- Essay

Algorithmic Visions: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Warfare

Anthony Downey

Heba Y. Amin explores the history of the British Middle East Command Camouflage Directorate during WWII in Egypt.

Colin Moss, Middle East Camouflage Directorate camoufleur (1943). A view along a roof top painted with camouflage patterns and textures. In the distance is a similarly painted building among several other industrial rooftops. © IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 3026)

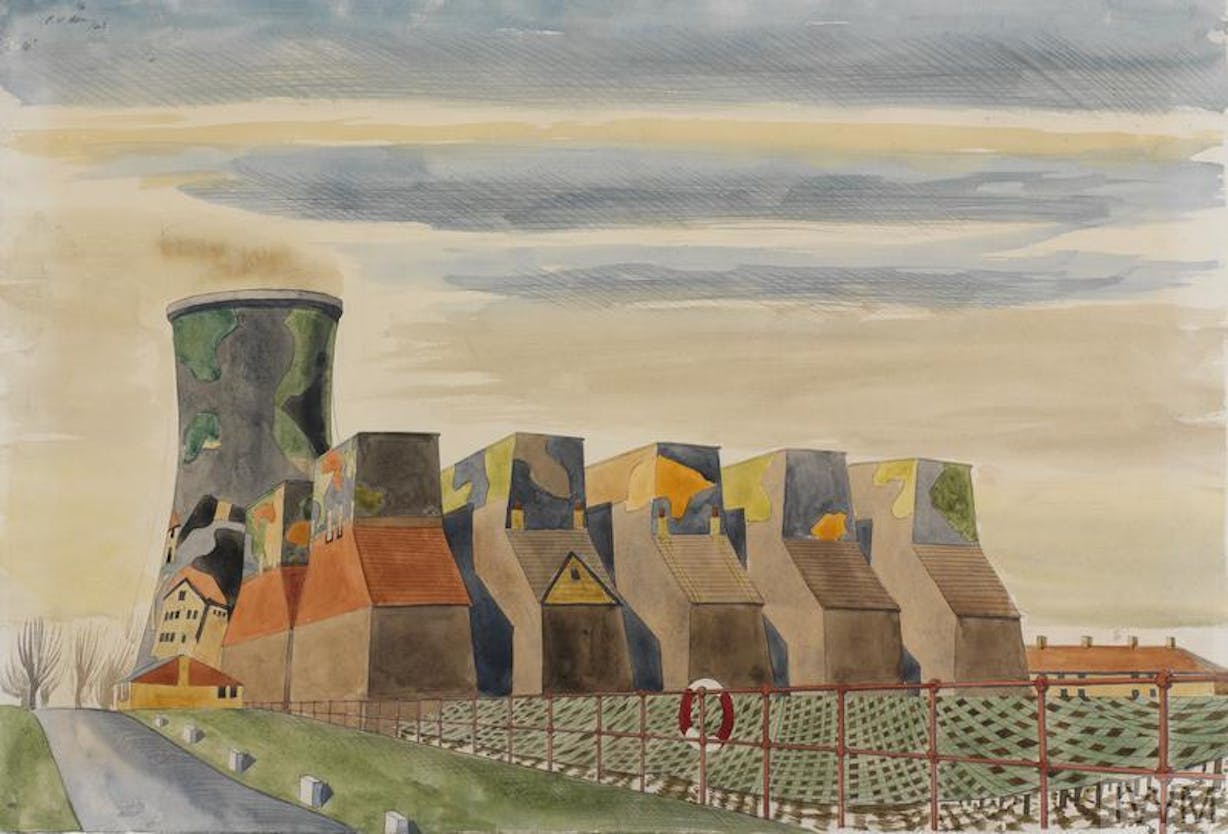

Colin Moss, Middle East Camouflage Directorate camoufleur (1943). A view of a power station with a cooling tower painted in a camouflage pattern. © IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 3024)

In November 1941, at the height of the North African campaign, the British military established the Middle East Command Camouflage Directorate on the outskirts of Cairo. Unlike the camouflage schools that had emerged during the First and Second World Wars, this was the only such institution founded on colonised territory. Its task was to train ‘camoufleurs’ – artists, theatre designers, architects, magicians, and zoologists – in the design of large-scale deceptions intended to mislead enemy reconnaissance. Under the direction of filmmaker Geoffrey Barkas (1896–1979), the unit developed schemes to conceal troops and infrastructure while also fabricating dummy installations to draw enemy fire. This moment in history is often remembered as an instance of creative ingenuity under wartime pressure; yet, when examined further, the Directorate reveals not only the tactical use of art for military ends but also the deep entanglement of camouflage with the colonial scopic regime. In other words, the camoufleurs were instrumentalising artistic vision through a political lens that enforced paradigms of colonial control and domination.

‘Sunshield’ split cover, one half on, one half off a tank in the workshops at Middle East Command Camouflage Development and Training Centre, Helwan, Egypt, 1941. Chiswick Chap / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

Although Egypt had been granted nominal independence in 1922, British military occupation remained entrenched, with Cairo as the logistical hub of British imperial strategy in North Africa. To situate a camouflage training school in Egypt was to transform colonised land into a laboratory of deception, a stage for the exercise of military imagination. Operation Bertram, in particular, was conceived in 1942 to deceive Erwin Rommel and his troops in the months leading up to the second battle of El Alamein. Large sets were built in northern Egypt to mislead aerial reconnaissance – such as the extensive construction of a fake Alexandria harbour – often completed with the help of local Egyptian labourers exploited through colonial compulsion. Barkas’s manual Concealment in the Field (1941) codified the desert of El Alamein into patterns and abstractions that lent themselves to visual manipulation. The landscape was reduced to its surface – catalogued into categories such as ‘plain velvet’, ‘wadi pattern’, ‘polka dot pattern’ – and thus emptied of the histories and lives it contained.1 The Directorate’s illusions depended on the abstraction of land and an ‘imperial visuality’ that ultimately ‘classifies, separates, and renders territory available for appropriation’.2 Transformed into a laboratory for military visual technologies, northern Egypt was reframed as a stage set for imperial war fought between European actors. The desert, for the camoufleurs, was not a lived landscape but an optical problem to be solved.

A Martin Baltimore of No. 21 Squadron SAAF flies over the target area as bombs explode on enemy transport widely dispersed near the Rahman Track, near El Alamein, 1942. © IWM (CM 5905)

A salvo of bombs from Martin Baltimore of No. 21 Squadron SAAF explodes on enemy transport on the road between el Daba and Fuka, Egypt, at the start of the enemy’s withdrawal from the Battle of El Alamein. © IWM (CM 3842)

This theatre of deception was staged explicitly for the eye in the sky. The intention was never to live with the land but to manipulate its image as seen from above.3 Camouflage was not merely a tactic – it was an apparatus of knowledge production. As Barkas himself later wrote, the task of the operation was to design illusions that ‘read correctly’ in aerial photographs taken by enemy planes; the war became legible primarily through its images.4 The aerial gaze was, thus, the decisive vantage point of the North African campaign. Camouflage was part of a broader colonial optic that transformed North Africa into a field of visibility; in particular, the desert of El Alamein was a struggle carried out through and against the image.

Dummy cruiser tanks being constructed by Royal Engineers in a factory near Rouen, 30 March 1940. © IWM (F 3820)

Photograph of the framework of a dummy tank under construction at the Middle East School of Camouflage in the Western Desert, 1942. Photo by Captain Gerald Leet. Chiswick Chap / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

It is not insignificant that artists proved central to the British military’s strategies of deception. Many of them were engaged in the Surrealist movement: their expertise in optics, disorientation, and the manipulation of scale allowed them to reconceptualise the battlefield as an image to be staged for the aerial perspective. Roland Penrose, a central figure of British Surrealism, had already been advocating camouflage as a form of artistic research even before the war began. He gave lectures on camouflage to the Home Guard, using painted props and photographic slides as well as drawing from art history and Surrealist experiments in perception, to demonstrate how techniques of optical deception could be harnessed for military purposes.5 This was not a marginal contribution but an integral tactic: the Surrealist imagination was weaponised, transforming avant-garde experiments in estrangement into operational tools of empire. Yet the camoufleurs’ work also reveals how artistic practice itself generates knowledge; through acts of making and testing, they developed methodologies that exposed the mechanics of seeing during war.

The aerial photograph, the reconnaissance film, and the deceptive dummy installation were all instances of what filmmaker Harun Farocki referred to as ‘operational images’: images that are not intended for human spectatorship but, being part of a process, are designed to direct operations.6 What was staged in the desert in El Alamein prefigured today’s operational scopic regimes – where images do not merely represent but also act as weapons. The camoufleurs, in this case, were already producing images that acted: the dummy tanks were constructed so they would register as ‘real’ in reconnaissance photos, while the camouflaged pipelines were designed to misdirect enemy intelligence.7

Troops carrying a dummy Stuart tank, 3 April 1942. Photo: George Groom. © IWM (E 10147)

Western Desert, Egypt, 22 August: The Germans wasted a lot of ammunition on this dummy tank, set up for just that purpose, near El Alamein. Public domain.

The Directorate designed objects to be viewed from above – for the German Luftwaffe camera – rather than below. The camoufleurs contributed to a transformation in visuality whereby the image-referent no longer needed to be convincing to the human eye at ground level: these were not images to be admired, but images to deceive the gaze from above. In his theory of non-ocular sight, Farocki states that owing to the increasingly machinic, ‘operational’ production of images, the photograph did not even need to deceive the aerial photographer; rather, it needed to deceive the machinic gaze. This recalibration of perception – from embodied to machinic vision – paved the way for contemporary regimes of drone vision, satellite imaging, and algorithmic targeting.

The aerial vision first exercised in North Africa was steeped in Orientalist tropes and a mode of perception that exposes the so-called Orient as governable and subordinate. Western epistemologies have long called for transparency that deem all subjects visible, knowable, and legible. This motivation is bound to colonial domination; how ‘to know’ the other was always a means to classify and control. Indeed, colonial photography established a precedent for contemporary visual technologies that continue to demand legibility from racialised and gendered subjects.8

Contemporary data extraction – not unlike colonial data gathering – appropriates human life and encodes racialised and Orientalist biases into algorithms and databases. Digital Orientalism, as it has come to be called, emerges from the colonial scopic regime, extending its logic from the photographic archive to the digital cloud, from the reconnaissance image to the drone feed. Under colonial rule, landscapes in the Middle East and Africa have historically been used and continue to be utilised as laboratories for nuclear testing, drone warfare, and surveillance technologies.9

This is not incidental: the logics rehearsed in Egypt that once transformed the desert into an optical stage for deception now sustain the testing grounds of algorithmic warfare for colonial and neocolonial powers. Gaza and the West Bank, Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, and the Sahel have been repeatedly instrumentalised as experimental terrains where new techniques of sensing, targeting, and automated killing are trialled before they are deployed and capitalised on elsewhere.10 The question that arises here is how marginalised and targeted populations can evade the ubiquitous gaze of the machine for their own survival, and also intervene in the algorithmic logic of AI to take back control of their own image.

All of this leads me to ask: if camouflage under empire exemplified a scopic regime of domination, can camouflage be reimagined otherwise? Camouflage, as a warfare strategy, was never a disruption of colonial vision but rather an extension of it. The illusions engineered by the Middle East Command Camouflage Directorate worked because they engaged the aerial gaze; camouflage, in this case, was a form of image-making that crystallised the violence of colonial vision and imperial control, which is rooted in the dispossession of the land and its people. Instead, how can camouflage be used as a methodology to undo the political mechanisms embedded in contemporary representation?

What would it look like to reverse the logic of image politics of the last 200 years? This question is particularly urgent in the current political climate, where marginalised populations are hyper-visible to militarised technologies such as drones, biometric recognition, satellite monitoring, and predictive artificial intelligence, but they are invisible to the protections of law.11 Édouard Glissant’s call for a ‘right to opacity’ offers a provisional starting point to think about camouflage outside of its colonial, military history.12 If we consider Glissant’s key points in his Poetics of Relation (1997), opacity is understood as a model of resistance to Western modernity’s imperative that everything should be explainable, if not transparent (to the ethnographic impulse of the colonial scopic regime, for example). Opacity as a form of resisting appropriation becomes an affirmation of the right to remain unassimilated, or consumed, through and by the colonial gaze.

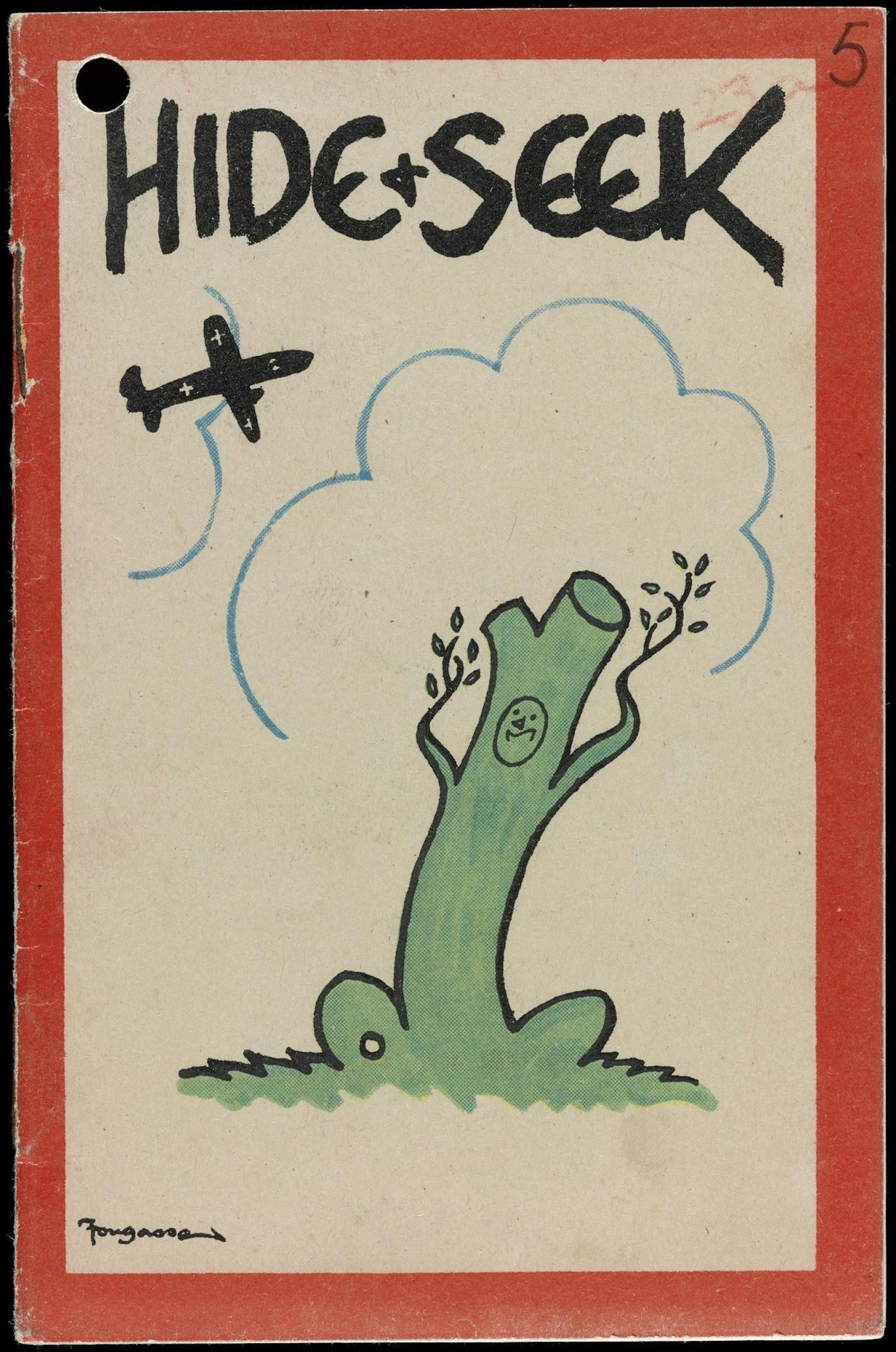

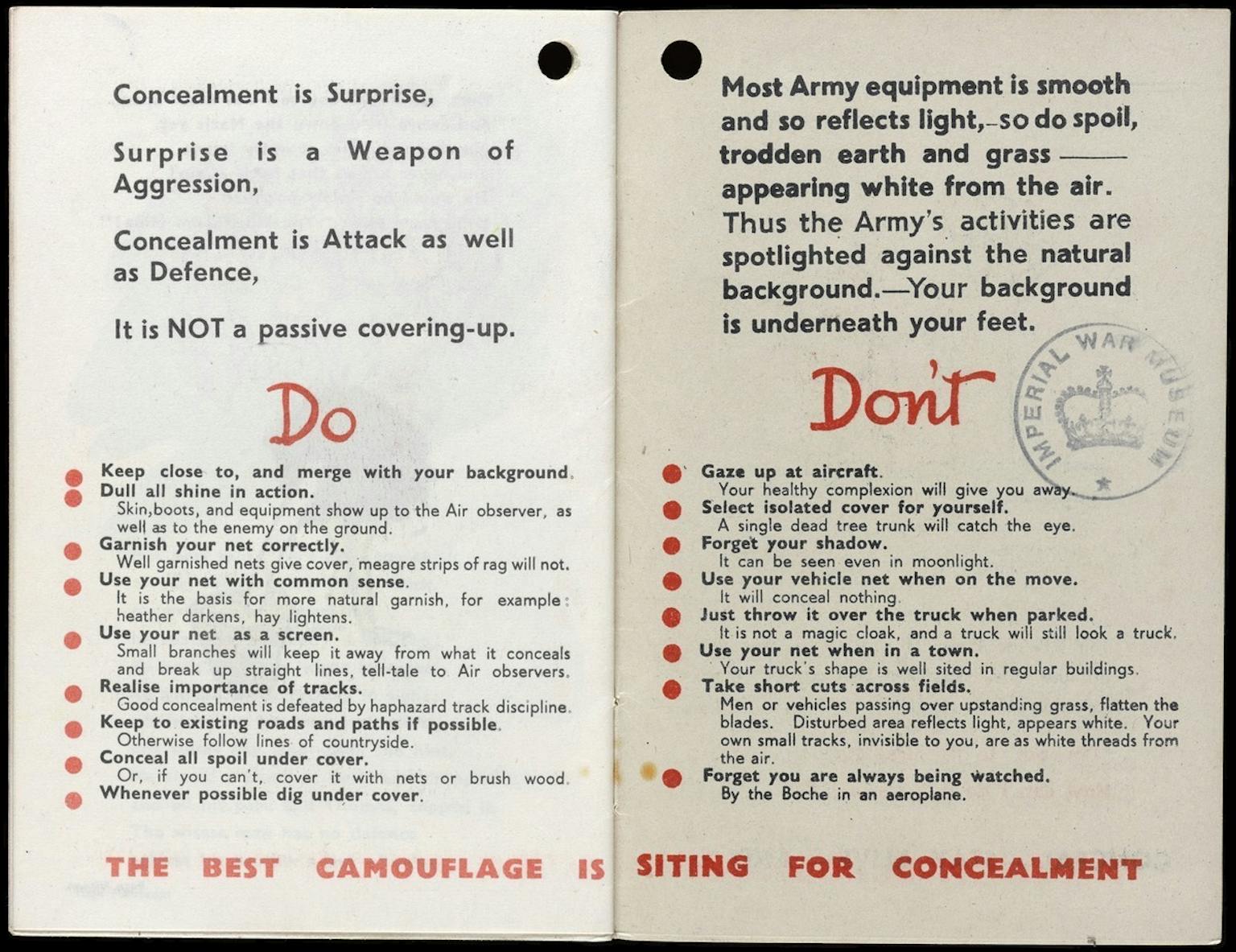

Hide and Seek: A Story of Concealment, Camouflage Development and Training Centre. Date unknown. © IWM (LBY [O] 90 / 2334-1)

Hide and Seek: A Story of Concealment, Camouflage Development and Training Centre. Date unknown. © IWM (LBY [O] 90 / 2334-1)

What I want to contemplate here is what counts as a legitimate view: who gets to look, and under what terms? To be opaque, in this case, is not to disappear; it is to insist on being encountered without reduction, to refuse capture (assimilation) by the observer. To undo the logic of image-making is to live in ways that cannot be fully translated into the categories of empire or algorithm.

For the camoufleurs, artistic experimentation became a methodology for domination that was subordinate to the colonial gaze. To revisit those methods today means one must acknowledge their alignment with military objectives and how artistic practice was instrumentalised to maintain structures of violence. To reclaim camouflage, then, is to reverse the theatre of deception inaugurated in North Africa.

Whereas the Camouflage Directorate transformed the desert into spectacle for imperial optics, counter-camouflage reclaims concealment as a mode of resistance to being seen. To conduct research through images, where practice enacts a critical methodology, can offer a way to engage the condition of optical resistance – not by rejecting images but by intervening in their logic of visibility.

Anthony Downey

Stephanie Bailey, Radha D’Souza, Adam Broomberg, Françoise Vergès, Anjalika Sagar, Nour Yakoub, Gaurav Sinha

Alia Al Ghussain and Matt Mahmoudi, hosted by Jaya Klara Brekke