- Essay

Opacity as Resistance: Reversing the Image Politics of Empire

Heba Y. Amin

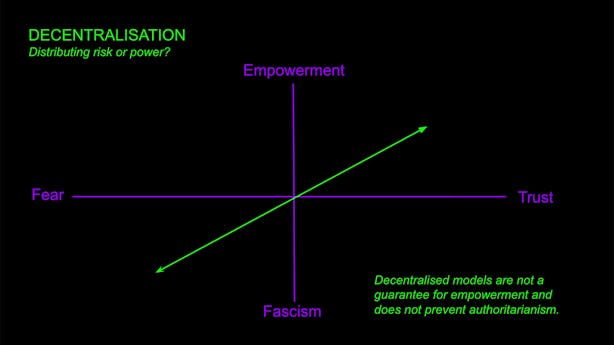

A report on the role of militaries and intelligence agencies in shaping public narratives.

Special Competitive Studies Project's Artificial Intelligence Expo, 2025. Courtesy of the author.

(24 September 2025) The continued reductive portrayal of propaganda as equivalent to the dissemination of disinformation is inexcusable and muddies public understanding of influence industries.

As noted in the scholar Paul Linebarger’s classic 1948 book Psychological Warfare: ‘Almost all good propaganda – no matter what kind – is true. It uses truth selectively.’ The essence of effective propaganda is to discover and emphasise embarrassing facts about the target as part of controlling the dominant narrative, while degrading the ability of the opponent to do the same.

Journalists often rely on sources leaking documents to expose wrongdoing. But intelligence agencies and special-operations teams can simply steal them. Indeed, civil liberties advocates frequently note that journalists are a common target of spyware.

An informed public debate regarding the special operations and intelligence agency usage of artificial intelligence–powered internet surveillance and offensive cyber technology, which are part of its influence campaigns, cannot take place without at least a basic understanding of the mechanisms.

With recent reports of the US transitioning in 2024 to the dominant home for spyware – despite public gestures towards opposing the technology – it is critical that the public expands its understanding of the role militaries and intelligence agencies play in shaping public narratives. The simplistic view of propaganda as the dissemination of disinformation was rejected by scholar-practitioners more than 75 years ago.

The public response to US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) quietly resuming its $2 million contract with the Israeli-founded spyware manufacturer Paragon Solutions at the end of August is instructive. The contract – signed with the cyber division of ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations branch on 27 September 2024 – had been put on hold in October, as a result of the outgoing Biden administration’s concerns that it may conflict with an executive order Biden signed in March 2023, which banned commercial spyware deemed to be a sufficient US national security risk.

The story has taken on a life of its own since it was first reported by the author. This is largely the result of voluminous reporting on confirmed instances of Paragon and NSO Group spyware being used against journalists and human rights activists, and so much of the subsequent focus has been on the deep ties between Paragon’s founders and Israeli intelligence. One co-founder, Ehud Schneorsen, previously commanded Israel’s primary signals intelligence agency, Unit 8200. Another co-founder, Ehud Barak, was prime minister of Israel during the turn of the century.

Paragon’s new owner, the Boca Raton–based private equity firm AE Industrial Partners, has largely escaped scrutiny, despite the firm’s operating partners including former Department of Homeland Security science and technology head Reginald Brothers and former acting DHS secretary Kevin McAleenan.

Following AE Industrial’s reported $500 million acquisition of Paragon in December 2024, roughly two months into the ICE contract freeze, the spyware firm was quickly merged into the Chantilly-based offensive cyber operations company REDLattice. More than $10 million in recent contracts between REDLattice and Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) – the US President’s most elite team of inter-service commandos – are easily found on the official US Government financial transparency website USASpending.gov.

The close relationship between the former US national security officials and Paragon had begun long before the company’s acquisition by a Florida PE firm. John Finbarr Fleming, the CIA’s former assistant director for Korea, took over as the executive chairman of the US branch of Paragon in January 2024, according to his LinkedIn profile. Following the company’s merger into REDLattice at the end of the year, Fleming became an executive vice president at the new parent.

A recent head of the CIA’s offensive cyber operations arm, Andrew G. Boyd, similarly joined REDLattice as a board member in late 2023 – additionally briefly joining the board of the parent company of competitor Boldend the subsequent year – and was additionally announced as an operating partner of AE Industrial in March 2025. This information operations arm of the CIA is most widely known as the subject of the WikiLeaks ‘Vault 7’ disclosures, which included details of the agency’s collaboration with British intelligence on hacking not only phones, but also vehicles and internet-connected televisions. The organisation received a more sympathetic portrayal in former New York Times journalist Tim Weiner’s 2025 book on the post–Cold War CIA, The Mission, where the Center for Cyber Intelligence was reported to have wiretapped the Switzerland-based Tinner family as part of a successful effort to shut down the Pakistani engineer A. Q. Khan’s for-profit nuclear exportation business.

The infamous Israeli spyware firm Candiru was similarly quietly acquired by the US special operations–affiliated investment firm Integrity Partners for roughly $30 million around the beginning of 2025, according to reporting from the Israeli technology outlet CTech. As stated on the website for the Southlake, Texas-based Integrity Partners: ‘We lead with our proprietary Special Operations Methodology. An approach we developed from deep military experience in highly-trained military units.’

(The Atlantic Council concluded in a recent report that the US became the home for spyware following a wave of investments in 2024.)

Much like their close peers in the CIA, JSOC built its own hacking unit, with the act of conducting offensive cyber operations often being referred to by the euphemism of ‘computer network operations’, while the military hackers themselves are known as ‘interactive operators’. Erick Miyares, a former member of JSOC’s sensitive intelligence unit, known as Task Force Orange, recently completed his dissertation on the cyberpsychology aspects of such work, including the long-term impacts on the operators themselves. Bill Wall, the head of the government services division of the Manhattan-based information operations contractor Accrete, is described on the company’s website as ‘the founder and first commander of a unique computer network operations organization in the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC)’.

Former US National Security Agency director Paul M. Nakasone, a board member of the San Francisco–based artificial intelligence company OpenAI, was announced as an advisor to Accrete in late August. As exposed last year by the author through a trove of leaked corporate slide decks, Accrete has been a close partner of The Wire Digital, a China-focused defence contractor and media outlet run by David Barboza, a former Shanghai bureau chief for the New York Times. Nakasone was also announced as the founding director of Vanderbilt University’s Institute of National Security last May, recently leading a media campaign characterising the Chinese artificial intelligence company GoLaxy – whose name comes from its original focus on the board game Go – as an unprecedented technical tool for Chinese information operations.

As reported late last August by The Intercept, US Special Operations Command, the parent organisation of JSOC, has openly requested a contractor who could provide ‘a capability leveraging agentic Al or multi‐LLM agent systems with specialized roles to increase the scale of influence operations’. The Palo Alto–based artificial intelligence contractor Rhombus Power has similarly openly advertised its support for joint US–Philippines information operations against China, via its Ambient product, by way of a keynote on the morning of 4 June with Philippines secretary of defence Gilberto Teodoro, Jr. (Last year Reuters revealed that US Special Operations Command Pacific, under the leadership of reportedly former Delta Force commander Jonathan P. Braga, conducted a disinformation campaign against China’s Sinovac COVID-19 inoculation beginning in 2020, later admitting to ‘missteps.’)

Information operations can range from espionage – passive infiltration for the purpose of monitoring a target – to more active campaigns, such as ‘hack-and-leak’ influence operations, disinformation dissemination, and destruction of communications infrastructure. Governments also attempt to control narratives through massive advertising campaigns, as in the case of the Netanyahu administrations recent disclosure of a $45 million contract with Google and YouTube. Beyond attempting to gain public support for airstrikes against Iran, the ads denied the existence of famine in Gaza and attempted to discredit the United Nations.

Google’s own ad transparency portal has also recently exposed an ongoing Persian-language ad campaign across 19 countries – including the US and Germany – which is attempting to pay Iranian nuclear engineers to defect to Israel by accepting money from the Mossad. Two of the ads directly invite their targets to engage with the Mossad, while others promote high-paid, allegedly tax-free jobs for Persian speakers with apparently fictitious consulting firms.

Government cyber disruption campaigns have also targeted the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, and recently leaked emails from former Israeli minister Benjamin Gantz that included reference to cyber disruptions as part of a ‘Counter-BDS Initiative’, which appears to have morphed into the organisation known as Israel Cyber Shield / Keshet David (David’s Bow), the cyber arm of the widely reported Israeli propaganda initiative known as Kela Shlomo (Solomon’s Sling) / Concert / Voices of Israel. One prominent offshoot of Keshet David is the advocacy group CyberWell, which closely partners with leading US social-media companies as part of advocating for content moderation policies it describes as stemming online antisemitism.

The author has similarly procured copies of numerous contracts where JSOC and various US Special Forces groups procured the Pulse ‘tactical information warfare’ toolkit sold by the Arlington-based intelligence contractor Two Six Technologies, combining commercial mobile phone location-tracking data with social media surveillance and mass text-messaging capabilities as part of monitoring and influencing regional narratives. Two Six’s board has included former NSA director Mike McConnell – a predecessor to Nakasone – and the company has hired former CIA clandestine service chief Elizabeth Kimber as its Vice President of Intelligence Community Strategy.

The monitoring of so-called publicly available information (PAI) – a US legal term of art that pointedly avoids the ‘intelligence’ word in ‘open-source intelligence’ – has become intertwined with offensive cyber. In addition to PAI functioning as a target selection mechanism for offensive cyber, open-source monitoring can serve as cover for hacking. The author obtained access to communications from within the ‘Vulcan’ US Special Operations Command procurement network detailing how Sayari Analytics, a for-profit spin-out of the Palantir-powered, US government–backed think-tank Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS), provides the US government with its corporate records analysis platform for classified information operations and offensive cyber activities, including in partnership with the US Air Force’s 67th Cyberspace Operations Group.

With the understanding that sanctioned entities are often interesting targets for US intelligence collection, organisations that defensively help US corporations avoid doing business with sanctioned entities can – and often do – aid intelligence agencies with target generation.

Sayari has, for example, publicly contracted on the classified ‘MORTAL MINT’ US intelligence programme, which is run by the US Air Force’s Office of Competitive Activities as part of strategic competition with China. One of the only hints as to the focus of MORTAL MINT is a 2023 Pentagon budget, which notes the programme’s relationships to counter-drug activities. Another is the programme’s $54,280 procurement in October 2024 of a sanctions dataset from the German company OpenSanctions, an unofficial spin-out of the previously US government–backed investigative journalism group OCCRP.

The government services division of the London-based communications firm M+C Saatchi similarly pitched its ability to expose ‘state-sponsored criminal syndicates supplying fentanyl precursor and other drug paraphernalia to the global market’ through flyers passed out at the Special Competitive Studies Project’s 2025 Artificial Intelligence Expo.

At the 2024 AI Expo, Palantir chief executive Alex Karp argued that the US government’s ability to control narratives and suppress criticism of its foreign policy on college campuses is necessary to preserve credible threat. ‘We kind of just think these things that are happening across college campuses especially are like a side show. No, they are the show,’ Karp told the audience. ‘If we lose the debate, we will not be able to deploy any army in the West, ever', he continued.

France24 correspondent Jessica Le Masurier (left) being ejected from the main hall of former Google CEO Eric Schmidt’s AI Expo at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, DC at the behest of Palantir security analyst Taylor Campbell (right). The author was shortly temporarily ejected from the hall for capturing this image.

At the subsequent AI Expo, amid US-aligned information operations contractors such as M+C Saatchi pitching their services, Palantir staffers attempted to suppress critical coverage by ejecting the author and two other journalists from the event’s main exhibition hall. Palantir further threatened to call the police on a reporter from WIRED.

As noted in the New York Times journalist Mark Mazzetti’s 2014 book, The Way of the Knife, JSOC was leveraging open-source information from LexisNexis as far back as 1986. It does not take much work to imagine how this data affinity could have evolved into the era of automated social media surveillance from companies such as ShadowDragon, chatroom infiltration companies such as Flashpoint, mobile-phone location-tracking data brokers such as Babel Street, facial-recognition firms such as Clearview AI, and offensive cyber products such as those from REDLattice.

Rather than treating spyware as an isolated technology sporadically used to commit egregious civil liberties violations against journalists and activists, researchers might focus more attention on how commercial spyware integrates into US special operations and intelligence agency toolkits alongside other commercial surveillance products. The close partnerships and product integrations are openly advertised more often than one might expect.

Heba Y. Amin

Anthony Downey

Shumon Basar, Jaya Klara Brekke, Konstantinos Meichanetzidis