- Mission Statement

7. Measuring Relevance and Success

Radha D’Souza, Rasha Salti, Anne Barlow

Mission Statement 00: Why Now?

This is a lightly edited transcript of the sixth session of Ibraaz Mission Gathering 00: Why Now? which took place on 21–22 February 2025.

Panellists: farid rakun (ruangrupa), Ibrahim Mahama, Jaya Klara Brekke

Moderator: Stephanie Bailey

Respondents: Al Hassan Elwan, Muhannad Hariri, Declan Colquitt, Oscar Guardiola-Rivera

Stephanie Bailey: This roundtable will explore questions around structure, organisation, and governance in terms of developing institutional or collective initiatives. I am particularly excited for this session, more so now after yesterday’s discussions around words like community, network, and public.

As a copyeditor, discussing words and what we do with them is one of my favourite things; and as a copyeditor, I can tell you there is no single right answer. Especially when it comes to discussing words within the context of a house style of a publication, which sets the grammatical rules. For example, to follow US spelling and punctuation, to capitalise proper nouns, or more specifically for the arts, to capitalise specific art movements?

In copyediting, there is truly one golden rule: pick a convention and stick with it. Until it’s time to change it – because common conventions do shift. The word ‘internet’ is a really good example. When working on the house style for the publication You Are Here: Art After the Internet (2014), edited by Omar Kholeif with contributors including Sophia Al-Maria, Erika Balsom, Jesse Darling, and Ed Halter, among others, one of the major issues when deciding on the book’s house style was whether to write the core subject of the book – the internet – in lowercase or uppercase. At the time, and I truly cannot believe this when I think about it now, ‘Internet’ was capitalised: edited to uppercase according to the APA and Chicago style guides, and by Frieze and Artforum, as examples. Yet by that time, the internet was becoming as common as the telephone. After reaching out to contributors of the book, we went with lowercase.

The reason we spent so much time thinking about capitalising internet or not, was because of the term in question: ‘post-internet art’, a category used to define a particular scene in the early 2000s, whose capitalisation across publications was anarchic to say the least – and those who were considered part of it had an equally anarchic relationship to being historicised. On one end of the spectrum, Frieze went with full caps and a hyphen, ‘Post-Internet’, suggesting a historical art movement; while Rhizome chose to treat ‘postinternet’ as you would postmodern, in the lowercase and as one word, suggesting a condition, an aesthetic, rather than a historic point in time. For our publication, we went for lowercase, but with a hyphen, given the concept was art after the internet; though in hindsight I would have gone with Rhizome or kept ‘internet’ capitalised – but at the time, the shift was in motion.

Now, these might sound like pedantic, trivial matters, but in the context of written, and indeed printed or even more importantly official or public text, words and how they are treated are imperceptibly important. One decision can ripple like a wave until it becomes convention: either eternally capitalised and thus exceptionalised, like a name, or lowercased to signify its commonality. So, for example, when we were editing Ibraaz we chose to not use ‘the West’ and to not uppercase it when it appeared, and we would refer to it as ‘the western world’.

That’s what I love about the anarchy of house styles across publications; they reveal how words are fundamentally unstable, because they can mean different things to different people; they are a commons whose meaning is held up by a kind of dissonant consensus. And with that in mind, I wanted to zoom in on the keywords in question today: institution, structure, form. Because while we have one word to describe the thing, ‘institution’, there are, in fact, many different types and morphologies of what an institution actually is. An art institution is one of them, and within that you have types: a gallery, a museum, a kunsthalle, and so on; which is to say, when we say we are thinking about what it means to become an institution, we are saying we are thinking about the form this particular institution can take.

Now, I’ll put my copyeditor hat back on one more time. When we talk about institutions in the noun form, we talk about the thing. That’s the ‘-tion’ part of the word: a suffix added to the end of a verb, which describes an action, and less commonly to the end of an adjective, a describing word – so ‘contrite’ becomes ‘contrition’ and ‘describe’ becomes ‘description’. It’s the same with institute and to institute. An institution is the product of the act of instituting: to introduce, establish, and set in motion a structure produced out of action, or a series of actions; to act. And what we are privileging in this collective thought experiment, and what I know our panellists are engaging with, is the action part, which is where the synonym for institution comes in: organisation, to organise.

With that, I will recall the key questions for this panel: How to organise an institution? How to structure an organisation in a sustainable and fair way? How to structure a core team that facilitates the networking of networks, both offline and online, in order to create a truly generative platform for knowledge building and exchange? My brief to panellists was to explore how they conceive or engage with institutional or organisational structure as a holding pattern intersecting economies of contextual, material scale and means; a system that enables ways of working that reflect and respond to the influences that have shaped it. To introduce their responses, I will read out the specific prompt I sent to each speaker.

farid, you have mentioned wanting to discuss ruangrupa’s ‘Jakarta-based practice as samples of worthy and liberating failures’. It would be great to connect this to how ruangrupa experimented with lumbung on an unprecedented transnational scale through documenta fifteen. In general: what lessons has ruangrupa learned in terms of redistributing capital and organising itself to mediate these flows?

farid rakun: Thank you again for having me. It’s not easy for me to be here in London, because since 2022, ruangrupa haven’t been pulled into this type of context where whiteness prevails, and kudos to all of you for making me at least feel like a welcome guest. Because honestly, coming from Jakarta, Indonesia, ruangrupa are in a privileged position that we still have a place to call home. As shitty as it is, it’s still our home. Indonesians don’t have a big diaspora, basically, which is actually a privileged position, so I have to say that it’s not a setting that is familiar to us – I’ll come to that hopefully later.

But because of that, I’m trying to be a good guest right now and I’ve been thinking how to contribute to the invitation to speak here, thinking about what Ibraaz could be. That’s how I understood the invitation. So, I’m going to talk about failure and the capacity to be proud of that, because the capacity to fail is something to celebrate for us and our practice. Hopefully, I will have time to talk about those two things: your question about lumbung – and, by the way, we prefer to refer to documenta fifteen as ‘lumbung one’ – and what we learned as a collective, which relates to failure, because it’s part of a trajectory of what we were doing before and what we’re doing after.

I’m going to start with my own failure. I was born and raised in Jakarta and tried to escape that godforsaken place a couple of times. But I always came back, and a big part of that decision was always the collective, ruangrupa. This year we celebrate our 25th anniversary. Listening to the tech panel ‘Online/Offline’ yesterday, I realised again that we’re old geezers. But we were young once, and we are trying our best to not be old or mature, even though we have to admit that we’re old: so that’s the first failure. The art ecosystem, at least in Jakarta, is not a smooth thing, and this is where things are different as well. I wanted to become an artist from early on, but an artist is considered a reject of society in Indonesia; parents try to stop their children from becoming artists or to work in the art world. So, the elitism of the art world, or art scene, is non-existent. This is not the question we have in my own context. There is also no good art school. I studied architecture but that didn’t work for me. I knew when I was still in architecture school, so I failed that too.

I always feel like we are rejects of society, who can’t function in conventional ways, like in an office, or in formal settings, which is the dream of a lot of people in Indonesia. But I can’t function that way. And with ruangrupa, I realised they also didn’t finish school. They didn’t and wouldn’t be able to work in an office or formal setting; it’s like our kryptonite. We wouldn’t function. And that explains also why we are doing what we’re doing. So that’s the personal part.

Then, we’re also working in Jakarta, a city that’s always on the brink of failure. It’s still magic and still somehow weird that it hasn’t collapsed. Jakarta is one of the fastest sinking places on Earth. It’s just too big. The metro area has a population of around 30 million people. But the city itself only holds around 10 million. So, you can imagine at least half of them commute every day. That’s why it’s not sustainable at all to live there, but somehow it works.

Indonesia is a failed state for me, and I would say that’s why we could exist up until today. Because it has led us to distrust institutions. The reason the founders established ruangrupa in 2000 – when I was a student – was because there was nothing catering to what we were interested in at that moment. There was a market, of course. There are museums, galleries, and all that, but there’s no mainstream, so we were never alternative in that way.

Indonesia is also a failed state in the sense of the trauma of the New Order period, which is coming back; learning from the Philippines, learning from the States, it’s almost the same blueprint. Mostly for us, as Gen X and millennials, for lack of a better word, we failed to prevent the younger people from developing amnesia of what happened in 1998 and before, when it was a dictatorship. Because the dictatorship is coming back, and how are we going to deal with it? Collectivity is part of the answer for us. Maybe it’s not for everyone and we would say that this wouldn’t work for everyone, or for everything. But that’s what we decided to do, and that’s what we know how to do: keep on building an infrastructure where there is none. That’s why we make festivals – we make music festivals, a new media festival, student forums, workshops for curators – when there are none. We were building these things because – coming back to the audience question – we knew we wanted to build stuff for ourselves that related to our interests. So we never had the question: ‘Who is our audience?’; or as David [Velasco] said yesterday, an ‘ideal reader’.

Luckily, we like to make friends, so this ‘we’ keeps on growing. We like to learn from different ways of thinking and doing. Why do we still call ourselves an artist initiative or artist collective? Lately, since 2010, we have called ourselves a collective. ‘Seni’, art in Indonesian, doesn’t translate comfortably or fully to the western category of modern ‘art’, because seni means something that lives in the people, it’s not autonomous at all. The white cube and all that kind of stuff is relatively new for us. Seni is supposed to live in the middle of everyone’s lives, either for spiritual or religious reasons, or social gatherings, and all those kinds of things. But contemporary art, of course, comes from another understanding of art, but it kind of gives us a freedom to do things because artists are considered to be rejects. No one touches artists too much because we’re not that powerful. That gives us a certain type of invisibility. So instead of trying to be visible, invisibility is key as well for our practice.

That relates a lot to what Ibrahim said about audiences earlier. I really relate to that a lot and it relates to certain failed projects. We called ourselves Gudang Sarinah Ekosistem when we occupied a 6,000-square-metre warehouse space for two years, which became too big. Again, space played an important part. It was just not intimate enough, so we were not comfortable taking that space, and we also bled financially so much. But that was the moment when we came up with the terms for our ecosystem, for example, ‘lumbung’ or ‘collective of collectives’. And it ended up in 2018 that we cofounded – together with two other collectives in Jakarta, Serrum and Grafis Huru Hara – something called Gudskul. It’s written like Indonesian slang, but it’s pronounced like ‘good school’ in English.

We tried to make a foray into the informal and educational scene because we should at least, at that moment, cease to be an artist collective because, for one, we are too old, and there’s a risk of hogging everything, from funding and space to concentration and attention. We thought we should become something else. Many of us didn’t even finish school, which we read as the school system having failed us, so we tried to imagine what kind of school would be ideal for ourselves because it didn’t exist. At the time, we planned for ruangrupa itself to disappear, actually: Gudskul should take centre stage. But we couldn’t do it because the invitation from documenta happened around the same time as we established Gudskul. We talked a lot between ourselves, whether we should take it or not. Many of us, including myself, could see too many risks; and documenta as a historical, mythical species has nothing to do with us, so it was actually surprising that they were interested in us.

We decided not to say a hard ‘no’, because in Indonesian language it’s really hard and really rude to say no directly. So, what we did was invite them back: instead of us accepting the invitation, see if they were interested in being part of our journey, with all the risks. Because we were doing something anyway, and if documenta became part of our journey, then the journey would change, of course, and then hopefully it would become enriched at that moment. That was the intention. It was kind of like a way to say a soft no. So, it was a surprise for us when they said yes, actually. I was there when the interviews happened, and I remember one question about our biggest inhibitions. My answer was that we would lose our friends, we would break up – you know, like a band that gets signed to a major label and is asked to make a big, ambitious album and then that album would break the band up. That’s kind of the way we thought about it, and I couldn’t speak properly for a day at least after that, because there would be changes. We didn’t know at that moment what it would entail, what the price could be, because we were so far away from it.

Long story short: I wasn’t planning to talk about documenta fifteen or lumbung one this time because it’s traumatic for many of us. And I’m happy that it hasn’t been referred to that much, or at all, this time, so thank you for that. Originally, what we were trying to do is just install another operating system. It’s clear that the way institutions like documenta have been operating wasn’t working for us and our type of practices. We are not alone; there are different types of contexts, different types of art practices, that are not gallery based, and it’s not for us, so how could we imagine something that would be for us?

So, the governance, let’s say, or the organisational part, is what we were interested in. That’s why we didn’t have a theme. We didn’t put very practical politics at the forefront, but economy and how we do things: invisible work is what we were interested in. We wanted to learn from as many people as possible that are facing similar challenges and that we could connect to. In that sense, that’s why we did what we did. And then politics, topics, themes, and all those kinds of things just came up organically – from queerness to Palestine and, of course, colonisation – not as ticking boxes, but because it’s part of a practice. That’s why artists work like that, because they’re part of a society, community, or context that’s struggling with it, so it’s not forced. And we also didn’t commission. We realised that our question was just: what are you doing now and how can being part of this lumbung journey help you sustain what you are doing anyway?

I think it’s really difficult for an institution like documenta to understand, but we knew it was our job, so one of the first things we did was keep on negotiating. Where there was no artist fee, we fought for it, not calling it ‘fee’ but ‘seed money’, etc. – I could talk about it more if there’s interest in it. Because of that, we realised that the power of an artistic director is very toxic, so we didn’t want to take it on alone. Although we had to realise that no matter how much we wanted to horizontalise it, we would still be seen as powerful figures. But luckily, we were already a lot of people. I cannot imagine what it’s like for those who work as artistic directors alone. No one should do it that way. The burden is too much. It breaks you. It corrupts you. As much as we wanted to share it, we played with it as well; we recognised the power relations, we decided how to make decisions through the ‘majlis’ or assembly, and all those things – the details I can talk more about later.

But because of that, and we didn’t realise it before, we were pre-emptively preparing for when things went south. It’s not like artists only meet when they’re installing, because that’s often the case, ourselves included, when invited as artists to biennials or museums. And then solidarity is forced. When we started meeting, at that moment it’s still on Zoom – again we are not digital natives and it’s super tough for us; but still, the habits were formed. So, when things went really south and the institution that was supposed to work with us betrayed us to a certain extent, we knew very fast what to do. It was not only a burden for ruangrupa – when you attack us you attack everyone else. We never blame anyone that makes mistakes. It’s easy, it’s really easy, when the enemy is clear, then the mechanism works, let’s say.

But I would say in this part, though we would not do things differently, there were two failures. We were thinking, after going through everything, that no one should suffer from what we did but of course it is the case today that everyone is suffering to a different level and extent. We were almost like a warm-up for what was going to happen. The second thing is, it can be read that lumbung one prepared the cultural sector for genocide as a condition; that’s what we didn’t foresee, but how could we foresee it?

Stephanie Bailey: Thank you so much, farid. Ibrahim, I think there’s a bridge here in terms of installing operating systems, governance, questions of accountability, and financial management. And with your work building institutions in Ghana, I would love to talk about how you bridge your institution building practice with your work as a contemporary artist in the global contemporary arts industry. And I’m asking this, bearing in mind how the legacy of Kwame Nkrumah and non-alignment have really influenced your approach to the work that you do, particularly in Ghana.

If you don’t mind sharing, how are these spaces organised, structured, and supported in relation to how you have navigated your practice to build institutions and establish foundations at home?

Ibrahim Mahama: Thank you. Here I am again. I will try to be as brief as I can, so we have more time for discussion. I think it’s quite interesting to be practising as an artist in the global art scene. But then it’s also another thing to think about the practice in relation to the context which inspires or gives birth to it. And I think often in the contemporary art world, for a lot of artists, particularly from the Global South, a lot of the work that we make ends up in a western context. I can count on one hand the number of African artists whose work I have seen in their local context, even those who come from Ghana: you never see their work. Their work is always in an art fair somewhere, either in London or in Miami or in a museum somewhere; anywhere but in the local context.

And for me, in the beginning, one of the things that I realised was there was an inherent labour condition within the objects that inspire us as artists to produce what we produce. So if I go to the markets to collect jute sacks from the market women through a series of exchanges, and I produce a work that ends up in Venice or wherever, the question is: how do we make sure that the experiences or the dialogues that happen in the art world do not only stay in that place but come back to this place? Or not even just come back – why not just make work for this local context?

I have a series of images which I just wanted to make some points with. This is a photo of some colleagues of mine, both older and younger, but mostly younger. They’re some of our students from the university. When I decided to convert my studio to the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art, we were mostly looking at doing retrospectives of older artists, who in Ghana no one knew even existed. We had to work with students in order to build these exhibitions. So again, coming back down to our generation and how we reconstitute our labour in order to excavate the practices of older people.

These are some of my studio assistants and also my colleagues. The guy in the yellow at the back, he’s the artistic director of the institution, and this was one of the exhibitions that we did. When we are building exhibitions, we all just build, we don’t have exhibition installers or whatever. We just come together because we are all artists. I’m part of a collective in Ghana called blaxTARLINES, and we come from the university, from a very intellectual background. But at the end of the day, the point is: how do we bring this intellect together in order to be able to build very ordinary things for the public? So we would work with our colleagues from the university and other places to make workshops. The idea is to build a space in such a way that it also becomes a classroom. And the point was always how to look at the relationship between the work that we are doing and the schoolteachers, because the teachers are also some of the protagonists that we have to pay attention to. And some of the protagonists are also just people contributing their labour to building things within society.

This young man in the photograph in the middle, his name is Zakariyah, he’s our caretaker. When I made the decision to build this studio, Red Clay, which became this big institution, he was living in the community. It was a village, a farming community, where I went to buy some land and start this experiment, and he was one of the people that worked with us. But it’s also very interesting how, in addition to contributing his labour to the building of the physical architecture, he is also one of the key people that gives the tours to the school kids – because most of our programme is geared towards school kids. In one exhibition that we did, we had a collaboration with the ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum in Denmark, and they gave us a loan of a work by Olafur Eliasson. To have this context of Olafur’s work in the middle of a village somewhere, where Zakariyah is a farmer, and he has to find a way to communicate the work of this Icelandic artist to kids who are coming from a formal educational setting, whereas maybe he didn’t go to school – that’s an interesting structure for me. It’s very interesting to me to consider or look at this mode of dissemination.

Or ordinary tuk-tuk drivers. This guy brought two tourists to the studio, and he was fascinated that a space like this existed in his city or village, and he went home and brought all the kids from his house that day. It was during Covid and we were very lucky, we only had one day of lockdown so we could still move around freely and all that. But for me it’s interesting how he, as a character, is someone who has not been to school. Because ordinarily in our line of practice, people are very concerned about the audience. People always ask me this question: ‘Why build this studio in the middle of nowhere? The people are uneducated. They are villagers. They don’t really understand art.’ And I say, ‘What do you understand by art?’ The premise of art is not what we know. The premise of art is always to begin all over again. There is something really radical about art that we have to continuously explore. Knowing that, and thinking that, can open up other forms of courage.

A lot of kids from the villages, when they visit the studio, come in trucks. We realised that there is an entire village that puts itself in this vehicle. When they came to the studio, their truck broke down and they had to push the truck to start it; even kids as young as three or four years old have to contribute their labour to pushing the truck. Here, someone might see it as child labour or a violation, but there’s a difference. I think that’s the constitution of the world as we know it in relation to places: it’s also the sensitivities that we have in how we think about institutions.

A lot of teachers might not want to go and work in a rural community. But for instance, these teachers, they teach in the rural area. And the kids, most of them, their uniforms are torn, so they contribute their salaries at the end of every month, and then they buy uniforms for the kids because the parents can’t afford to. But the uniforms are much bigger than the kids, so the kids have to wear these uniforms until they graduate. So, it’s like a gift, but a lifetime gift – a gift that has to stay with them for a long time. So, in thinking about this idea of gifts, I also like to think about the gift of the work that we have to do as cultural practitioners. Some of these images are just looking at the relationship between, let’s say, our audiences, the kids, in relation to their teachers and how, when they come, the teachers have to translate because education has also declined quite a lot. So, even though Ghana is an English-speaking country, when you’re interacting with the kids and then you speak English, it’s very difficult for them to understand. So, the teacher who is supposed to be teaching them English in school has to now translate into a local language for them. Although it might be seen as a defect, I also find it very interesting to think about.

The kids in the community are also important when it comes to thinking structurally. We make the programme and the structure so open that the kids are always there. When we are installing exhibitions, we take them through the exhibitions. People from the local community are important, even the security men. At any point in time, when someone comes to the space, anyone in the community should be able to have a dialogue with them through the things we have collected or the exhibitions.

One of the things I wanted to stress was the women in the local community who bring their kids. Because they always come on a motorbike, and sometimes their kids might have been there with a school, so they will take them around on a tour. But it’s interesting, when the women come again and again, they become these people that begin to translate the conditions around the work to other people within the community.

These are the last two images. You can see some women carrying plants and then the other woman is carrying these local drinks. Again, there’s this local woman in our community who sells fruit, and she always comes around the institution, and when there are people walking around, she walks around with them, and if someone wants to buy mango, she puts the mango on the installation and she rips and cuts the mango. So there’s a sense of a business transaction that is happening there. It’s important to think that in a traditional or modernist context of art making, she would have been the object of the work, a figure in a painting which would hang on a wall. In such a context, the idea of the artwork’s surrounding conditions, together with the labour, does not go into the context of the institution.

I think this is one of the things that we really have to consider, because for me, that’s one of the things that I learned quite a lot going through the art world. It’s always about the point or the question of dissemination. I think it’s one thing that we still haven’t quite figured out. I always get frustrated when you go to museums, and then 95 per cent of the security or the cleaners are minorities, and 95 per cent of the audiences are white, middle-class people. It’s funny, when I go there and walk around, sometimes these security men are looking at you like, ‘What are you doing here?’ Like you are up to no good, you know? And it’s interesting. So, I always ask myself, is it that the kids in Brixton or in Peckham, or somewhere in Deptford or wherever, are not interested in going to the Tate, or is it the organisational structure?

I think we should open up the organisational structure around how art is constituted, what we think of art amid this precarity, because we also have to come from a point of acknowledgement of the existing truths in the world. The world is a really fucked up place, and it’s so unequal. And we have to start from that point of realisation and knowing that, indeed, this is the system that we come from. How do we produce using that system as an ingredient, so that we make sure that the images it creates afterwards are totally different from what we inherited? I think that’s why in most institutions they can have very generous funding and all the other beautiful things, but it still seems like it’s very disconnected from the world that we’re living in.

Stephanie Bailey: 100 per cent. And what I appreciate so much about the work that you do, Ibrahim, and what ruangrupa does in Jakarta, for instance, is that you are doing the work of instituting, right? Like, it’s not even a question. It’s just about doing what has to be done effectively given what is required in that context. What knowledge do you have to apply to test out what’s possible? I love what you said about the promise of art being to begin again, or that we don’t start with knowing the final outcome. What’s the point in having the conclusion already? Then you might as well not begin. The point/aim, as you said, is to go forward and to see how things grow organically.

But I’m curious, farid, how would you describe the organisational ethos and structure of the work that you do? For example, Gudskul is a collective of collectives, effectively – how do you manage it? I wouldn’t imagine it’s like a solid internal structure, right? It changes. People come in, people come out. Whereas with you, Ibrahim, I imagine you have people that you work with on the ground who are there, and they take care of the work. So, in a few words, would you describe the work you do as organisational?

Farid Rakun: We realised that we are ungovernable, and we are keeping it that way. Whether we want it or not, there will be power dynamics, there will be leaderships. Organically, it will be introduced anyway, and we have to address it. But we know that we wouldn’t be able to know beforehand what those dynamics will be, or prepare for it. That’s why, at least for us, I think it’s still very important to be in one space, share space, waste time, because then we can address certain dynamics, unsaid things, and understandings that occur and strategise around them together.

Ibrahim Mahama: I guess for us we try to be very simple in the way we run the institution: how to intervene, but at the same time, how to open up to the public as we are doing it. We have an artistic director, we have librarians, we have different people that will work within different capacities, but the point is also to make sure that the dissemination of the work, the core part of the work, stays with everyone within the institution. So, it’s not only the responsibility of a few people. You could be responsible for waste management, but fundamentally we are all working because of one thing, which is the work. So that work has to stay with all of us, and we all have to find a way of distributing it.

Just these last couple of weeks, we have been reinstalling the permanent collection in one of the spaces. And sometimes, like in the earlier images I showed where we invite the school kids, they come to see us installing a work which is part of a public collection, which they’re going to inherit. But the question that I ask myself is that, when we are installing it together with our team – the artistic director and everyone else, maybe the cleaners – and these kids are there witnessing that there are no hierarchies, what does that mean ideologically? How does that really structure their mindset? Those questions are very important.

Stephanie Bailey: Thank you. So, there’s a reason I had Jaya as the final speaker, because I feel like Jaya [Klara Brekke] is going to really bridge quite a lot of what we have heard. I’m so curious because we are so lucky to really have a systems thinker with us. So, when I asked Jaya about what she was thinking about discussing today, Jaya wrote ‘the pros and cons of decentralised organisational models or perhaps more poignantly – technological infrastructure, epistemological, and organisational sovereignty’. My reply was a prompt: Is it possible to bridge both?

Jaya Klara Brekke: Thanks. I’ve been listening very carefully to the previous two presentations in a curious way, and what I was thinking to talk about was also very much about failure, and also very much about curiosity, exploration, and courage, which Ibrahim touched on. But firstly, wow, the past day has been incredible. I’m truly humbled to be sitting here with people that have such incredible practices. I come from a very different world. The tech industry is a very different kind of space, and seeing or being amongst people that really put human beings at the core is a huge relief. Where I come from, key performance indicators are at the core instead. So, I’m very happy to be here and I hope that my contribution will be of some value. I think Ibraaz is such an important intervention right now, being in this kind of heart- and mind-breaking situation where you feel quite powerless in the face of genocide and rise of tech-fascism.

I think I was probably invited because I’ve spent the past 15 or 20 years thinking and working on the topic of power dynamics as it relates to technology and decentralisation. I used to see these two topics as potential vectors or levers towards more empowering and equitable organisational models. I have to say that my personal experience – and I think the global and historical experience – of that has failed massively and I want to talk a little bit about that.

But first, a bit about what I’m doing right now. My background has been in academia and now very much in the tech industry. I work for a company called Nym, and what we do is we build very strong privacy technology and censorship-resistant communication systems. I thought I’d mention that because I think that’s relevant for a lot of people here in the room, especially as I know a lot of you are also involved in activist organising and come from places where censorship has been rampant, or where everyone is experiencing, as in the UK and the rest of Europe, censorship ramping up. We are very much hoping that these tools are going to be helpful for people down the line.

I also mention it because this session is about organisation and at Nym we do have quite a curious organisational structure. It’s a bit of a Frankenstein, to be honest. We are founded on a technology called blockchain, which allows for a certain decentralised governance model and also a certain kind of decentralised economic model. But we also are a company that’s incorporated in Switzerland as a ‘société anonyme’. The people that are in the company come from a variety of backgrounds that include typical tech corporate backgrounds, and others have also been active in various types of anarchist collectives and the military. So, all of that makes for quite a wild organisational structure, where we are trying to take the best from all these different worlds and do something effective with them in terms of protecting the right to privacy – as the basis for a democratic society.

On the topic of blockchain, this is one of my theoretical engagements also. I wrote my PhD in the early days of blockchain: it was a political analysis of the Bitcoin and Ethereum protocols. This is one of the first failures on the topic of technology and especially peer-to-peer and decentralised technologies. Already in the very beginnings of blockchain, it was pretty clear to see how certain things could go wrong. It was clear that the architecture itself was a hyper-financialised architecture and that would open it up to exploitation around market manipulation and also the types of subject formation that goes along with financialisation, which basically encourages everybody to really have this quite dumb behaviour, right, where you will click buttons, and do various basic things in exchange for some lottery tickets, which is effectively what crypto is. It was also quite clear that at the core of blockchain technology was a kind of technological determinism that is pretty rampant and hardcore.

On this topic of technological determinism, I think one of the things that’s become very evident, more broadly speaking, in the world of technology today, is that technology has moved on from being a set of tools to actually becoming an ideology in and of itself. There’s pretty much a literal coup happening in the United States right now, where the ‘broligarchy’ is taking over the government and basically dismantling institutions from the inside, quite explicitly, and a lot faster than I had anticipated. But also, it’s important to recognise that this has been building up for quite some time. A lot of people have been writing quite critical pieces around Silicon Valley ideology and libertarianism, and in blockchain you really see that on steroids. So, I wasn’t entirely surprised when Trump launched TrumpCoin, and to see the takeover of that space.

The other thing that’s important to recognise with technology, having moved from a set of tools into an ideology, is the deep integration of networked infrastructures into people’s everyday lives that’s happening right now. Like a very deep integration. Which means we use our phones for literally everything, so that’s why it matters so much that we understand how these ideologies are actually affecting things from the inside. When it comes to the offline/online thing, I was thinking about it from a basic User Interface perspective that, at the end of the day, people have much more ongoing engagements and touchpoints with these corporate platforms than they ever do with any democratic institutions. Like, how often do people go to a town hall? People aren’t going to libraries as much as they used to. People aren’t engaging with public institutions.

On that very basic level, the touchpoints of people engaging with institutions versus people engaging with technological platforms has shifted radically. This means that the glue holding society together as a kind of common substrate and a common set of protocols has also shifted into tech platforms. Let’s say the explicit coup that’s happening in the US right now has been long in the making, and there is a much more subtle coup that’s happened in people’s everyday lives. There’s obviously flip sides to that, right? There are the early days and the dream of what network technologies and the internet could do at an emancipatory level, which is absolutely not how things have panned out today. So that’s definitely one failure.

The other thing I wanted to mention in relation to technology is weaponisation. With this deep integration of network technology into our everyday lives, we have also seen weaponisation of our personal data, through algorithms, for commercial purposes. But increasingly that is also going to be for militaristic purposes, and that’s super important to recognise. This is no longer an abstract threat or paranoia. It’s very real. The pager attack by Israel in Lebanon, for example, was a pretty explicit example of that.

So, what happens in response to these two major trends is we’re also seeing a grappling for integrity across scales. That’s happening at the personal scale, where people are trying to put their phones away and there are various self-help situations; and on the macro scale, at institutional and national levels, the main topic right now is how to regain technological sovereignty.

On a more positive note, with the opportunities within the tech space right now, we are also seeing a decline of US tech supremacy in a weird way. Going hand in hand with this spread of ideology and weaponisation, the speed at which it’s happening right now also means that people are starting to see the US as actually kind of parochial, as in: ‘Wait, they have their own interests and they’re over there doing all these very strange things that no longer are very easy to relate to for the rest of us.’ Of course, China is the major competitor coming on the stage with new AI tech and so on, but I think beyond China, this decline of US tech supremacy does open up a lot of space for new voices, new experiments, and radically different perspectives on technology that come from a different set of people. I think there’s an opportunity there for interesting new conversations on the role of technology in society.

The other thing I wanted to mention is there is no single expert in the room, due to the fact that technology has become so complex and deeply embedded in everyone’s lives. It means there are so many different touchpoints on technological infrastructure and how it affects us as human beings and as society. And I say this as someone who works with cryptographers and engineers every day and they have no clue about how the technology that they build is affecting the world. They have their niche little expert realm. And I want to mention this because I see that there’s a tendency for people to feel a bit disempowered when it comes to speaking about technology and feel they maybe don’t have the expertise. There’s relevant expertise at all levels of the stack and at all different touchpoints. It’s really about understanding and recognising the real-world effects of these infrastructures that we are building. That means that I consider parents, teachers, trade unionists, disabled people, workers across industries, and old people all experts on how emerging technologies are affecting their lives on an immediate level.

Finally, this topic of curiosity that I brought up earlier, when we are looking at failures: I think it’s a very sweet human tendency to freak out when things fail, or when things don’t work out the way they are supposed to, or when things start to get really difficult and you want to just get rid of all of it. But I think staying curious in the failure is such a powerful move, and it’s one also where I think culture really wins. I’ve seen this again in the tech industry. Some of the most interesting voices for understanding how the big technological changes that we are going through right now affect us as human beings are artists. They are the ones that are trying to understand what it means to be human in relation to artificial intelligence, to global financial systems, to strange blockchain systems and encryption and quantum computing, and so on. It’s really artists who are at the forefront of understanding this question.

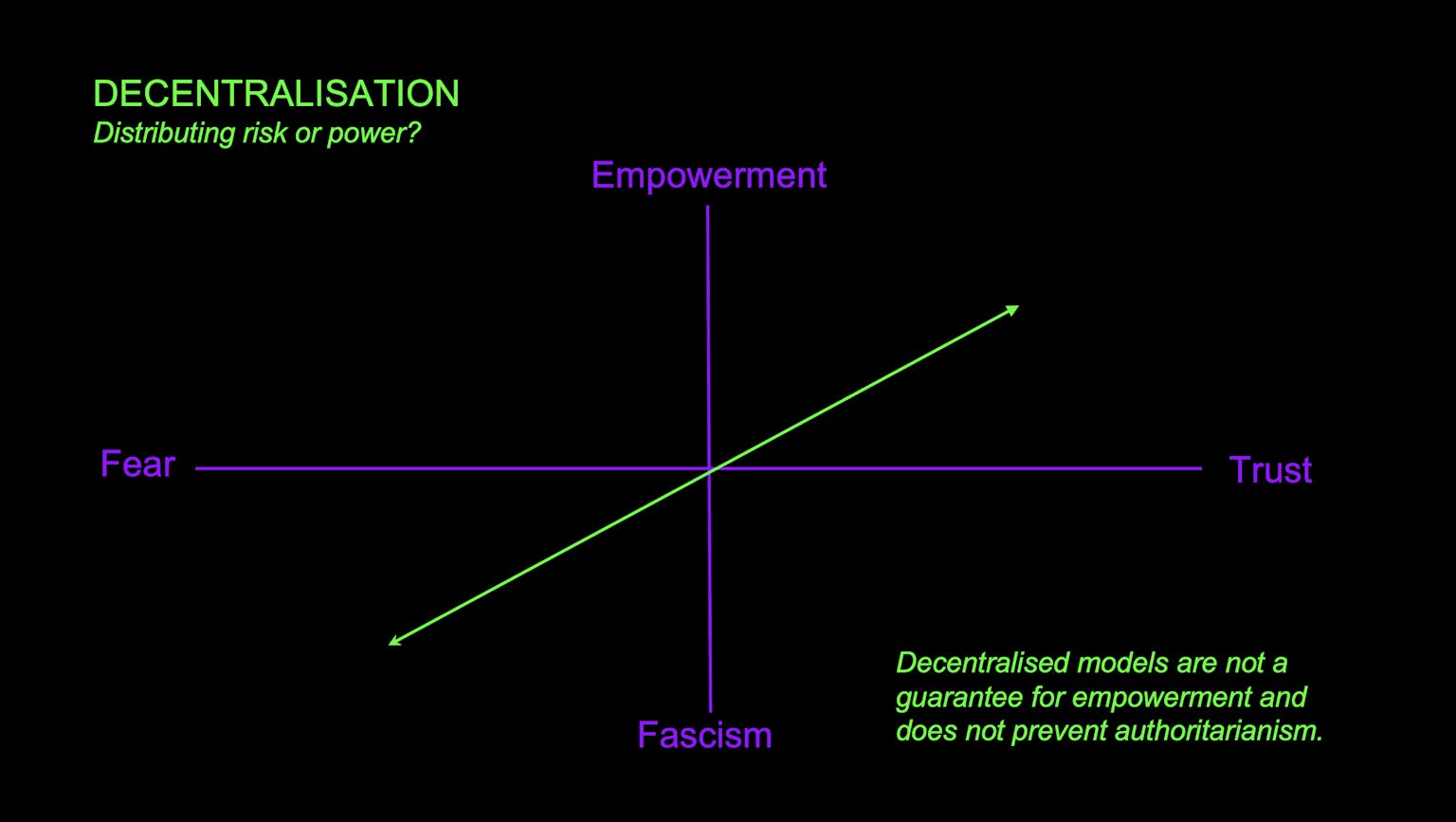

So, the second failure is on the topic of decentralisation, which is something that I’m grappling with right now. As I mentioned, Nym has a blockchain component. What does that mean? It serves a bunch of technical, gnarly things that I don’t want to go into right now, but it improves privacy radically. It also does another thing. It allows us to issue a token, which means we have a lot of stakeholders who own a part of Nym and will benefit from the success of Nym, so to speak. The question that we are sitting with a little bit right now is that these tokens can be used economically, but they can also be used for governance. We haven’t fully enabled that and there is this question, I think, regarding this concept of decentralisation: when are you actually decentralising power by including people in governance? And when are you actually just decentralising risk by placing the burden of responsibility and decision-making on others? That’s quite an important question, I feel, that often gets bypassed on this topic of decentralisation. Accountability is the actual question that should be asked. Who is accountable for decisions? And can they be held to account by everyone affected?

The graph that I’ve put up is one that I’ve also been thinking a lot about lately. The topic of decentralisation has been a little bit of a dream, in terms of how to organise the world in a way where we can be assured that fascism will never rear its head, that authoritarianism will never rear its head. There’s been an attempt at establishing democratic institutions and decentralising the decision-making process around who our political leaders should be. We have seen those institutions, in fact, elect fascism. So, there is a failure there to reckon with. Then markets have also been perceived by some as a kind of anti-authoritarian move, where markets, as a kind of decentralised pricing mechanism, can counter authoritarian political decision-making. But again, we see how decentralised markets give rise to hugely centralised economic power; so, again, a massive failure. We have seen this in decentralised networks like the internet, and, as I was talking about earlier, blockchain, where we have seen multiple failures.

But that doesn’t mean that I think we should give up on decentralisation per se; I think it’s interesting. But what I am trying to say here, which is a very important lesson that I learned, is there is no organisational guarantee against authoritarianism and fascism. You cannot build a perfect protocol that will be a final solution, no pun intended there, on how to blueprint society and then you are done. It just doesn’t work that way.

What I’ve noticed both on a micro level in my organisation and on a larger scale, is this graph seems to hold true. As in: in an environment where fear and suspicion grows, decentralised structures in fact lead very quickly towards fascism. In an environment where trust is built and continuously maintained between people and the institution, that’s where you see decentralised structures really blossom into a condition of empowerment. For me, the question is no longer to find the perfect model. The question is to make sure that trust continuously gets built, continuously gets maintained. And that is what I see as more important.

Stephanie Bailey: Thank you so much, Jaya, a really great way to conclude – trust is really the metric, isn’t it? Which relates to our next panel on the question of measuring relevance and success. So, we have 15 minutes; everyone who wants to make a comment or a question, please hold up your hands and we’ll throw the mic around.

Al Hassan Elwan: Thank you to the panel for all the great insights. I wanted to ask Jaya about the coup that’s happening in the US and the idea of the ‘broligarchy’ taking over this dream of decentralisation. Is there an actual game plan for that to proceed effectively with current technologies?

Jaya Klara Brekke: I don’t think they have an aim of decentralisation per se. It’s more like the ability to exploit decentralised systems that have been built. I mentioned this a little bit in my comment to your panel yesterday: I think market manipulation is definitely something that we are seeing continuously. That’s taking advantage of markets and also taking advantage of the platforms they have; it’s easy to ping signals that have a huge impact on market dynamics. That’s definitely one of them. But I think their plan, from what I can tell, is pretty clear. It’s literally: destroy the institutions and grab as much power as possible in the process. One thing I didn’t mention is, when I say technology is an ideology, I really mean it quite strongly: it is the idea that humans are fallible, but maths is not. That’s literally how these people think: that tech is infallible, objective, and clean, while humans can lie and should not be trusted, even with the governance of themselves. So, the agenda is literally: replace humans with tech as much as possible.

I’m very against this human versus tech distinction. It’s a total fiction that just doesn’t make sense. As humans we create technologies and technologies shape us in turn, and that relationship has always been the case. That’s the way that ideology is playing out basically. This is not a situation of humans versus machines, but of humans and their markets and machines literally mobilising to kill other humans and destroy their ways of life.

Muhannad Hariri: Something to link the two: farid, you said something that really struck me, which was that you have to figure out who the enemy is and that way, when the pain comes, it’s kind of shared and there’s no infighting. If I understood you correctly and if I had a chance yesterday, I would have said I would have liked to hear the word ‘evil’, because the other side loves to use that word in very uninformative and abusive ways. But people don’t like the word evil because it has a long history of abuse and a religious connotation of demons and devils and stuff like that. My research is on secular evil and how to think about that productively, politically, and ethically, and I have an anecdote to clarify why I find this so interesting.

I was in Beirut when the pager attacks happened. I was actually teaching, in a room full of students, and suddenly we felt – like a lot of people in Beirut – like, we are 20 people with 20 potentially explosive devices. We all really felt quite frightened, especially when the news was first coming out. It was like four in the afternoon or something like that. I remember just hearing sirens everywhere. I remember total chaotic panic. I remember two students who actually received a phone call that relatives were harmed, and we just didn’t know what was happening for a couple of hours. I posted something, because I started seeing the images, and the images struck me in a very strange way. You keep a pager or phone in your pocket, on your side – and this is something Zionists love to point out, like, ‘We blew their balls off’, kind of thing. Really awful jokes.

But even me, I’m looking at them as these extremely intimate explosions taking place on the bodies of these people who are in supermarkets, on the street, on motorcycles, and I just posted the sentence: ‘Beirut is on fire with thousands of these intimate explosions on people’s bodies: it’s like we have telegrammed you a bomb.’ Now, ‘intimate explosion’ – you can understand that in a different way. I had to stop posting. I turned my phone off for like three or four days because of the hate that I received in my DMs from people who were like, ‘I always knew you were a closet Zionist. I always knew that you were anti-Hezbollah.’ Because Lebanon is very complicated and you can hate Israel and hate Hezbollah and not be a square circle, you know?

That experience taught me like, well, I’m not your enemy. I didn’t plant these bombs. I used language maybe in an infelicitous way, maybe in a way that you are projecting a lot onto. But I was also scared, I was also concerned, I was also frightened. And that’s the thing: inside Lebanon it has been so difficult. Who is our enemy? How do we articulate that enemy? And how do we do it in such a way that doesn’t make more? If you see me on Instagram whenever I post, ‘Don’t make more enemies when you already have enough’, that means I’ve had a bad few days in my DMs and I go offline because people are abusive, I think, to the wrong person. And the infighting. And from a governance point of view, that goes back to the discussion yesterday about Ibraaz, and who is Ibraaz’s enemy. We shouldn’t be shy about formulating that.

Declan Colquitt: Thank you. The past few days have been absolutely amazing. We have spoken a lot about who or what Ibraaz will be beholden to in terms of its autonomy. But also, it’s important to talk about Ibraaz’s power, and the people who will be beholden to Ibraaz in terms of being employed by them. And also, just to maybe set some expectations, Ibraaz has the chance to do something in terms of its internal structure that some people would call radical, other people would call a bare minimum, and other people would just call common sense. So, here’s a series of questions:

Are you going to somehow codify a commitment to a time period within which you promise to pay invoices with external practitioners?

How much are you going to pay your staff?

Will your front of house team be separate or beneath management in terms of your internal structure?

Are you going to allow staff to grow into their roles?

Will the structure allow for progression and growth?

Will any of your staff be on a zero-hours contract?

Will you encourage them or allow them to join a union?

Will your cleaning staff be in-house or will they be outsourced?

If front of house staff are invigilating in a gallery, are they allowed to read? Are they allowed to have their phones?

By the way, this is framed as someone who worked five years in a museum as an education facilitator, so if they seem incredibly niche, they are based on experience.

How long are your staff dinner breaks going to be and will they be paid?

How long will maternity and paternity leave be?

Will your staff operate on a four-day week?

Is the general public allowed to come in here and just be? Can they come in here and work?

What will you do when people are rude and abusive to your staff, particularly people in the café? This will happen, and probably by people you consider friends and people that you like.

Are you planning an education programme? If so, will this programme be affordable and accessible within school holidays?

Will the gallery have a dedicated session for new parents? At the previous place I worked at, we called this ‘Gallery Babies’.

Will the gallery have a dedicated time or space for people with autism?

Will you screen things in multiple languages? Will your exhibition literature only be in English?

And what are your expectations of your visitors? Will you have a code of conduct?

How do you feel about people coming in here and using this space as a warm bank?

Now, I don’t expect Ibraaz to be perfect and do all of those things because praxis and theory are different and Ibraaz isn’t going to be everything to everyone. But I would hate for us to have had these amazing conversations and for Ibraaz to be platforming these important discussions, and then for us to find out that there are zero-hour contracts. That would break my heart. So, all the common-sense things that you can do internally as well as the radical things that are also done – please do those as well.

Oscar Guardiola-Rivera: Impossible act to follow. Those are the correct questions. I have therefore two very silly questions. Question number one: what does the panel think about the tension between horizontality and verticality as a design or framework for designing governance and institutions? We already heard about the tension between central and decentralised, and of course now we are learning that the dream of decentralisation is the dream of neoliberalism is the dream that ends in techno fascism.

Second question: the tension between quantitative and qualitative, which was also mentioned in the panel. On the one hand, we know that the dream of harmony, by calculation, is not new. It’s as old as the ancient Egyptians or the ancient Greeks. Of the Greeks looking at the sky and thinking you could model society or institutions on the fixity of that geometrical model. What has changed now, therefore? What is different that we would need to begin again?

That’s the other tension between the promise of art, as you put it, Ibrahim, beginning again and the reality of museums, institutions, and – of course, Françoise knows this better than most of us – the so-called universal museums, which promise the exact opposite: permanence, perennialism, continuity.

Jaya Klara Brekke: Thank you so much. Honestly, when I was preparing this, I didn’t really know how practical or theoretical to go. Then I kind of followed the tack of the past day and figured, let’s do the spiel. Obviously, I have a lot to say on technical infrastructure and so on and so forth. Harmony through calculation, yes. What is different now? Although, I don’t know – I’m not a historian, so it’s hard for me to say exactly how different it is now – but it seems to me that there’s a certain kind of hate for humans that feels quite unique to this moment. And it also comes hand in hand with the fascination with artificial general intelligence and so on. So, there’s a specific tech industry ideology that is definitely pulling on some of these longer-term trends but has taken a very specific form right now where it feels like there’s a certain kind of hate for humans at its core.

Then on horizontality versus verticality, again, it’s a question that I grapple with daily. In an earlier phase of my life, I was mostly involved in horizontal organisations, and I now have the fancy title of Chief Strategy Officer at a company with a hierarchical organisation. I’m a manager and I manage a large team. And this question of what it means to be an anarchist manager is a very strange space that I’m still kind of trying to work out. It’s also where this topic of trust is very important for me, in terms of how I’ve kind of squared that circle for the time being. Because as a manager, you have to hold that space with full responsibility and accountability, and that is a potential benefit of the vertical line, in that authority becomes clear, so people know who to hold accountable. When authority is not clear, that becomes a lot more murky and can open up a space for abuse of power also, which I’ve seen time and again. So, I don’t privilege horizontality over verticality. I think there are benefits to both, and that needs to be designed and thought through very carefully.

Where horizontality becomes very interesting is in this question of trust and empowerment. In my position on the vertical line, my daily practice is to empower the horizontal line, to create horizontal dynamics. There’s an anarchist theorist that passed away recently, David Graeber, who talks about the relationship between the teacher and the student as a relationship of power, but it’s a relationship of power that negates itself. Meaning, if you are a good teacher, your student will surpass you. I try to maintain that philosophy.

Farid Rakun: Thank you for all the comments. In terms of horizontality versus verticality, I’m going to talk in analogy. It’s not perfect, but one shortcut that has been useful for us is actually ‘total football’, because it’s both. A goalkeeper can be a striker, but it demands certain things: the dynamic between the group, but also everyone needs to be a generalist and good at everything. And wasting time with each other – there’s no, at least in our experience, replacement for it. And thank you, Declan, for listing those questions just now. When we work with anyone, we first ask the institution to show us their Excel sheets just because curatorial texts and all those things can sugar-coat what is in the Excel sheets. Where are you going to put your resources? Up until today, I can say we haven’t seen the Excel sheet for documenta fifteen.

Radha D’Souza, Rasha Salti, Anne Barlow

Ibrahim Mahama & Shumon Basar

Alia Al Ghussain and Matt Mahmoudi, hosted by Jaya Klara Brekke