- Writing Gaza

Writing Gaza

Omar Berrada & Shivangi Mariam Raj

Translated from Arabic by Omar Berrada

What does survival mean in the context of this genocide?

Have all the dead survived? Are all the survivors weeping?

As an artist and a father, I live in Gaza amid a genocide that has affected not only people but history itself, destroying the city’s centuries-old features, resulting in famine and a siege that has lasted more than 700 days.

I, the artist Marwan Nassar, am addressing every free person in this world. These words are not for those who have let us down, who have sold their conscience. They are for compassionate hearts. They are for the free alone.

The pain we experienced was not merely a passing emergency, but an earthquake that reshaped our social and political structures from the roots up and altered the parameters of our daily lives, individually and collectively. Amid this devastation, I felt that all means of expression had fallen. Writing, literature, visual arts – all seemed powerless in the face of the horror. There is a huge gap between what is actually happening and what we can represent or express. Still, we try and seize a moment of survival through cultural and artistic action, for the new reality we live in requires different visual and verbal tools.

The artistic and literary orientations that emerged during this genocide may form a basis for future studies and research. They shed light on the profound psychological impact experienced by every artist and writer who attempted to express themselves amid famine and deprivation. In our context, art is not a luxury, nor is literature a way of beautifying life; they are acts of defiance, resistance, and confrontation with the siege, by way of beauty and meaning.

Anyone who contemplates the artistic field will know that, in periods of struggle, it cannot be separated from politics. My experience falls within this intersection. Through art, I tried to restore what was destroyed in the visual and oral landscape, to build a foundation that would strengthen Palestinian steadfastness and social cohesion.

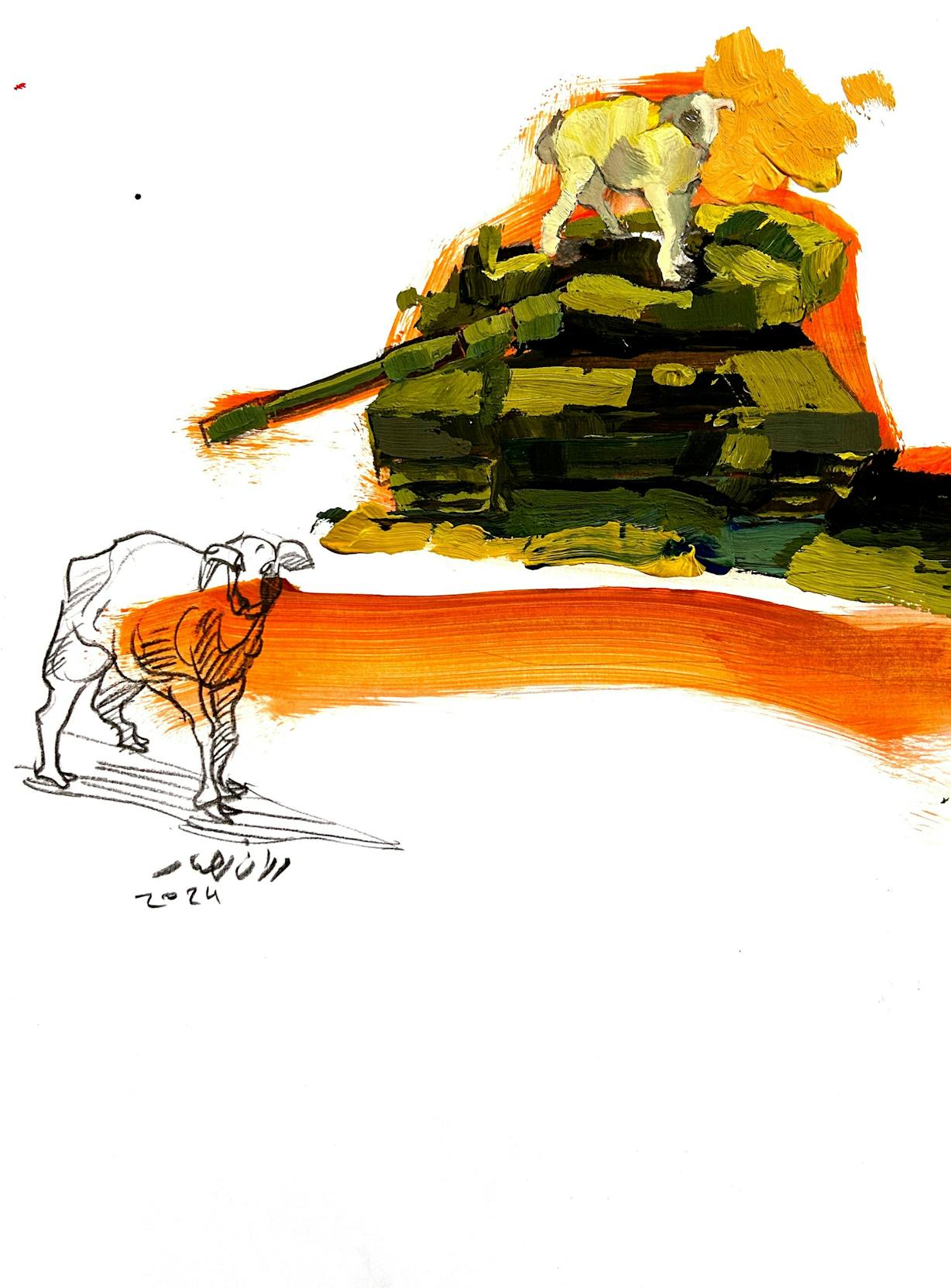

Marwan Nassar, Untitled (2025). Courtesy of the artist.

Marwan Nassar, Scenes from Daily Life (2024). Courtesy of the artist.

In light of this reality, my artistic priorities have changed; formal experiments and experimental research are no longer ends in themselves. I found myself turning to retelling what I have seen and lived through, delving into the details of the pain that surrounds me. I began following the news and contemplating media images, not out of curiosity, but to feel that pain and rearticulate it visually, in order for my work to carry a human message that might touch the depths of those who see it.

The genocide has made daily living almost impossible, due to limited options and scarce resources. Over time, the war has taken on many forms. I have come to refer to these transformations as an ‘architecture of death’, for they have not been limited to the human realm but have also played a systematic part in the destruction of cultural infrastructure and attempts to erase the visual identity of the city.

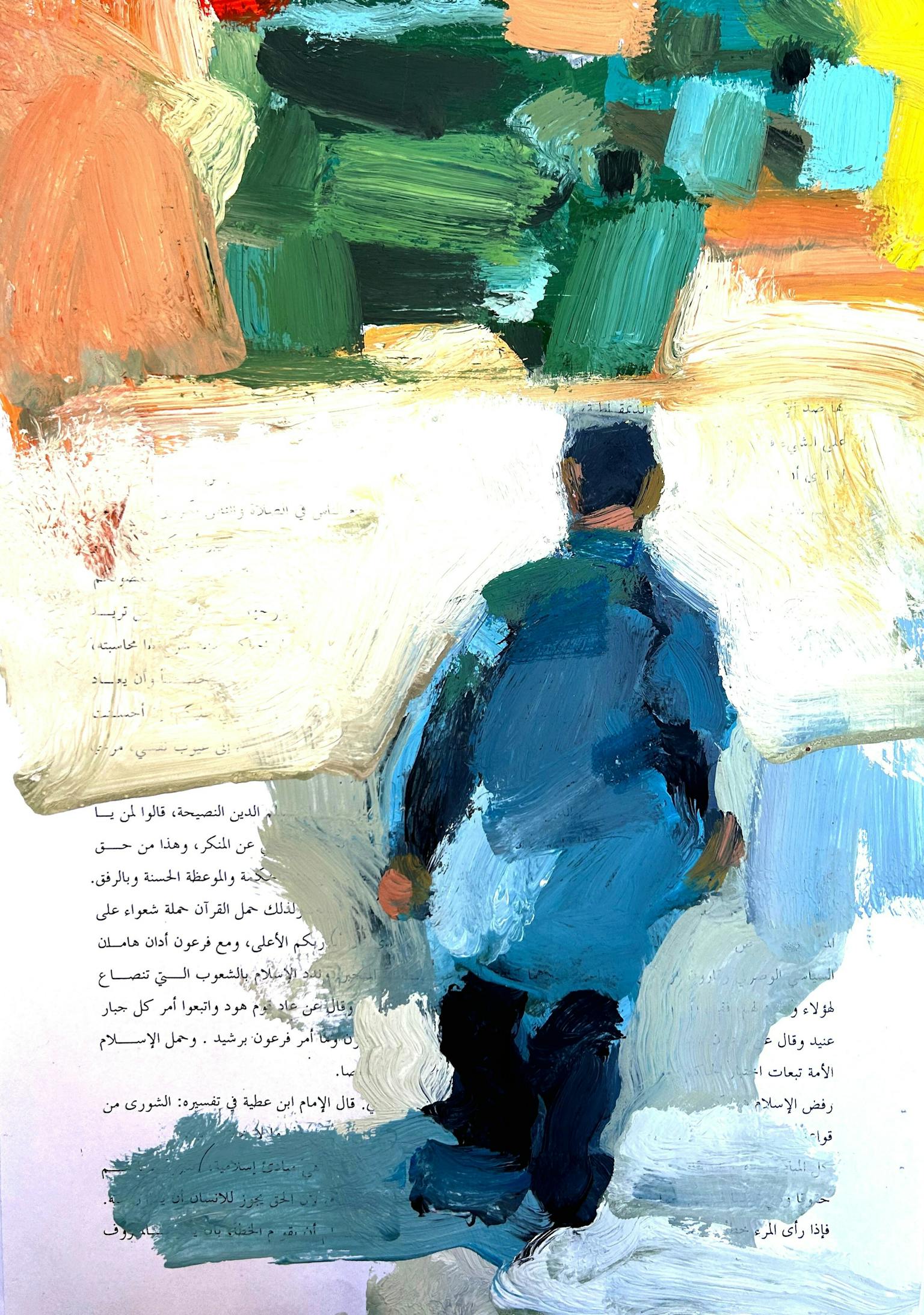

In this context, I found myself forced to rely on available materials, in line with the day-to-day nature of my documentary efforts. This led me to use pieces of paper with texts or words written on them, which became part of the painting. This was not only out of necessity due to the lack of materials but also took on a symbolic dimension in relation to the obliteration of the nation’s identity. I considered each word printed on these sheets to be a narrative, representing an element of Gaza's history, as if I were loading each letter with the weight of our memories and culture.

Marwan Nassar, Scenes from Daily Life (2024). Courtesy of the artist.

My work on these surfaces involved a dual action: erasure and emergence. When, over the texts, I place layers of colour laden with contrasting emotions, I am like someone summoning the hidden presence of a place, even as it is being erased. This visual strategy went hand in hand with my developing a personal philosophy of working with Arabic letters and with the idea of disappearing landmarks. I used any available pieces of paper, research notes, and old archival materials and made them a part of a new visual grammar. I tried to combine drawing, text, and colour in a tense but truthful harmony. If not for the harsh circumstances and the shortage of materials, this experience might not have succeeded in this way.

The genocide made me scan the small corners of existence, searching for forms of life, looking for a smile here or a glimmer of hope there that might hold a ray of light at the end of this long tunnel. In the midst of this process, I turned over many difficult scenes and words, trying to find new meanings for them, or synonyms I could use to forge a visual sentence that might express the condition of clinging to hope.

Marwan Nassar, Scenes from Daily Life (2024). Courtesy of the artist.

I wandered a lot, whether in the markets, among the tents of the displaced, or on the beach, in a personal attempt to recover from pain. There, in front of the sea, I found a vibrant life, a latent energy in people’s adherence to their daily routine, as if the sea itself were an embodiment of resistance. The people of Gaza have always had a deep connection to the sea, despite the death and the cannons that lay in its depths. But through their persistent presence and the practice of rituals they cultivated before the war, it seemed as if they were saying: this sea is ours, this sky is ours, you are the strangers, your presence is provisional.

I read these signs in the eyes of the fishermen and the displaced people who made the sea their safe haven, however temporary. Just as I documented scenes of death, I also painted scenes of life. I painted the boats not only as a symbol of survival, but as a living antithesis to the word ‘death’. I wanted to imbue the sea with symbols of life and of attachment to life in the face of loss and destruction.

There is a scene I will never forget: a man in his seventies in front of his tent, building a house of sand on the beach, as if trying to restore his memory with his own hands, gathering the scattered pieces of his soul after being displaced from his home under threat of death. The sea was the last possible place for him, the only available roof against the sky.

Looking at the body of work I produced during this period, one notices a fundamental difference with my previous output. My brushstrokes took on a thickness laden with feeling, my colour choices broke free from academic calculations, becoming bolder, more chaotic, and more passionate. I no longer sought familiar compositions, but rather the act of painting itself, as an immediate response to news, shock, or tragedy, as if the work were born in a rush, before the emotions had cooled down.

My experience constantly fluctuated with my general mood, navigating between quick drawing experiments. I started drawing with charcoal pencils and completed dozens of sketches that looked like maps of a burdened memory. Over time, the images crystallised within me; I had reached a new state of artistic maturity and a deeper understanding of my own trajectory.

In his reading of my work, writer and poet Mahmoud Abu Hashhash describes this trajectory as follows:

Between ‘Gaza beach’, completed before the war, with its clean, calculated brushstrokes suggesting a serenity only deepened by the sea’s spectrum of blues acting as a backdrop for two people standing before a red boat, and his later paintings (one of fishermen in the middle of a stormy sea, a series of colourful portraits, and his recent painting of martyrs who died by burning), a journey of transformations unfolds, one that did not begin with the war, but which the war accelerated and intensified. The genocide forced his artistic practice into a test of survival against the crushing weight of threatened, fragile, and absurd existence, compelling a search for meaning and for the essence of experience, as a way for art to avoid falling into futility.1

Marwan Nassar, Gaza Beach (painted before 2023). Courtesy of the artist.

Marwan Nassar, Scenes from Daily Life (2024). Courtesy of the artist.

Throughout history, art has been considered a human movement to express people’s hopes and aspirations. Before the genocide, I wrote a text in which I attempted to link the global political context with the humanitarian situation in Gaza, under the title: ‘Picasso’s Guernica and Gaza’s Guernica’. In it, I wrote:

When Picasso painted Guernica, he did so at a time when killing was causing severe trauma to the human environment. This painting produced new axes and turning points through which ideas of liberation emerged to speak for humanity in general; it became a representation of injustice and a call for liberation from the chains of intellectual and political hegemony. But Gaza continues to experience a new Guernica every day, and to produce new forms that recall Picasso’s method. Will such excess of killing shock the world and awaken the conscience of humanity toward supporting our just causes and legitimate demands for liberation and independence?2

If I was to imagine a painting after the war, it would not be there only to testify or only to present an embodiment of survival, but to create a visual document that attempts to amplify global human solidarity and present the war narrative from the perspective of those who survived and bore witness. The war has imposed an immoral context on us, reducing human beings to numbers in media reports. Hence the symbolism of human presence in my work, which conveys a profound challenge in the face of pain, even as it embodies the sense of betrayal that has settled deep within the human soul.

As an artist, I am fully aware of this deliberate political approach and of the attempts to tame the viewer’s feelings towards us, to reduce our existence to mere news or passing numbers. Therefore, I have strived to construct visual concepts that resist such vulgarity, that aim to portray Palestinian human beings as rooted extensions of the land, whose shadow never leaves the duality of life and death, but remains present in every scene and every movement, like a spirit carrying its wishes along and embodying both catastrophe and steadfastness at the same time.

I examined people in detail, their faces and gestures, with a view to conveying them through colour, to dignifying human expression through the means of art. During this period, I completed hundreds of artworks and sketches on paper, including a series entitled Not Faces but Feelings.

In this series, I tried to get closer to the state of worry that weighs on people, and the restless anxiety that affects their behaviour and their interactions with their social environment. We have all grown old inside: our features no longer represent us or bear our distinctive attributes; they express our exhausted, war-torn inner selves.

The title To Survive to Witness, which was suggested by Mahmoud Abu Hashhash, truly encapsulates my second solo exhibition of this war, held on the Art Zone Palestine platform. The show included nearly 300 artworks produced during the genocide, as well as works completed before the war as part of a project entitled Stories of Places. It provided a space to interpret my work in light of the visual and artistic transformations that have marked my career. Survival here was not merely physical. It is the survival of consciousness, of the ability to see and to bear witness to what happened.

Throughout its history, Palestinian artistic practice has been faithful to its surrounding reality. It has evolved alongside political changes without reducing itself to narrow ideology. On the contrary, it has opened up to contemporary aesthetics. I am part of this current, having taken the path of combining everyday visual narrative with aesthetic freedom, which has allowed my work to oscillate between political and aesthetic modes, renewing itself, remaining alive and capable of interacting equally with all interested viewers and those who are in solidarity with us.

Mahmoud Darwish said that the things we lost can never be replaced. From this perspective, I see the practice I developed in the shadow of genocide as, first and foremost, a human commitment stemming from a desire to put things in order and reinvent the forms of everyday life in an attempt to stimulate solidarity around what is happening. Secondly, for me, it was an internal demand, like a path to survival. Painting in the midst of havoc and ruination is one of the great challenges that have profoundly affected my work, both in terms of choosing my subjects and adopting a mode of expression filled with a deep desire to cling to life amid the turmoil of daily events.

Marwan Nassar, Untitled (2025). Courtesy of the artist.

My artistic practice has changed a lot from what it was before the genocide, as though the war had taken me to more insightful and honest places and made me reflect on the truthfulness and usefulness of expression in the midst of death. Therefore, I no longer see my works as mere paintings but as material laden with uncertainty. Are they finished works of art that can form the basis of a stylistic orientation? Or are they just transient responses to an event’s brutality and how close or far it is from me personally?

Ultimately, my daily drawing practice has had a double effect: on the one hand, it is a means of documenting the moment and interacting with my surroundings; on the other hand, it is a practice burdened by responsibility, since I feel I am acting as a witness to the reality of war. And yet I cannot deny that this practice – the pursuit of truthful expression – offers a kind of artistic fulfillment, especially when drawing becomes an act of resistance and a space to search for meaning in this nihilistic world.

Omar Berrada & Shivangi Mariam Raj

Hanan Habashi

Elisa Adami