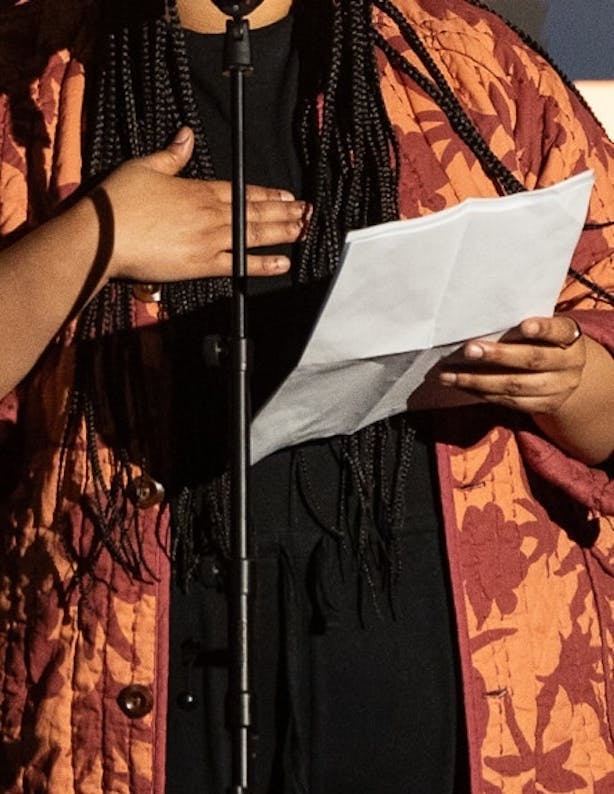

- Poetry

In the Name of Love: For Bano Bibi and Ehsan Ullah

Warsan Shire

Fatimah Asghar reflects on the gender-based violence of a patriarchal culture in which the autonomy of women is seen as a threat to family ‘honour’.

my wounded country, there is no love

– Saint Levant

I’ve always been fascinated by the last words of people who have died. One of the stories that struck me growing up was the story of Bhagat Singh, a revolutionary leader who fought against the British in colonial India. It was reported he went to his execution reciting poetry. In one of his works, he wrote, ‘They can kill me, but they can’t kill my ideas. They can crush my body, but they will not be able to crush my spirit.’1

Ideas are dangerous to those in power. It’s why, when a genocide is being committed, people go for the poets, the intellectuals, the schools first. It’s why memory, history, art, and writing are so important. Because when you see something, when you see someone articulate a truth so clearly that it awakens something in your own heart, you can’t un-remember it. It becomes part of you; it changes you.

On 4 June 4 2025, Bano Satakzai was murdered alongside her husband, Ehsanullah Samalani. The two had been newly married against the wishes of their family. Accused of having ‘an affair,’ Bano’s family took the issue to Sardar Sherbaz Khan, a tribal leader. Sardar issued that the relationship was ‘immoral’ and ordered them killed. A group of armed men brought Bano and her husband to a remote area, before executing them, in what is considered an honour killing.

Even approaching death, Bano Bibi articulated her terms. She asked to take seven steps forward. She dictated her terms. She walked her seven steps. She said, ‘You can shoot me. But nothing more than that.’

My wounded country, blistered full of death.

In my wounded country, a young woman falls in love. In my wounded country, love like this is not allowed. In my wounded country, a young woman falls in love anyway. In my wounded country, a young man falls in love. In my wounded country, they chose each other. In my wounded country, they’re both murdered. In my wounded country, onlookers watch and record on their phones. In my wounded country, no one helps them. In my wounded country, no one lifts a finger.

Honour: what is it? A heavy word, a beautiful word. Every morning, I pray to be in alignment with myself, I pray to honour myself and what I am. Honour lights my day, shows me a path forward. But my honour is on my own terms – I’ve carved out my life for it to be this way. Honour is specific; it comes from our pursuit of our truth. Our truth of knowing who we love, why we love, what we love for, and how we go about getting our love.

Love: what is it? bell hooks writes, ‘Love is as love does.’ Love is an action, not a feeling. Love is an action in the self: how willing you are to undo the knots of violence inside you so that you can see someone else clearly, so that you can treat them in a way that nourishes them, rather than detracts. Love, when reduced to control, becomes violence. Love, when tied to a warped sense of honour, becomes a disease.

In the lands I come from, at least one woman is killed a day in the name of someone else’s honour. Usually a man’s. Usually a man who wants to control how a woman is behaving, who views this woman’s body as an extension of his own and therefore doesn’t consider the gravity of what it means to murder someone. In these cases, the murder is justified by those who carry it out. The death is seen as legitimate because it was done to cleanse a bloodline of men of their shame; their embarrassment propelled by a daughter who chose to have a life of her own, a life where she loved how she chose to love.

Bano Bibi, who chose to love among a world of men who would not let her. Bano Bibi, who asked to walk seven steps, who moved at her own pace. Bano Bibi, among a group of onlookers, phones recording her last moments.

There she is: Bano Bibi with her lover, blood on the ground, life leaving their eyes. There they are: the stars in the sky, the pinpricks of what could have been if they were allowed to love differently, if they were allowed to be who they could be, if they lived instead of being cut down. Above us, they live, eternal. Above us, the night, its openness, dares us to love beyond what we think we could, beyond someone else’s honour, beyond fear.

All my life, I have collected small stories of wild women, queers, deities, high priestesses, spirits, and jinn who have decided to live life on their own terms. Who, in their living, light a torch for us to light a path in ourselves. Throughout my life, I’ve collected stories of sacred rage – the fire that forms against injustice, the fire that moves us to imagine a better future.

One story that I love is the story of Pacha Karmaq, the Father of the World in the Peruvian Ichma culture, which pre-dates the Incas. While creating the first man and woman, Pacha Karmaq forgot to provide food for them and the first man died of hunger. When her partner died, the first woman raged against her father, cursing him for his neglect. In praise of her sacred rage, he made her fertile: he created a body that could bring another into life. Here, rage was not shunned: it was rewarded. Here, even gods can make mistakes, even gods need us to tell them where they erred and how the world could be better. Here, we’re asked to speak what we need, to demand what we need, to fight for it – not only for ourselves, but for those who come beside us, for those who come after us, for the world that we wish to see.

Throughout my life, I’ve seen many things resembling apocalypses. We live in a world where entire villages are being flattened by bombs, and all of it is broadcast to our phones. We live in a world where multiple genocides are raging – where people in Sudan and Palestine are being systematically starved by oppressive forces and governments are blocking basic humanitarian aid.

We’ve seen disease still our movements, bring us inside as members of our communities have died around us. We’ve seen police brutality, anti-Black violence, Islamophobia, transphobia, and fascism rise in ways that rival dystopian novels, while people still hustle to try and get to work and provide housing and shelter amid impossible economies.

The truth is we’re dying – all of us, all the time. The truth is we must insist on living – all of us, all the time. The apocalypses are here: they are many, they are pressing, they are urgent. We must find our sacred rage: the things that we are willing to live for, the things that we are willing to die for.

We must hold our heads high like Bano Bibi, even when the gun is pointed at us, and demand for our lives to be on our terms, demand what we will no longer tolerate.

For weeks, no one did anything. The videos went viral online, spreading like cursed wildfire. Two murders, in plain sight, recorded from multiple angles. And the police and government and officials all sat by, waiting for it to pass.

When they finally did something, 15 people were arrested, including Bano Bibi’s mother, who stated that the deaths had to happen to preserve the family’s honour. How far have we come from ourselves, where perceived honour is seen as more valuable than a life? Where many people are forced into arranged marriages in the first place, their lives at the whim of everyone else’s decisions rather than their own?

I wonder – what was Bano’s life like when even her own mother and brother advocated for her murder. Where did she learn love? How many deaths had she survived before this moment, before she was shot down in the sand? What gave her the courage to love someone so much that to die beside them was better than to live?

bell hooks writes: ‘The first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead, patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves.’2

A concept that I have heard often, but has been hard for me to conceptually understand, is that patriarchy hurts everyone, including men.

As someone who is nonbinary, someone who is femme, it seemed impossible to me that the people who directly benefit from a system could be hurt by it. But the closer I got to my male friends, the deeper I could see some of their pain – the way they had been conditioned out of such basic emotions, the way that they had been taught to see incredibly normal things (such as crying when you are in emotional or physical pain) – as weakness. I watch these men, people I love, become more and more dissociated from their feelings, spiralling into a whirlwind of behaviour that they themselves don’t even understand. I watch them struggle to slow down, to touch the soft places inside of them, to even begin to be able to understand what they are feeling.

My wounded country, a war machine.

In the land I live in now, there are mass shootings all the time; our proclaimed leaders send weapons to flatten cities full of children and label them ‘insurgents’. The land I live in now can’t look to its past, prefers to pave it with manicured gardens and fences, to build mansions on top of gravesites. The land I live in now tries to start its history from the creation of the nation-state, and anyone who dares to remember beyond – or outside – of that has a target put in their back.

The lands I come from do the same, the scars of colonisation, war, terrible leaders large and looming, the government so delusional they think they own the land below them, the sky above, the mountains that have existed for thousands of years, jutting out of the ground.

The land I live in now, clinging to lies of blood and steel. The land I come from, clinging to lies of honour and nation. The land I come from, writing and rewriting itself, forgetting what came before. The land I live in now, boasting its flag and its colonisation, bombs sent out across the world.

I’ve always hesitated writing about honour killings because of where I live now, because of how the stories of honour killings in the Muslim world are warped and used as ammunition for Islamophobia. In the West, people have often come up to me when they find out my family is from Pakistan, talking about the unsafety, the honour killings – all coded to mean that my people are backwards, somehow inferior, barbaric. Is it not barbaric to live in a country where school shootings happen at such a rate that they don’t even make headline news anymore? Where children are taught lockdown drills in case someone comes in their place of learning with a gun?

Is it not barbaric to live in a country where they send bombs that indiscriminately kill children across the world? Is it not barbaric to live in a country where police systematically shoot Black and Indigenous people with no repercussions?

What violence is considered backwards and what violence is excused often depends on the ones holding power. And not writing about honour killings for fear of avoiding racist remarks isn’t helping anyone either. We can’t exist in a world where we need to appease our oppressors with the right narratives – the only thing that we can do is be honest and true to what we are witnessing, to say when something is unjust.

Courage, is what we all require. Courage, like Bano Bibi, who asked to take her seven steps knowing she was going to be executed; courage, like Bano Bibi, who decided to love even when people told her that she couldn’t, when she was threatened.

Is there a place that exists where we can be safe? Where love can bloom into more love?

In my heart, I know that safety is an illusion. It’s not guaranteed to anyone, even when we painstakingly try to cultivate safety it crumbles around us all the time. As Octavia E. Butler said, “All that you touch, you change. All that you change changes you. The only lasting truth is change. God is change.’3

Bano Bibi touched this world. She touched the ground, each of her last seven steps. She touched the world, she was touched by the world, and then she changed. And, Inshallah, her story will continue to change us in all the ways that it can, it will continue to ripple through us long after her body is gone.

Seven has deep spiritual weight across many cultures – in some of the Abrahamic traditions, it’s believed that God created the world in six days and rested on the seventh. Seven represents the creation of a life cycle, a moment of spiritual ascension. In Buddhism, seven guides the seven factors of spiritual enlightenment. It is said that when the Buddha was first born, he turned towards the north and walked seven steps, each met with a shower of rain. In Hindu weddings, the number seven seals the sacred vows. And in many Indigenous traditions on Turtle Island, there are the seven sacred directions. Seven holds a meaning: it’s a portal into something that is beyond the material world in which we are so often stuck.

We will never fully know what the significance of those seven steps was for Bano Bibi. Why she asked for seven, what they meant for her. But we do know that she asked for seven, that she walked seven, that when she was ready, she gave permission.

Warsan Shire