- Mission Statement

Assembly

David Velasco et al.

Mission Statement 00: Why Now?

This is a lightly edited transcript of the seventh session of Ibraaz Mission Gathering 00: Why Now? which took place on 21–22 February 2025.

Panellists: Radha D’Souza, Rasha Salti, Anne Barlow

Moderator: Stephanie Bailey

Stephanie Bailey: We’ve made it to our final roundtable ahead of closing remarks from Françoise Vergès. We’re going to go straight into exploring what it means to measure relevance and success in the context of artistic and cultural initiatives – such as Ibraaz or a project like Past Disquiet, which Rasha will talk about, or the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC), which Radha will talk about – and how these compare to existing institutional paradigms.

The theme of this roundtable – and I’m pretty sure no one wants to hear the terms KPI and ROI – is what does success look like? How to measure it? How to define it?

Ahead of the talk, I sent specific prompts to each speaker, so I’ll introduce them this way, starting with Radha.

Radha, could you talk about how the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes came about, how it was staged, how it evolved, and how it has acted in the world as a bridge from arts and culture to law? What would you say have been your key measures of relevance and success for the CICC project? How do they match up with the measures you have observed in terms of institutions and organisations you have worked with as a lawyer, activist, and educator, ranging from the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science to climate activist groups?

Radha D’Souza: The Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes, which I shall refer to as the CICC, is an art project that I co-founded with Jonas Staal, who you heard speak yesterday. So far, we have had several iterations of the CICC in the Netherlands and other places. Before I respond to your questions, I would like to frame this conversation around certain key points for reflection. How do we measure success? Measurement is a hugely problematic thing, especially in our world today, because everything must be measured to be valued. Nothing has value if you cannot measure it.

Measurement, to me, happens at three levels. I am not speaking of hierarchical levels; rather I see the levels of measurement as concentric circles. They are interrelated. If one circle collapses, an entire zone of measurement is lost. Yet, each circle within a concentric circle is distinct. Measurement means different things within each circle.

The first circle is the existential one. We all need to exist as artists, as writers, as institutions. At this level, there is a deep tension between the big, radical ideas that we have and the particular decisions and compromises we are often called upon to make to realise the big ideas. Art institutions may say, ‘we don’t want this or that part of the project’. Money is a perennial problem. There are grant applications to be made, footfalls to be measured. All of us are familiar with such issues.

We live in a capitalist, imperialist, ecocidal, genocidal world. This world draws us into playing the game by its rules. This world was given to us when we came into it. We did not choose to be in such a society. We cannot escape it, yet we cannot accept it either. At the existential level, there is a tension between what is acceptable and what is open to negotiations. Navigating this tension is a real problem. How we navigate this tension, and how many of our core ideas and values we retain and what we lose in the process, are the measures of success or failure at this level.

The next circle, I shall call the social circle. All art is about engaging with society. Within this circle we deal with our communities: the social organisations, networks, and groups that we wish to speak to through the medium of art. Yesterday we had a good discussion on ‘who is our audience and who is our community’. We heard Ibrahim [Mahama] talk about his community and how he works with them. This question is closely related to the question about our core values and ideas and imaginaries. What do we want our art to do in the world? At this level, measurement is not about me as an artist or writer, and whether I can pull off a successful project. At this level, measurement is about my relationship as an artist or writer to others, to my community. Some of them may be artists, others may not. It is about the wider community. How does that community respond to my work? Is it relevant to them at all? At the social level, measurement is about assessing the relevance of our work for the wider community of which we are members as artists, writers, and thinkers.

Then there is a third level, which I call the level of my muse, my creator – I do not have a word for it. I would like to use the word ‘ontological’, but that sounds like a big word. This something is about the wider questions of our times. At this level, this is about our inner self, the wellsprings of our art. It feeds off the second level, and its flourishing depends at least to some extent on the negotiations we were able to make at the first level and the inspiration we get from our communities. In our concrete situation, the wider questions for us are thrown at us by the ecocidal, genocidal, imperialist, patriarchal world. How do we respond to those questions? At that level, our work will be measured by the future.

Those are the three levels or circles within which we need to think about measurement, because measurement is about a yardstick, and each circle is measured by a different yardstick. Are you able to pay your bills? Are you able to respond to the needs of the wider community at the social level? Do people care? Do they come? Do they want to talk to us? And then at the higher level, of course, there are problems in the world: how am I going to respond? As intellectuals, artists, writers, academics, we have an obligation to give something back to the society that has created and nurtured us. Measurement is about how we engage with questions within each level of assessment.

How did we handle these types of questions in the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes? The CICC came out of conversations that started with my book, What’s Wrong with Rights? (2018). I did not write the book because I was going to make an art project out of it. I had been an activist for a long time. I found that people were getting stuck in their thinking about social change. We were working hard and doing a lot of good work on our economic and political campaigns. But fundamentally, I was concerned about why we were getting stuck. Why is it that with every campaign we go back to where we started? One of the reasons, I felt, was that the way people understood and imagined the law was hugely problematic. And that is why I wrote the book for social movements, for activists, for critical thinkers who want to change things in the world. The book is about our legal imaginaries. It is not about international law or national law. It’s about how we think about the law. Because the project responded to something in society and the larger community that I work with, I think things fell into place for a lot of people. This is the third circle, my motivations to write the book, but it was closely related to the second one.

I did not plan to do an art project based on the book. That came from my ‘community’, my engagement with people. Jonas, who is also an activist and a visual artist, is from my community. The book answered, for him, many questions that he had had and struggled with. He said we should do an art project based on the ideas in the book. We talked about putting the law on trial. At this level, all sorts of serendipitous things happen. This level is a moment of excitement and creativity. Now that we had a great idea, we had to do it, execute it. That is where the existential problems begin. You need money, art spaces, you need partners, and you need to survive. You need to start making decisions.

We were lucky, but it was not just luck. At the social level, we had good relationships with our communities and good responses to what we proposed. There would not have been a CICC without an art space like Framer Framed, because they are not just any other art space. They are a socially engaged and committed art space. This is what I call the existential level. But it feeds off the second and third circles of measurement.

Again, at the second level of the society, we found amazing people everywhere as our witnesses, many of whom we had worked with in the past in other capacities. We never went for experts; we never went for famous people. It is not that we exclude them – we do not have a policy on excluding famous people. If they believe in what we believe in, great. What we always look for is fellow travellers; we value the communities we work with. We don’t want to work with just anybody. At this level, we were inspired by level three, which translated into the existential level. We were very clear: if we cannot host the CICC in Germany, because we cannot say the things we want to say in the present environment created by Gaza, so be it. It is not the end of the world. Others in other places want to host the CICC precisely for those reasons, because of our stand on issues like Gaza. We can do a CICC iteration in South Africa. The world is a big place.

Every iteration we do speaks to the local context. This is our level two commitment to our communities. When we did the CICC in South Korea, the context there was completely different from the first iteration in Amsterdam. In the Korean context, we thought militarism was a serious problem because it has hovered over the Korean peninsula for more than 70 years now. We focused on Korean corporations, companies, and the Korean state, and how they create and establish this military-industrial complex that keeps the people in constant tension, so to speak. All wars are extinction wars – extinction of ecologies and communities – that was the project’s main message. People responded enthusiastically because we were articulating their problems. If I had to do something in India, in the Indian context, I would want to put [Gautam] Adani and [Mukesh] Ambani on trial. But if I cannot do that, then we will not do a CICC iteration in India.

When we live in a bourgeois society, we are trained to think about what we want. We are not trained to think about what we do not want. I think what we do not want is as important as what we want. A lot of the time we start thinking, should I go there? Should I make compromises? Should I do this? Should I do that? But when you know what you do not want, your red lines are very clear. We do not take money from Shell. End of story. We do not compromise on Palestine. No is no. There is no negotiation. So, when you have those red lines of what you will not do, decision-making becomes a lot easier.

That is why I say: this liberal language of ‘inclusivity’ this and that, is misleading. It leads you to believe you can include everyone, that any exclusion is bad. We want people to travel the road with us, we want to hold hands, we want to walk the path. Without that there is no social change, nothing can happen. At the same time, nothing will change if you have compromised every step of the way. If you have no red lines. Having red lines does not mean you should not be flexible, because you still must pay your bills, do projects, make the existential-level decisions. Those negotiations at the existential level cannot happen if you do not have clarity about your values and vision for a better world at the third level and if your work is not in solidarity with your communities at the social level.

At a personal level, there are four Radhas. There is the barrister Radha; there is the dreamer-fantasiser Radha, and she is very much still there, not subsumed by the barrister yet; there is the social activist Radha; and there is the Radha from a specific culture and tradition, the one that my grandparents, my ancestors produced, that forms my heritage. These Radhas start a conversation with each other, let us say, about who to partner with in a project. The dreamer says: ‘We cannot work with people like that’, the barrister says, ‘Do you want to do this project, or not? Make a decision.’ You make that decision and the ancestor whispers, ‘Don’t go there, my child.’

These are the kinds of decision-making processes that have driven the CICC. But the main factor in the project is the partnership with Jonas. That partnership did not come about because I am a lawyer, or because we are doing the ‘interdisciplinary work’ that is much talked about these days. It was not the desire to do interdisciplinary work for the sake of it that brought us together. Both of us are activists. That is how we met – we were in the Kurdish solidarity movements together. We had shared values and a shared vision for the world. When my book came out, he knew where I was coming from, and that is how conversations about the project started. Would I have done the CICC project if I had not found Jonas? I don’t know. No one knows the future, or what might or might not happen. Life is too big, history is a large canvas, and we must learn to just walk – and I walk – whatever path is available to me. That is not quite about institution building, but when you walk, you will see a lot of things along the way. And you learn to respond to those things and start setting up milestones. The amazing thing about walking is that you find new things, always. You will find Framer Framed, you will find Stephanie, and through her find Ibraaz – you will find all kinds of people. This is what I hope to do, keep walking and taking in everything I see along the way.

Stephanie Bailey: It’s so interesting because listening to you reminded me of Ibrahim [Mahama] and farid [rakun], thinking about growing from the ground up effectively, and then yesterday, the Otolith Group speaking about ‘spora’ rather than diaspora, thinking about seeds and this idea of growth. That’s a very good way to bring in Rasha, who I’ve asked to talk about Past Disquiet, which is a massive and ongoing research project that Rasha has led with Kristine Khouri, and which launched with its first show at the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) in 2015.

Rasha, I wanted to ask you how you measure the project’s relevance and success, and how those measures have evolved since you started working on it?

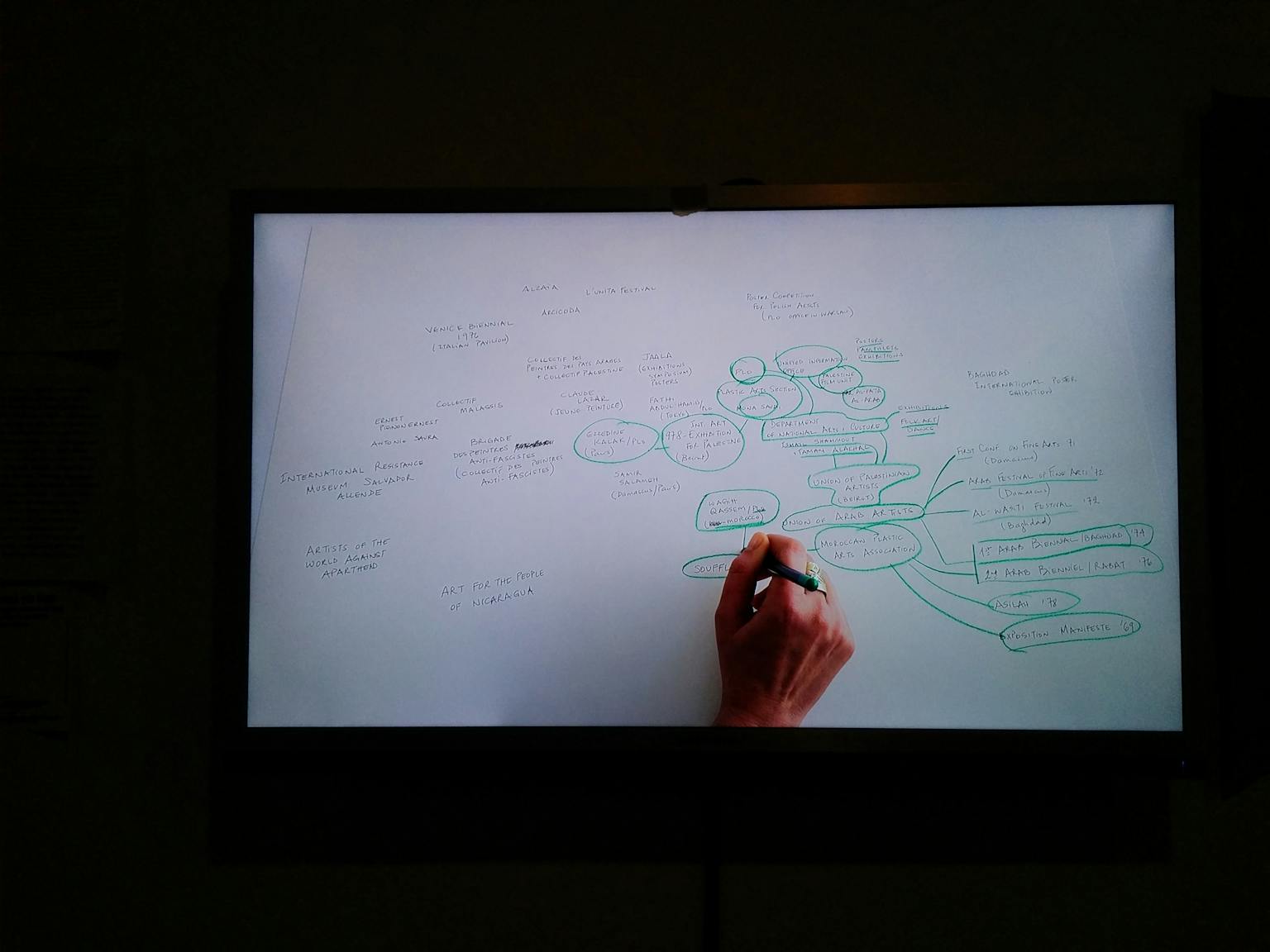

Rasha Salti: The research started in 2009. Kristine and I fell, by pure coincidence, upon the catalogue of an exhibition that took place in Beirut in 1978 that was organised by the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and was intended as the seed collection for a museum in solidarity with the Palestinian people, featuring approximately 200 artworks donated by 200 artists from 30 different countries. There was no record of this exhibition anywhere, so we decided to investigate it, and the end result is Past Disquiet.

Past Disquiet is a documentary exhibition. It does not include artworks. It’s made of archives, and yet not a single original archive, and that’s intentional. As we investigated the 1978 exhibition, we realised that the story of this collection of artworks in solidarity with Palestine was connected to three other collections, namely the museum in solidarity with the people of Chile and their struggle against the Pinochet dictatorship; the collection in solidarity with the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa; and the collection in solidarity with the people of Nicaragua after the Sandinista revolution seized power.

When we started our research in 2009, we didn’t know that the findings were going to be presented in the form of an exhibition. So, speaking of relevance, let’s just say that back then it interested no one until Bartomeu Marí, then director of MACBA, contacted us in 2013 and proposed that we consider the exhibition format. Then we got a grant and somehow the question of the relevance of the research became irrelevant – we were engrossed. Furthermore, Kristine and I have compulsive temperaments, so we dove into the research, collecting bits and pieces of history and anecdotes. The exhibition tells the story of how each of the four collections came about. Each story is told in a video. Around the video, or that story, we tell other stories about the artists and militants who made these collections possible.

Exhibition views from Past Disquiet, Sursock Museum, Beirut, 2018. Photo: Christopher Baaklini.

Exhibition views from Past Disquiet, Sursock Museum, Beirut, 2018. Photo: Christopher Baaklini.

What is a museum in solidarity? It’s a museum that comprises artworks that were donated by artists as a political act to incarnate their support for a cause. In this case, for Palestine, for democracy in Chile, for the Sandinista revolution, and for a South Africa free of apartheid. The way we think of the exhibition’s dramaturgy or scenography is that these four stories are like trees, and the other histories around them are like the soil or ecosystem in which these trees grow. In other words, the logic is rhizomatic. The first edition of the exhibition was at MACBA in 2015; the second in Berlin at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in 2016; then in 2018 in Santiago at Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende and in Beirut at Sursock Museum; then in Cape Town at the Zeitz MOCAA in 2023; and in Paris at the Palais de Tokyo in 2024. Now, we’re installing at Framer Framed in Amsterdam.

The title, Past Disquiet (or Dhikir Qaleq), is a play on words in Arabic, because one of the main characters in the research around the Palestinian story was called Ezzedine Kalak, he was the PLO representative in Paris from 1973 to 1978. His name really encapsulates the story of modernity in Arabic: ‘Ezz’ means glory, ‘dine’ is religion, Qalaq (or Kalak) is anxiety, disquietude. In the first iteration of the exhibition, we gave him a significant space. We had to make space for other characters in subsequent editions. Invariably, people ask us why we use ‘disquiet’ – it’s unusual. We borrowed it from Fernando Pessoa’s Le Livre de l'intranquillité, which is translated in English as The Book of Disquiet.

So why ‘disquiet’? When we were interviewing the people who made these collections possible, we realised they were, for the most part, artists who did not matter to the market, and consequently, they had been written out of art history. They were in their 70s, 80s, and sometimes 90s, and we were asking them to remember a time when they were very politically engaged, when they brought art to public space, created their own spaces, and created their own collections. The way people remember is very much through affect – we were bringing them back to a moment of glory. The narratives they were recalling were full of holes, anger, or frustration, and sometimes they denied others were there and played equally important roles. It’s what happens when you’re trying to surface a history that has not yet been written and that’s full of wounds and full of holes. That’s why it’s ‘disquiet’.

Every time we show the exhibition, we try to unearth the local links to the histories. Right now, the new edition we are installing at Framer Framed has been augmented with the research we conducted in Amsterdam with support from the Framer Framed team. We discovered that solidarity movements in the Netherlands were next level. In other words, what we resurrect through our research is a past that refuses to sleep, a past that refuses to lie down, a past that refuses to be forgotten and which is often troublesome.

How do we measure success? We don’t, and it doesn’t matter. Firstly, I don’t know how you measure success. When we applied for grants, more often than not, we were rejected. It’s important to follow your intuition, your heart, and to dare to be anachronistic. What is deemed timely now is set by fascists, by the market. It was important for us to take our time. It’s counterintuitive that we should be organising the seventh edition of Past Disquiet, right? But the exhibition is still evolving, and institutions continue to invite us. We’re still surprised about that.

I try to quote as few white men as possible, but Jean-Luc Godard said: ‘The margin is what holds the page.’ We never aspired to be canon making, but we know that the work we do in the margins is vital.

Stephanie Bailey: Listening to Rasha and yourself speak, what I’m hearing is that measuring relevance and success has to do with people. So, Framer Framed transformed your experience, or it transformed your perspective, and it was MACBA, in fact, that launched the project as an exhibition in 2015.

Rasha Salti: Bartomeu Marí was interested in exhibition histories from the Global South, and he assigned a star curator, Paul Preciado, to work with us. We felt blessed. The big lesson that I’ve learned working on this project is to never disregard the accident. Somehow, at some point, if you become aware of it, the research leads you and you just need to have the confidence to follow it. What I want to say plainly is that we felt that we were led by ghosts, we were helped by ghosts. There have been so many accidents, coincidences, serendipitous moments that it became ridiculous to keep ignoring the fact of their happening. There was a reason.

Stephanie Bailey: Were there any measures you had to take to protect the project in any way, just out of curiosity? Because as with the CICC, you have been exposed to or you have engaged with so many different bodies, in the context of so many different institutional mainframes, let’s say.

Rasha Salti: We are dealing with materials, images, text, footage that survived the ideological political moment when it was produced. So it was always crucial to think historically. For example, there’s a photo of a Palestinian freedom fighter with a Kalashnikov looking at a painting of a Kalashnikov in a courtyard in Beirut. The photo is maybe 20 centimetres long, but in Berlin we didn’t want to include it and have the German audience lecture us about armed struggle and violence. We could place a caption, but we were not sure whether anyone would bother reading it, and we were worried that this photo could overwhelm everything and we could be accused of celebrating violence. In Beirut, of course, the photo was huge, floor to ceiling.

Stephanie Bailey: Anne, you’ve worked in New York, running Art in General from 2007 to 2016 and overseeing an incredible range of projects before moving on to Tate St Ives in 2017, where you are now. I wonder if you could talk about the measures of relevance and success you have encountered in these different contexts and how they’ve measured up to your own criteria? Also, have there been any projects in particular that you’ve worked on that sharpened your own measures?

Anne Barlow: At Art in General we had several core programmes, but I wanted to mention those that I would say particularly sharpened our thinking and operations over the years that I was involved with the organisation. Art in General was a small nonprofit that was very artist-centred, with a specific remit to support the development of new work that would otherwise not necessarily be supported by larger museums at that stage of an emerging artist’s practice, or within a commercial context.

Collaborating was a core part of our remit, first and foremost with artists. We would sometimes work with artists over several years in order to realise their projects, which could be in any medium or form, depending on what they were interested in producing. Collaboration with institutions was another main strand, and we worked with multiple small- to mid-sized nonprofits in different parts of the world. A key programme was the so-called Eastern European Residency Exchange (EERE) programme that involved sustained, multi-year dialogue between Art in General and institutions in that wider region. What that enabled us to do was to plan artist residency exchanges across our organisations in ways that had deeper purpose and meaning. It also gave us a much deeper insight into our respective infrastructures in terms of mission, governance, and finances. We all learned a lot through those dialogues over multiple years and found that to be a very enriching experience

By 2012, in response to shifting sociopolitical contexts, and in the area of artist residencies and art networks more broadly, it felt necessary to reassess the programme model. Allegiances such as this, based on real relationships and trust, enabled us to collectively provoke and interrogate the structures of the EERE programme. This was something I wanted to raise because it triggered a deep analysis of what we were doing and why, how we were collaborating, and the different challenges that each one of us might face.

At the same time, a chance encounter brought something beautiful into our lives. A planned visit by Art in General to the Cairo-based organisation Beirut, whose work we found inspiring, was delayed multiple times for various reasons, and we ended up visiting at a time when several other small nonprofits from around the world were gathering in Cairo. We ended up talking intensively for two to three days about institutional identity and purpose, using Cairo as the point of departure – we didn’t want the conversations to end. This accidental meeting led to the formation of a group called ‘April’ – the month we all met – that comprised Beirut, Art in General, Kunsthalle Lissabon, CCA Derry–Londonderry, which later shifted to the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, and FormContent in London. I felt this group could be of interest for Ibraaz in terms of all the amazing conversations we’ve been having across the last couple of days about what it means to form an institution now.

A core goal of April was to take valuable time out of production-focused activities, to question how institutions like our own could continue to evolve and change, and how working or thinking together might open up new possibilities. Our first joint endeavour was to write for the summer 2013 quarterly of ArteEast, as part of an editorial framed by Beirut, which posed the questions:

What is it to build an institution as a curatorial act? Can an institution evolve using the language and logics of art practice? If social and political imagination is a prerequisite for change, can the realm of art be imagination’s guardian, nurturer, and inspirer in a time of economic and political violence?1

As an older institution, the questions we posed to ourselves at Art in General were:

What is it to inherit an institution, with all its history, and an identity that exists at a given moment, but that is just one in a longer life of histories – an organic event unfolding over time, both before and after us? How can it be reimagined, how do we shift and reflect? What values should it embody and where can we take it in the time that we are here? ... [A]s the current caretakers of this institution, how might we incorporate aspects of the ‘possible’ alongside the real? And subsequently, how do we leave the space for alternative futures, ensuring that there are pathways and directions open to those who come after us?2

In combination, the thinking across these groups led us to create What Now?, a series of symposia, the first of which was internal. That was followed by three annual symposia in collaboration with the Vera List Center for Art and Politics in New York, which brought to these discussions perspectives from art, sociology, science, philosophy, and other fields.

The first public symposium explored the topic of ‘Collaboration and Collectivity’ in terms of relationships across and among artists, institutions, and constituencies of various kinds.

Each symposium led to the content of the following one, with ‘Collaboration and Collectivity’ leading to ‘The Politics of Listening’, which examined the idea of listening as a political act, a pedagogical process, and a protocol for engagement. In turn, the topics that came out of this led to ‘On Future Identities’, which focused on constructions of the self, queer theory, self-determination, mutability, the body, technology, social media, and the ever-evolving relationship between the digital and the material. Over these three years, we also commissioned a series of projects and programmes at Art in General that reflected these wider concerns, both online and in physical space. These were incredibly important initiatives for us in terms of trying to rethink those notions of what is relevant, how as an institution you continue to evolve, and what issues are you tackling and why.

Moving to the present day, I am now based at Tate St Ives, Cornwall. A fundamental difference between these two sets of experiences is the context of place – moving from New York, a very metropolitan and diverse city, to a small post-industrial community in a rural region in England. I now find myself in a place where tourism takes over in the summertime in contrast to the spring and winter seasons that see largely local and regional visitors to the gallery. Socioeconomic deprivation is a reality in this region, as is the lack of access to infrastructures that are more prevalent in larger cities.

Tate St Ives exists because of modern artists including Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, and Naum Gabo, who moved to Cornwall at the outbreak of the Second World War. The challenge and the opportunity is to think about how you craft a programme that revisits these Modern art histories within the broader contexts of global art histories alongside bringing contemporary artists from around the world to St Ives. Artists whom we have invited to exhibit have tapped into topics and issues that are important globally but also on a local level here, including the environment, climate change, cultural identity and language, and ancient mythologies, and I’m just going to scroll through some slides that reflect how artists have delved into these various areas.

When you are living in a community, many partnerships are hyperlocal, and I was listening with great interest to other speakers in the last couple of days who were talking about the importance of working with communities, constituencies, and gatherings that already exist. In our case, this has involved working with the healthcare sector through social prescribing, access initiatives, and the Hospital Rooms project, among others, as well as more broadly with young people, schools, families and children, and community organisations in and around the town.

Looking ahead, we are currently developing a building called the Palais de Danse, which was Barbara Hepworth’s second studio and where she made some of her largest-scale works. The Palais is opposite the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden that Tate also runs, and that was Hepworth’s first studio and former home. The Palais has an important social history as a former dance hall and a cinema, and for the community it is a place that holds rich memories in terms of social gatherings and public use. What we want to do with this space is to celebrate the legacy of Hepworth in a way that emphasises her artistic process, but that also expands on this artistic legacy by using the idea of making as a way of engaging local communities and visitors through various programmes and activities. With a dance floor and stage, it also opens up performance and dance as new activities, both for artists and St Ives communities. As a building and programme, the Palais will be more of a shared space with our audiences, offering an entirely new way of working in the future.

Stephanie Bailey: Thank you, Anne. We have about 15 minutes now for questions before we give the floor to Françoise Vergès for final remarks. If you have questions or comments, please feel free, but we would also be interested to hear what would be your measures of relevance and success?

Hannah Cobb: Echoing what Declan [Colquitt] said before, thank you so much for having us here. It’s been such a privilege to be part of this incubation, and I’m really excited to see how this progresses. I was going to ask a few questions, but some of them were answered in that panel.

Is this event something that you see happening again, once the institution has opened and things are happening? I ask because what came up in this panel, for me, was that these places rely on feedback loops between the institution and the communities that they’re serving.

Lina Lazaar: It’s a very good question because we started off thinking this would be a two-day gathering in which we would figure everything out. We would be able to navigate collectively through the riddles of our time, the challenges, the complexity. The truth of the matter is there’s so much more to unpack that I think we are already starting to plan the next session.

If we were to really summarise all the questions raised in the past two days, the essential question was, can this help us create a safe space? What I live with now is the feeling that maybe there is no such thing as a safe space because of the nature of our world and the complexities, opposing agendas, and all the discrepancies of our existence.

I think that maybe it’s not a safe space that we really should be looking at, but a brave one; a space that can be brave: elegantly brave and honestly brave. That’s perhaps a better marker of success. If there’s anything that has come out of these sessions it’s probably this, because I don’t think anyone can guarantee the safety of all. I think safety has to be shared, and we rely on you as much as you rely on us for creating the conditions for safety.

Stephanie Bailey: That reminded me of what Evan [Ifekoya] said yesterday, which was that we also have to cultivate safety within ourselves so we can then be with one another in dissensus sometimes, right? I was talking to the catering team, who are students, and they were saying how these conversations have been interesting for them as well, but there’s no space to have them, and how do you find spaces like this? Zein [Majali], you were saying something similar – this question of space has really come up a lot.

David Velasco: This was a really fabulous panel. I love what you said, Lina, about a brave space, I think that’s a beautiful agenda. I loved, also, what Rasha said about how we measure success, and you said we don’t. I think that’s a great answer. I was always suspicious of metrics as a determiner of the quality of what we were doing. And when I was asked to report on numbers or anything like that, I would say to my editors: ‘How many thank-yous have you gotten from the writers? What is the quality of the emails that you’ve received? How are your relationships? What kind of feedback are you getting?’ That’s the only criteria for success that I thought mattered.

Rasha Salti: I wanted to avoid bragging. The exhibition in Amsterdam contains the outcome of research conducted for the most part at the International Institute of Social History (an incredible archive), and we could only include 30 per cent of what we uncovered. The core of the exhibition is actually from private and personal archives, from people who received us in their homes, allowed us to photograph their photographs, to read their letters, and allowed us to show their reproductions. The thank you list exceeds a hundred names – it is bewildering. The notion of authorship is also important. Kristine and I present ourselves as the authors (you hear our voices, we wrote the wall texts and captions) but we are not telling our stories; they are stories of other people, and that’s a gift, even if that gift is a little broken or contains some poison regarding another person. It doesn’t matter. It’s a gift. To us, these gifts are also measures of success.

Past Disquiet is an exhibition that shows four museums (or collections) made by refugees, political refugees, and by the people who hosted them. They didn’t host them out of charity or because Human Rights Watch was watching. They hosted them because that’s what you did back then.

Malak Helmy: I wanted to say thank you for the last two days, to everybody who spoke, but also to the respondents, because I think it’s interesting how we are thinking about a lot of keywords, like ‘trust’ and ‘humility’ and so on, and as much as I really admire everybody in the room, for me it takes quite a bit of time to trust, because our priorities are different. It’s not that I don’t respect everything, but how do you build that trust? I’m really impressed by how a lot of the comments that were said really take the invitation quite seriously, which is that the space is still malleable, and we can really think about it and can really hold it accountable. I mean, you were saying to be brave as an institution. But how do you also be brave as an audience or as a participant in the sense of saying: ‘I will tell you what I really want, and I will tell you what our differences are.’ That was interesting because I tend to sometimes take a step back, and this made me think about how we also grow as participants and take the opportunity seriously.

Nadja Argyropoulou: I was listening to this amazing panel and I thought about what it is to be between audiences and success and relevance, which is like being between a rock and a hard place. Maybe we need to rethink how we measure or understand relevance and success. And it is certainly not in numbers, and it must open up to a horizon further than the one dictated by social media.

One of the most telling experiences in this respect was how the various communities of immigrants and refugees that participated in the project Wor(th)ship, which I was previously talking about, made the story of the show part of their own stories. They incorporated the experience of this project and the images it produced into their own rituals, visuals, and storytelling. So, whatever we did was perpetuated, carried onwards through channels beyond our control as it should. For me that is the true measure of relevance and success.

Werner Binnenstein-Bachstein: I like the idea of the safe space, and of Ibraaz reinvented, also. But I also like the idea of a gift culture because we are transactional all the time and I think what you have already shown here is that you gifted us these two days. I think gift culture is maybe a bit of the other side of a programmed space, and a steered space of letting go and letting come as a gift to different audiences, exploring this and experiencing this beautiful space. Because it came up several times, the word gift, and I felt that’s a beautiful word.

Rasha Salti: This is to Lina. I would say the fundamental motive for the space should be your desire, really. The word listening came up a lot, right? Listening is what you ought to do – we will listen and we listened today. Today ‘listening’ is a synonym of hearing, but the origin of the word, ‘list’, which comes from ‘lust’ in German and Dutch is to desire. To listen is to lend yourself to the desire of the other.

David Velasco et al.

Y7

Kamel Lazaar