesy of Atelier Le Parc.

Claude also mobilised many artists living in France to donate work to the exhibition who were involved in the Salon de la Jeune Peinture – many were exiles from South and Central America and were members of the Association de la Jeune Peinture through collectives. One of them was Argentinian artist Julio LeParc – it was through our interview with him and Gontran Netto, a Brazilian artist also living in exile in Paris, that we learned about their participation in the exhibition for Palestine and MIRSA but also two other collections: the Art Contre/Against Apartheid and a collection assembled in support of Nicaragua after the Sandinista revolution. We had been unaware of those two collections, but Le Parc and Netto had contributed to all four of the collections. From the overlap of artists between these initiatives we drew a map of networks of politically engaged artists.

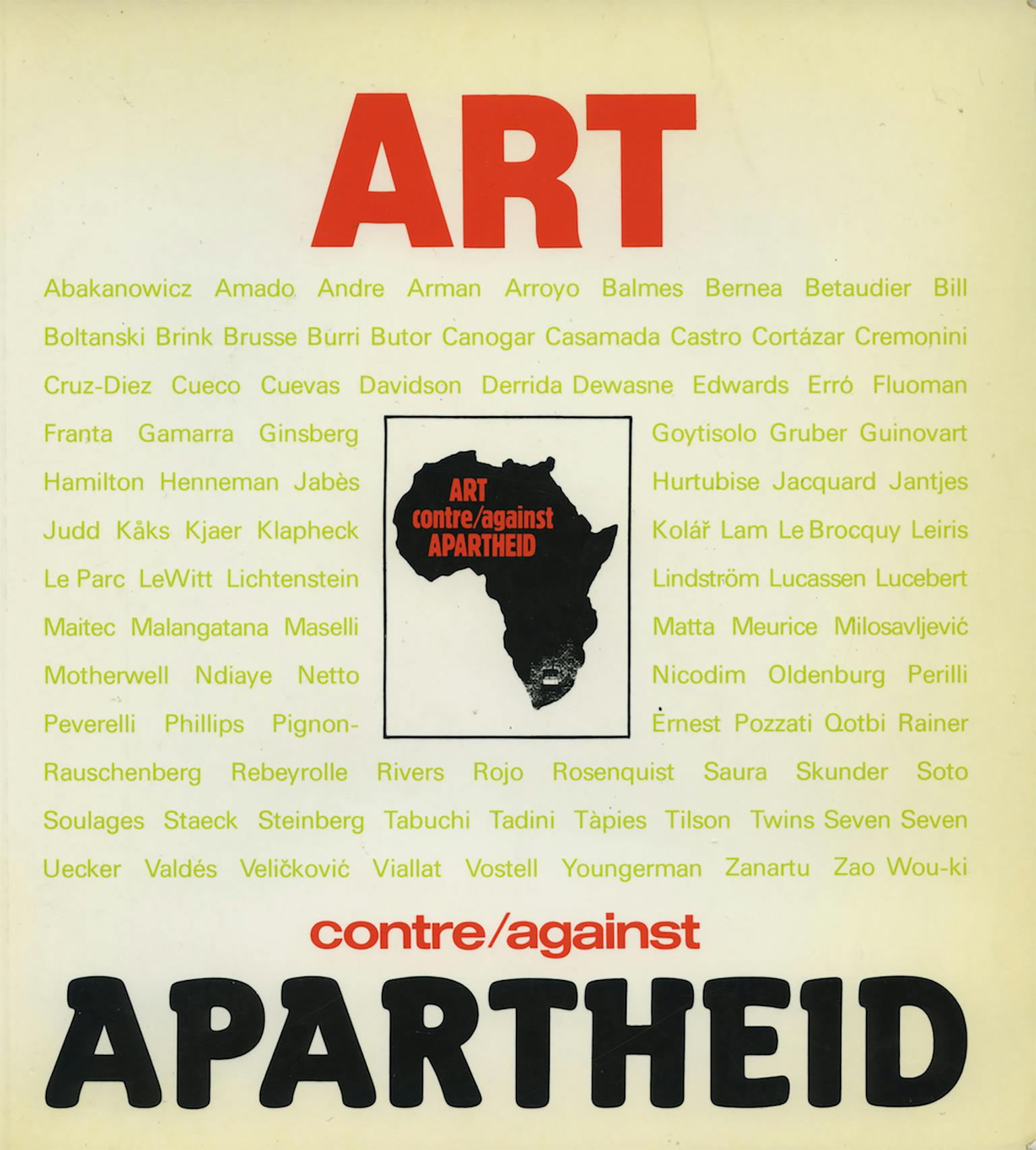

Cover of the catalogue for Art Contre/Against Apartheid, 1983.

Ernest Pignon-Ernest, a French artist who had donated works to the collections in solidarity with the Chileans, the Palestinians, and Nicaraguans, was the initiator of the Art Contre/Against Apartheid initiatives, borrowing the idea of an itinerant art collection (also referred to as a ‘museum in exile') exhibited in different places across the world to mobilise political support, in this case for the anti-apartheid movement. The Art contre/against Apartheid collection was first shown in 1981, after the International Art Exhibition for Palestine (1978), and MIRSA (1975), and in the same year as Art pour le peuple du Nicaragua (1981), the start of the Museo de Arte Latino Americano en Solidaridad con Nicaragua.

MIRSA collaborators during the inauguration of the exhibition in Avignon, July 1977. From left to right (identified): Julio Cortázar, Pilar Fontecilla, Dominique Taddei, Isabel Ropert, Miria Contreras, and Carmen Waugh, Jack Lang, Aníbal Palma, and Monique Buczynski. Courtesy of MIRSA Archives.

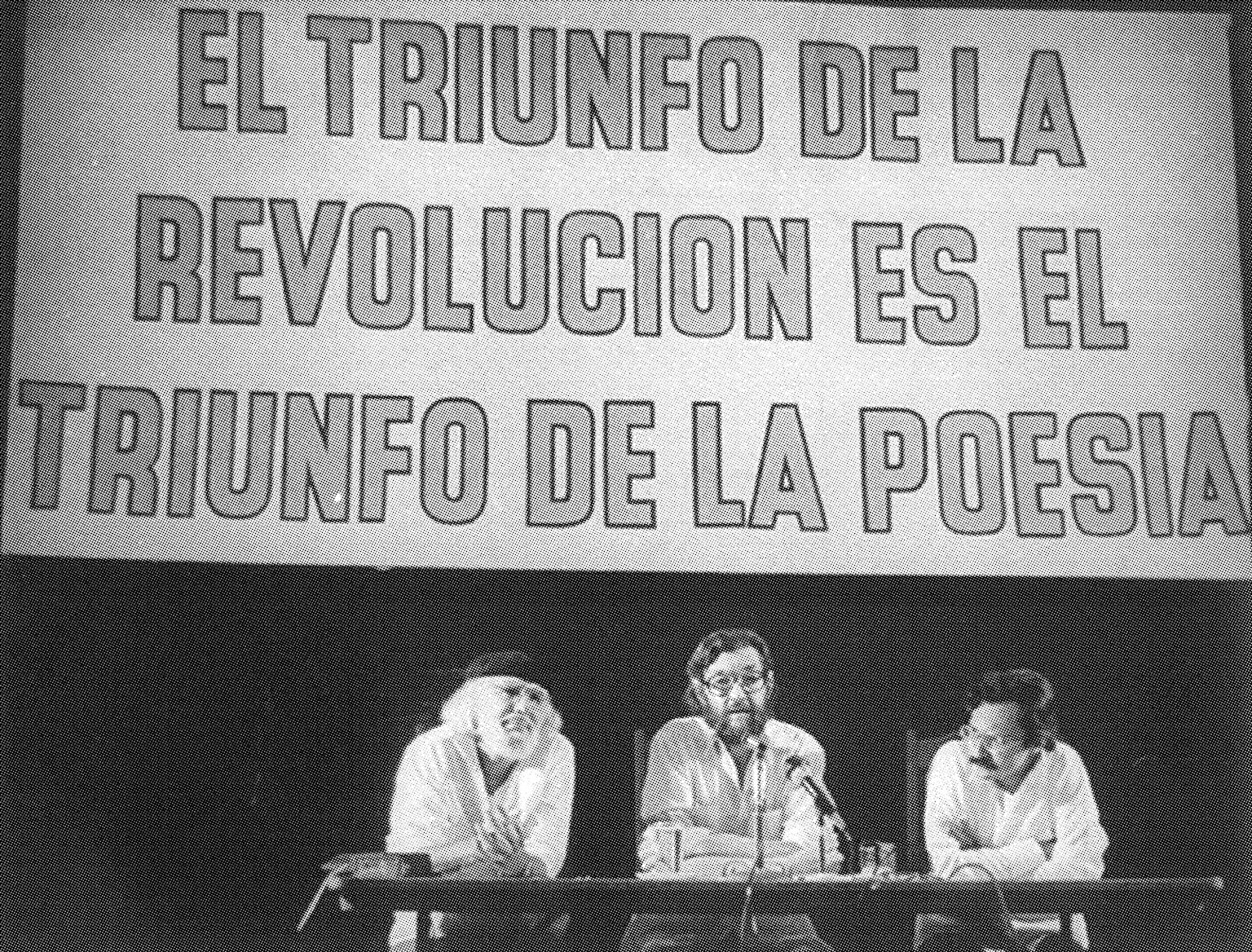

In solidarity with the people of Nicaragua after the success of the Sandinista revolution, the Museum of Latin American Art in Solidarity with Nicaragua was organised by Ernesto Cardenal (at the time the Nicaraguan minister of culture) and Chilean curator Carmen Waugh, who was a gallerist and arts administrator who had played a key role in establishing the MIRSA while she was in exile. The works were first exhibited in the exhibition Art pour le peuple du Nicaragua at the Musée d’Art et d’Essai, at the Palais de Tokyo in 1981, which collected artworks from Latin American artists living in France in solidarity with the people of Nicaragua. In 1991 Waugh became the director of the Museum of Solidarity with Salvador Allende (MSSA), after Chile’s return to democracy and the return of various collections assembled in exile in support of the overthrow of the military dictatorship. Waugh and Cardenal had met during a festival in Rome in 1980 celebrating the first year of the anniversary of the Sandinista revolution.

‘The triumph of the revolution is the triumph of poetry.’ Seated L-R: Ernesto Cardenal, Julio Cortázar, Julio Valle-Castillo, c. 1980–83, Managua. Courtesy of Julio Valle-Castilo and Matías Salvador Villa Juica.

Several countries in Central and South America were ruled by military dictators or civilian autocrats who prohibited basic freedoms and instituted stark social and economic disparity. Their governments served the interests of extractive and exploitative multinational corporations based in the US or Europe. As a result, dissenting artists, intellectuals, and militants had to flee persecution. Many found a haven in Western and Eastern Europe. They were instrumental in the local solidarity movements where they made a new home. There was also another place where Latin American exiles met, exchanged ideas, and discovered each other’s work: namely, in Havana, at the behest of the Casa de las Américas. Founded first as a publishing house in 1959, the Casa de las Américas grew to become a cultural centre a few years later. Its mission was to strengthen ties between Latin America, the Caribbean, and the rest of the world. The organisation was founded and headed by Haydée Santamaria. The annual encounters of artists, writers, poets, and filmmakers were especially inspiring and bolstered bonds that would have otherwise never existed. For the exiled Latin American artists in Europe, these encounters empowered them to create associations in their countries of exile. It was in Havana that Ernesto Cardenal – the Nicaraguan defrocked priest, poet and prominent militant in the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (Sandinista National Liberation Front) – first learned about MIRSA.

A discursive programme by Kristine Khouri and Rasha Salti

A discursive programme by Kristine Khouri and Rasha Salti

Radha D’Souza, Rasha Salti, Anne Barlow