- Mission Statement

6. The Organisation: On Governance and Structure

farid rakun (ruangrupa), Ibrahim Mahama, Jaya Klara Brekke

Mission Statement 00: Why Now?

This is a lightly edited transcript of the fifth session of Ibraaz Mission Gathering 00: Why Now? which took place on 21–22 February 2025.

Panellists: Ibrahim Mahama, Sumayya Vally

Moderator: Dima Srouji

Respondents: Muhannad Hariri, Shumon Basar, Oscar Guardiola-Rivera, Taghrid Choucair-Vizoso, Adam Broomberg, Taous Dahmani, David Velasco, Evan Ifekoya, Nadja Argyropoulou, Sam Samiee

Shumon Basar: Our first session today has a deceptively simple, but I think important title, which is ‘The Building’. The reason to talk about the building presents itself the minute you arrive at 93 Mortimer Street, and especially as you walk through that door and enter into this room. Many people upon entering here for the first time have lots of different emotions – quite extreme emotions – and in a way, I think those extreme emotions in relation to architectural language, architectural history, the history of colonial language vis-à-vis architecture, etc., are something we need to address. The way we are addressing it is by inviting and appointing Sumayya Vally, an architect from Johannesburg who’s also based here in London. Sumayya was the architect of the Serpentine Pavilion in 2021 and is now working on many projects across several continents. We also have the Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama, and moderator Dima Srouji, a teacher at the Royal College of Art and an artist, architect, and researcher. Will you please join me in welcoming our guests for this session. Thank you.

Dima Srouji: Thank you. It’s a pleasure to be back in this building with you all. I’m excited to have a chat with Sumayya and Ibrahim. Yesterday was, I think, overwhelming for a lot of people. It was exciting and frustrating and worrying and hopeful and positive and negative – with ups and downs throughout the day. All of that happened in this building. And as Lina [Lazaar] said on the first day, it’s important for us to be in a physical space together to gather, to have these feelings, at the same time. Architecture has the capacity to do that, and physicality, the act of gathering, is at the core of this mission. At its foundation, architecture is about refuge, shelter, enclosure, protection. Yet it also has the capacity to harm. In Gaza, it is often the building itself that kills, if you will. The mounds of rubble are no longer just remnants of destruction. They have become cemeteries waiting to be exhumed. Public spaces, cultural centres, schools, and hospitals – once sites of service with clear functions – have been forced to shift their purpose. Instead, they have become domestic spaces, places of refuge, phone-charging stations, and sources of running water.

But most importantly, they’ve become spaces where social intimacy creates safety rather than the buildings themselves. This is a sign that architecture has also failed us. How can we repair the discipline? And what does it mean for us to inhabit spaces that have violent histories? Is it actually the architecture that gathers? Or can this gathering happen under any other roof? Spaces – the walls, the roofs, the doors, the fireplaces upstairs – they hold within them intergenerational memory. Their function fluctuates. They have always been dynamic. They are containers, vessels of lived experience. And yet, architecture has long been used as an instrument of power, one that erases, excludes, and enforces violence.

We can’t sit here in this space without being confronted with its history. But we also must recognise that architecture is built for multiple generations, and perhaps we have the right to enjoy the glamour of this building and seek pleasure in it, as David [Velasco] said yesterday. As uncomfortable as that makes me feel, we also should have the intellectual honesty to say that this really is a beautiful building. Sumayya’s practice directly confronts this history. She searches for new ways of making, ensuring that architecture does not simply replicate a western lineage, but instead speaks for those of us who have been left out of its canon. Her work is an interrogation of power, and a reimagining of what architecture could be if it served us differently. Ibrahim, known for his work as an artist and for his installations, is also deeply committed to his community and has built multiple institutions through his projects in Ghana: The Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art, Red Clay Studio, and the Nkrumah Volini (an artist-run space that functions beyond the traditional boundaries of the art world). They serve as sites of education, collaboration, and experimentation, and are deeply rooted in and committed to the community. So, we have a lot to learn from you as well.

Both Sumayya and Ibrahim challenge architecture’s role in shaping histories and futures. They resist its limitations, stretch its possibilities, and reclaim space as a site of collective agency. So, we’ll begin with Ibrahim’s presentation, and then we’ll follow with Sumayya. Then the three of us will have around 20 minutes to speak to each other, and following that, we’ll have 20 minutes for questions from the audience. We’ll start with you, Ibrahim.

Ibrahim Mahama: Thank you. I was wondering what to speak about in relation to the building – the idea of the building. Because for me, there are so many things that come to mind when we think about what an artist – what the idea of an artist – is supposed to be. I come from a traditional art school that was established by the British back in the 1950s, which was very conservative. It ran for many decades until the 2000s, when a group of young professors decided to radicalise the programme. It was at this time that I became a student, and I was a beneficiary of these changes. These changes were more or less about thinking about capital at the same time as thinking about art – thinking about the contradictions of art itself, but also ultimately thinking about art as a gift. In Ghana, we’ve not really had a lot of interesting architectural histories. Not even from the colonial period to the 1960s and 1970s, when a lot of buildings were built – especially in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The image you see on the screen is one of the buildings that was built by Kwame Nkrumah together with the Soviet Union. At the time, the Soviets were aligned with Ghana because Nkrumah was a socialist. He had a lot of collaborations with engineers, architects, and builders from the Eastern Bloc, and one of the things that he was very interested in was the idea of building grain silos for storing food, because the British had built the railway for the extraction of commodities. Nkrumah said that economic independence is the true way forward. Fast forward to after the structural adjustment programme, and most of these buildings were either privatised or sold. They couldn’t be demolished because they were too massive. There was a lot of propaganda, of course, at the time when the CIA overthrew Nkrumah. There was propaganda that he had built these buildings as nuclear silos, because Ghana was also part of the Non-Aligned Movement during the Cuban Missile Crisis. My father studied architecture, but no one in that generation has ever had any relationship with these buildings, and there were so many of them around the country. They’re like these visible ghosts. You see them all the time. You see them, but you don’t see them. You don’t even question what is this for? I thought that we – as a generation, as artists – have to intervene.

This is what I did by reinvesting the capital that I acquired as an artist into renegotiating and buying some of these buildings in order to reopen them for a younger generation. Working with young people, my aim was to re-excavate these buildings and then try to make them accessible to various audiences. The excavation process is very important to me, because sometimes, in order to be able to make something accessible, you have to scoop it out. My background is in painting and sculpture, and I like the idea that you have a clay-like material that you’re scooping into in order to reveal something.

In the building, there was a very different ecosystem because it had not been inhabited for almost 60 years. It contained bats, snakes, and owls. Most of them, except the snakes, of course, still live in the building, and the idea was to find ways in which we could intervene. For instance, inviting artists to do interventions within the building while being sensitive to the chief protagonists of the building: the bats, the owls, and the ghosts. The ecosystems within those spaces actually should be the first audience. But I was also thinking: what can we learn? So as an artist, going back to it, I went back to the railway, the history, the architecture – everything.

A lot of this also comes back to the question of labour, because in the Gold Coast, most of the labour that was used in building the railway for the extraction of gold for the British Empire came from the north – from Ghana, from Nigeria, from Sierra Leone, as well as other places. At the time they were paying them the same as they were paying the men they took from West Africa to fight in the war in Europe – it was one shilling a day or so. All these rail lines were built in the Gold Coast.

Of course, our governments over the years have had this habit of where, if something is old, it’s discarded – as in many places. So, I think of myself as something like an organ harvester. I didn’t kill the body – I just go and harvest the organ. I intervene and I buy these things, and then we rebuild them in places where they can be reconstituted as a different thing.

When we are building, we invite school kids to see. Even when we are doing installations or building the architecture or the building itself, the point is that it’s like an archaeological exercise. There’s an ideological thing that we are excavating, and all those memories are embedded within these objects, which normally would have disappeared. I do this even with objects like airplanes. I buy these old airplanes and transform them into classrooms. What does it mean to teach children coding in an airplane, in a rural area which normally is out of sight within this context?

This is the Parliament of Ghosts, a project that I developed for the Manchester International Festival in 2019. We worked on it for two years, and the idea was to take the remnants of British colonial history to Manchester in order to reconsider the legacy of the Industrial Revolution and think about how to rebuild it as an architectural form. I like the idea that you can build a work as a theatre, as a stage, but I’m also interested in the constitution of labour within this space. So even when we are building, the kids in the community are using it as a swimming pool because it’s gathering water. We are using the same water to build the space. Whereas maybe in traditional architecture it’s very difficult because once a building has been built, everything is sealed off until it’s ready to open. But I think that making art should open up a space which allows for many different possibilities to happen. Here you see that even as we are building – as the bricklayers are building the space – the kids are there. It’s almost as if they are the ones who commissioned us to build this space. It’s like they’re coming from the future to give us these commissions. You realise the teachers are doing workshops with the kids in the building as we are building.

I like this idea of having different communities using the space, such as working with high schools and giving lectures. How do we combine with the world outside? We work with the local women in the community to plant things, while they’re also looking at the archives within the building which have been constituted over time. Or we even use straw, which is used in architecture, and think of it, like the bats, as a protagonist within the architecture. When you come to West Africa, for a lot of the mud houses they weave together this straw and use it to build the walls and sometimes the roofs and other things. I like the idea of using these very ordinary raw materials, which normally people associate with poverty, as characters within the constitution of the building or the architecture. The local women that we work with, and the studio assistants, they are the first audience and sometimes the only audience. Someone might say – because in the art world people always say it – ‘but who is seeing the work?’ And I say, ‘what do you mean, who is seeing the work?’ When labour is making something, there is a confrontation there which I think can be interesting.

This image is one of the current works in the parliament in Ghana, where I was looking at this idea of taking the sticks that the women gather at the end of every year when they burn the grass in order to replenish the soil. When the rains are about to start, they make barriers in the farm, so the farm animals don’t come and eat the seeds and other things, so there’s a lot contained within these materials. I also like this idea that, even in this sense of looking at portraiture, we can think about it in relation to, let’s say, these forms.

Sumayya Vally: Thank you so much. I am very intimidated, I have to say, to speak amongst so many people I respect and admire. In thinking about the building, I wanted to introduce my practice to all of you and also leave us with a few prompts to get the conversation going. My practice is called Counterspace and was started in Johannesburg as a collective practice with a group of friends during our master’s degree year at university. It was really started as an initiative and as an endeavour to express and pour our love for our city, Johannesburg, into a research space. Studying architecture in Johannesburg, we became aware of how much our city was shaped by segregation, and how much that segregation was an act of extremely intentional design. Of course, it’s by no means the same, but resonating a little bit with what Dima said, despite that segregation, Johannesburg is an incredibly vibrant place. There are so many incredible rituals, practices, mythologies, and belief systems that have found intelligences and ways to be in the city despite this infrastructure that is so incredibly segregated. For us, that was really something that was very inspiring, that we wanted to be able to translate into design form and design expression.

So, the practice was born with this interest and with this love. It was not fully articulated at this stage, but we were intuitively interested in our city and we wanted to find languages to express that. My work now spans territories, mostly in Africa, but really, I’m working around the world because, by extension, so many of these territories touch on other territories, and somehow our work has found itself becoming always about the relationship between places and between territories. For example, we are working on a project in Nigeria, on the campus where the Benin Bronzes are being returned by Germany. I’m working on a project in Kenya that is a memorial for African soldiers who lost their lives fighting alongside the British and were never given a dignified burial. Another project in Johannesburg, on the campus of a Pan-African library, is thinking about women storytellers across the continent and its Pan-African solidarities, as well as the relationship to our own city and our own context. Somehow, I’m always finding myself interested in the relations between places and between geographies.

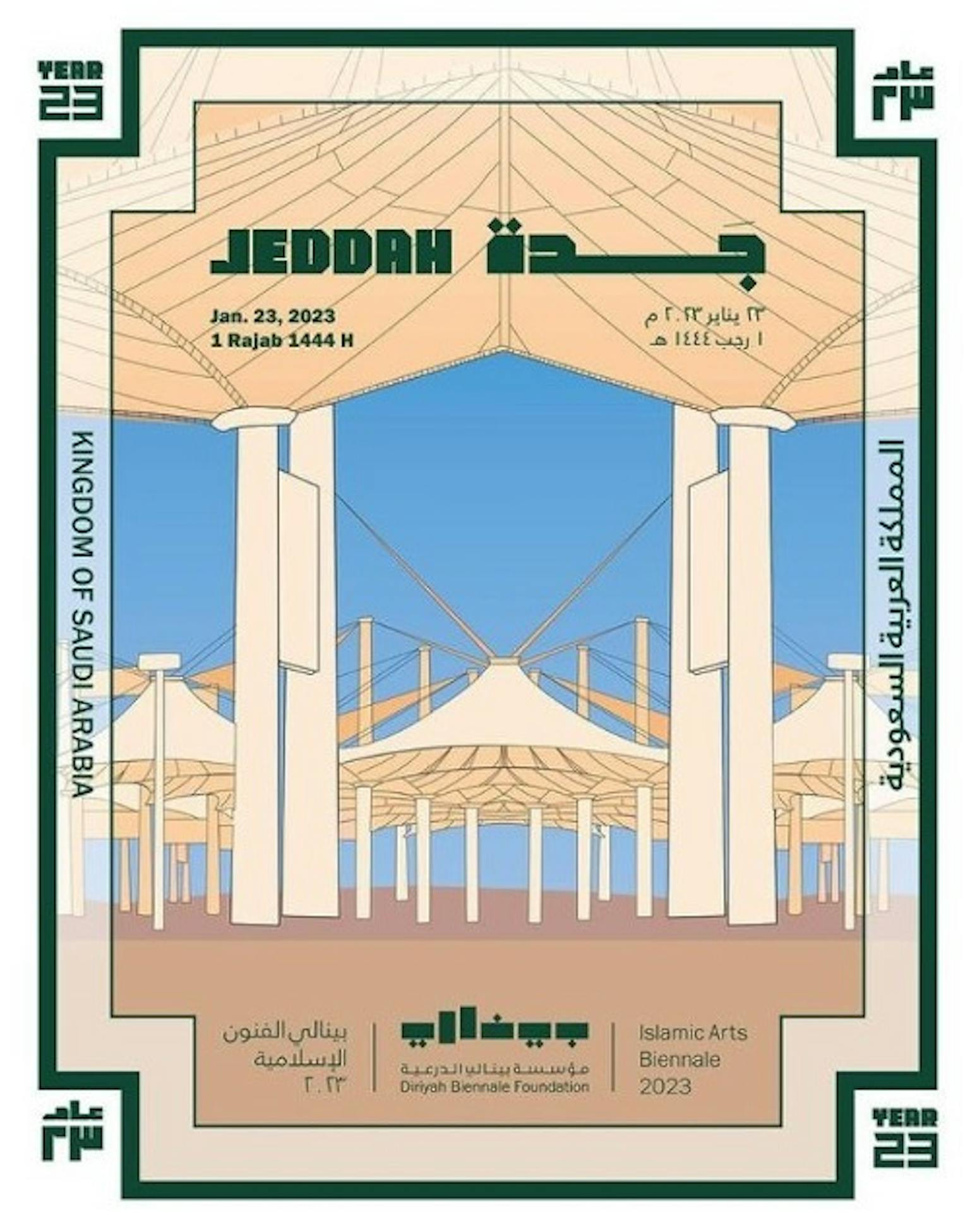

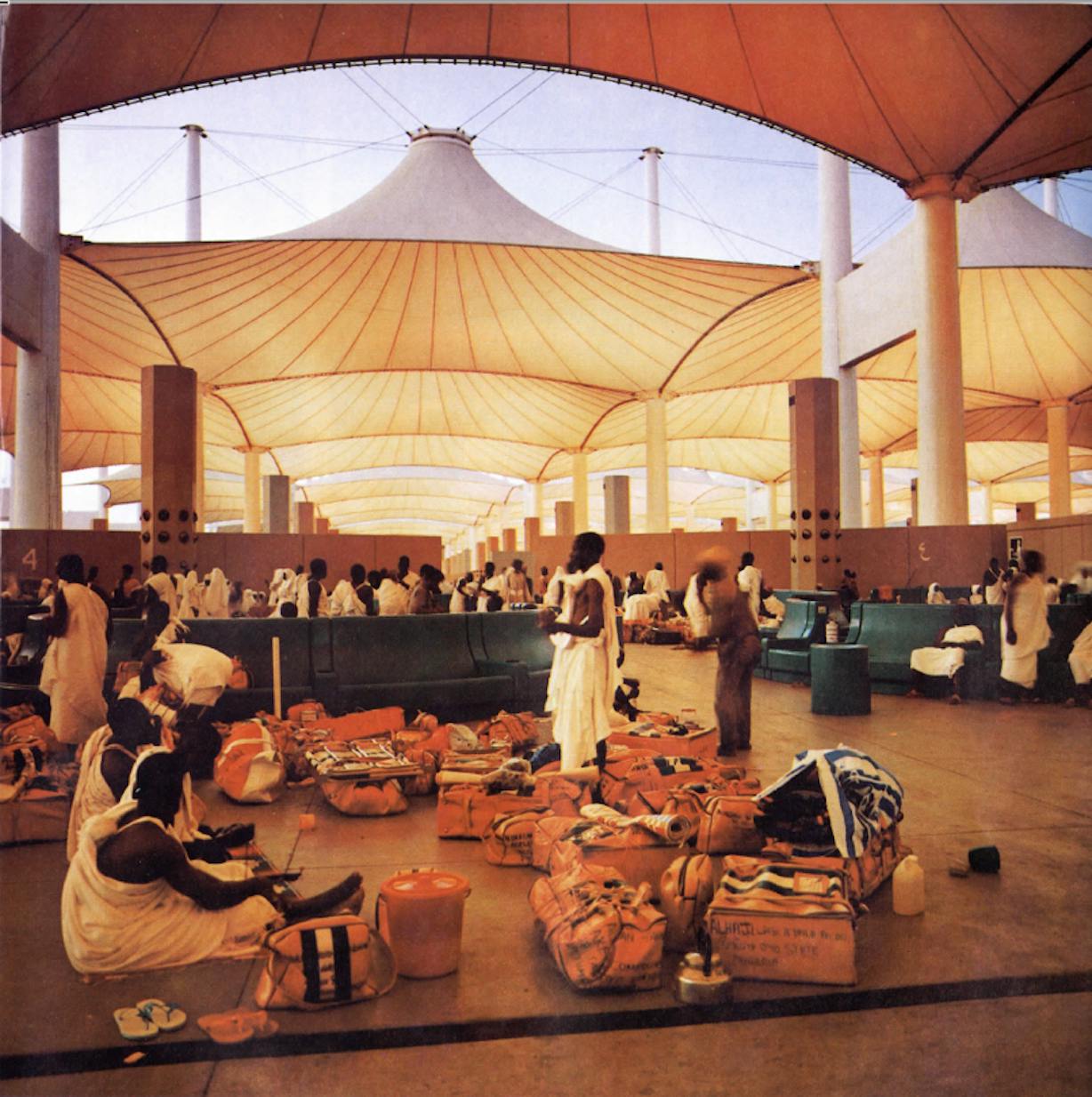

I wanted to start by talking about my experience working on the first Islamic Arts Biennale that took place in Jeddah two years ago. At the time, it was a new project. We were in the process of selecting a site and building a team. As it was the first of its kind, we really had to think about what an Islamic Arts Biennale is. It took place on the site of the Western Hajj Terminal – an unused land parcel of the airport where pilgrims land when they come for Hajj. Working in that context with those lineages and heritages was, for me, something to really think about and work with. This airport terminal is really first and foremost designed as a gathering space. In its configuration, it also resists the idea of an airport as a non-place or a space for commerce. When I first visited the site professionally, I was flooded with memories of being there as a 14-year-old pilgrim; seeing people from around the world, hearing sounds and accents from many places, and really experiencing it as a gathering place for people from many different backgrounds.

These are just some slides of the terminal when it first opened. In conceiving what this biennale was for me, I was very aware that I’m an architect, I’m not an Islamic scholar, and I’m not a curator by profession. I was very aware that I was stepping into a very well-known and well-trodden art-historical canon. That canon has largely been defined from a Eurocentric perspective, beginning in 17th-century France, and is inherently colonial in how it has defined Islamic artworks by viewing them as aesthetic objects, or looking at them through their geography and chronology alone, and not really thinking about the experience or philosophy they embody. That was really my starting point: how do we think from the inside out? How do we use this platform as a space to not just represent who we are, but manifest who we want to be? How do we work with it as a platform to research things without having to explain a baseline? And what do different definitions of Islamic art look like from our perspective?

It was a largely contemporary biennale, but we did work with historic objects that were made by incredible Islamic creatives and scholars. It was important to be able to situate contemporary works within a lineage of historic works and at the same time give these historic works a future by putting them in conversation with contemporary artworks and interpretations.

But what was really powerful for me was that this project didn’t have to work from a place of negating anything. It didn’t have to say: I am not this, I am not this, I am not this. It simply tried to say: this is who we are, and this is how we want to express ourselves through this platform, in this moment, in this time. I think this approach really challenges the general practice of a lot of traditional museums. In Islam, the way that we honour is often through touch, through the senses, and being confronted with these questions in an institutional setting was, for me, something really interesting to be able to work with. How do we actually situate contemporary works alongside institutional legacies that we have inherited but do not question?

Dima Srouji, Maintaining the Sacred (2023), Islamic Arts Biennale, Jeddah, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

The project featured an incredible contribution from Dima [Srouji], who presented research about and reflections on the windows of Al-Aqsa Mosque. Dima worked on reconstructing some of these window fragments in collaboration with stonemasons and glass masons from Palestine. The biennale asked the question of how do we belong? The theme was ‘Awwal Bait’, which means ‘first house’, and that is a term that is given to the Kaaba in Mecca. Through these two experiences, we worked with how we construct belonging, through our rituals and our prayer, but also through community.

My second prompt is that in any given context and in any given building or site, there are always other contexts, and in working on something in the present, we always select the heritages that we bring forth

Recently, I was asked to compete on a project in Vilvoorde in Belgium, and the brief for the project was very ubiquitous: it was to construct a pedestrian bridge that crosses over a body of water. When I first got the brief, I thought I’m not the right architect – I don’t know enough about this town or the Belgian vernacular to be able to design for this place. But I started to read about Vilvoorde and I found that it was named as one of the most diverse Flemish towns. When I started to look into why, I found that it is an industrial hub, and that the height of its industrial activity was before World War I, when Belgium was a colonial superpower and it brought immense labour from the Congo.

I became really interested in that history, and I found that the first person to study in Belgium from the Congo studied in Vilvoorde. His name was Paul Panda Farnana and he was a genius. He was a kind of African Renaissance man. He was schooled in literature, music, and poetry. He studied horticulture in Vilvoorde and passed cum laude, and went on to plant all over Belgium and the Congo. He was then conscripted to the army and, like all people from the Congo at that time, was treated with extreme violence and discrimination. That experience really turned him into an activist, so when he came back from the war, he started to advocate for the wages of Black people to be fairer. He noted down in the record all the comrades that he had lost. He was instrumental in organising the first Pan-African conferences with Du Bois and others in Europe. He made a huge and significant contribution to the lives of Black people in that country, to Pan-African discourse and thought at the time, but has very sadly been erased from history. He was assassinated by poison in his early 40s, and when he died, Belgium officially banned people from the Congo from studying in the country because of the impact that he had. It’s only since the 1980s that people really started to speak more about his legacy and his work. Congolese academics made a documentary that has started to spread knowledge about who he was. He is still quite unknown in Belgium, unfortunately.

So, when we found this story, we decided that our project had to be a homage to him, and this is really the site that we wanted to be able to work with. We started looking at water architectures from Congo and we discovered these incredible boat structures that, when they are stacked up next to each other, become gathering places. We liked the idea of a bridge as a place of gathering. Our bridge is a series of conjoined carved boats, and each of them is going to be planted with species from Farnana’s horticultural research. In addition to this main bridge structure, we are also going to have smaller boat structures that will float along the riverbank and pollinate new ecologies in a landscape where people previously toiled and lost their lives. What’s important about these structures is that they are going to be in collaboration with community schools and institutions, so children will tend to the gardens and learn about the story of Farnana.

When we presented this project to the jury, they said that they had never heard of Farnana, but they were very moved by the story, so they started to publish articles in the local newspapers before they announced that we had won. Farnana has now been included in the Flemish canon and curriculum, which is incredible. Sorry for talking about this so much, but I just wanted to make one more point about it. Belgium had an election last year and the government elected was very, very right wing. The mayor of Vilvoorde also changed, so we are now fundraising for the project, and I don’t know if it will happen, but the people working in the city office are still the same, so I’m hopeful. This image is of a project that we did nearby to raise awareness for the project. I wanted to talk about this idea, like those little boats, of being able to network across structures.

Sumayya Vally, Grains of Paradise (2024), Triennale Brugge, 2024.

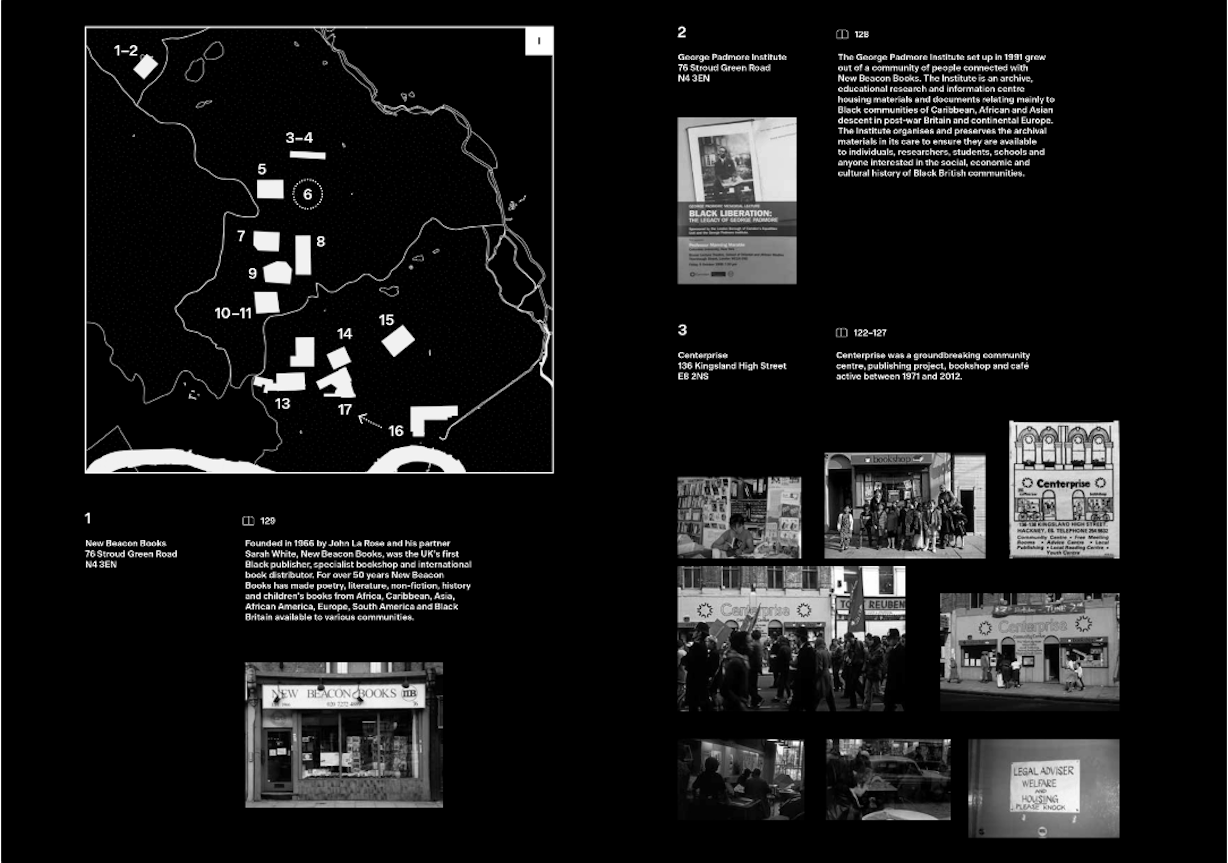

I worked on the Serpentine Pavilion four years ago now in London, and at that time, my practice was really based in Johannesburg. I hadn’t been anywhere else, and I had no ambitions of working anywhere else either. The Serpentine Pavilion is really a platform that is a manifesto for an architect. It’s often an architect showcasing what they can do in terms of how they create expressive forms. Because my practice is so tied to thinking about Johannesburg and how to express Johannesburg, I really started to think about how to express London to London. I started to look at London’s waves of migration, and places of belonging that became important for communities when they first moved to London. We started to look at some of the first mosques, African churches, synagogues, and also marketplaces, where someone could find ingredients for traditional recipes; or cinemas, where someone would be able to hear something in their mother tongue; or places like The Four Aces Club in Dalston, which was one of the first venues to play Black music in London.

We started to map out these spaces and what their gestures of generosity were. How did they create surfaces for people to gather under and over? For example, in a marketplace, there is the awning, but also the counter surface that enables a space of transaction and exchange. The pavilion design brought together these gestures of generosity, if you will, and it became an abstraction of these many different gathering places in London; it became a place to convene and gather. The furniture was kind of embedded within the structure – there was no distinction between wall, floor, roof, furniture. The thing that I really learned from the research was that it was important to honour these places in terms of their architectural form, but there was also so much about what made them cultural institutions that was intangible. I mentioned some of this in the discussion yesterday: the presence of food, the presence of mother tongues, of sounds, of ritual practices that came from other geographies. This is really what made people feel a sense of belonging, or what contributed to that sense of belonging, and I wanted to be able to somehow work with that too.

We started to place fragments of the pavilion in four sites across London that were part of the research, and that became a catalyst for working on programming with New Beacon Books in Finsbury Park; with the Valence Library in Dagenham, where we worked on a radio station drawing on the Serpentine’s education and civic programme; and with the Tabernacle in Notting Hill, where I’m still working with the artist Alvaro Barrington on a project called ‘Sound System Sundays’. Really, this was an opportunity beyond the physical form to extend into London and to put the Serpentine in conversation with community arts institutions and initiate and generate that exchange. That’s something that I think about a lot in my work: how are we thinking about the forms that we express, the aesthetics and the beauty that we express? But also, how are we thinking about networks across spaces? Many of the works that we saw in the Islamic Arts Biennale were produced in different places, with collectives of women, for example. There was also an intention to think about what would happen in this exchange between host and home, which is something that I’m interested in, and I want to think with everyone here how we can express that.

Dima Srouji: Thank you so much, Sumayya and Ibrahim, we could listen to you for hours – the imagery was beautiful as well. I have a lot of questions for both of you about the specifics of your practices and how you centre education and your relationship to communities that you work with. But my first question is about this building. Can you each tell me how you felt walking in for the first time?

Ibrahim Mahama: Certainly. It’s undeniably very beautiful. I really like this space for what it is – just thinking about the architectural details. I remember yesterday, when we were going up to see the other parts of the building, I was more interested in seeing the shape of the building from the rooftop, seeing how simple it is from the outside, but the inside is very intricate and detailed. Certainly, of course, it also reminds us of a certain specific period, but I think it’s quite interesting. One might think that maybe the space, in terms of its architectural composition, doesn’t lend itself to contemporary work – that it somehow might be a bit conflicting – but that’s the point of art and culture: to create those tensions, and it’s literally a beautiful tension.

Sumayya Vally: I felt immediately intimidated when I walked into the building the first time. I don’t know if I consider it a beautiful building necessarily. It’s certainly a grand building and it has a very expressive language, but there’s also a lot about it that is not expressive at all and not coherent by any means. I think there’s a hodgepodge of lots of decisions and details that have happened over time, perhaps without enough thought or intention. Our profession has so much that we just inherit without question and so many of those decisions are expressed in the building. I mean, we’re lucky that we have carpet here and we have panelling that’s hiding some of the details. But there’s not a lot that feels like it was intentional when decisions were made about how it was developed over time.

Dima Srouji: What’s interesting in that, is there are details that are beautiful in terms of the scale – maybe some of the ornaments, the lighting, the way it filters, especially with these skylights. There is a friction there in what we are conditioned to feel because the canon of architecture conditions us over generations to appreciate a particular type of language.

My question for Sumayya is: how can we, and how do you in your own practice, try to disengage from that physically as a designer? As an architect myself and as an architectural educator, it’s very difficult to start from scratch, right? There’s no such thing as an original language, and we are confronted with it spatially in London every day. We are confronted with it through architectural books. If you look for a reference to give to a student, it’s very difficult to find a reference that doesn’t use a western language. So, what are the design decisions that you have shown us today? How do you transition from the language that you presented verbally to the language of form? And what does that process look like to you as a designer?

Sumayya Vally: I don’t know that I’m in search of a pure expression or form that is coming from any one particular place, because I don’t think it exists. I don’t know that it should exist either, because I think our histories, our presents, and our futures are clearly so much about this connection between different places, different territories, and different conditions. I think we are all simultaneous. What we are wearing, how we are sitting; everything is enmeshed with so many different heritages. And how we all are, how we all live, how we all practise our daily lives; it is imbued with resonances, references, and practices from around the world.

Maybe it’s difficult to think about how to get away from or disengage a particular language entirely, but thinking about how we are intentional with what we do with the languages we have is where I feel like I maybe have a little bit of agency. I think that what things look like and how it expresses who we are in the world is certainly important, because we are born into it and it evolves our sense of belonging. That question should be complex, and it should be challenging, because to see something as essential is also problematic in a way.

Dima Srouji: So, you are embracing the complexity of that history. Ibrahim, you showed us a few images of the centres that you are engaging with, and one of the moments that really stuck with me was when you were laughing about the question of audience, because the relationship to objects, to spaces, doesn’t necessarily need to have an audience. As you noted, they kind of exist within themselves as entities that have embedded memories, as this building does. Could you talk us through this idea a little bit more? I’d love to hear more about your relationship to inanimate form as an artist, but also as a builder of institutions.

Ibrahim Mahama: I think it’s quite interesting, because for me, when I’m travelling through the city, when I’m home, and when I’m going to places and I see something, the form or the aesthetics is the first thing that attracts my attention. Then certainly you want to find out more about the history of it, what it can do. I am fond of collecting objects – many different types of objects – but I collect because I think of these objects as archives.

There is this project that I’m currently working on at home, which is a building that was built in 1966. Specifically, it opened on 5 February 1966, and a few days later, Nkrumah travelled to Vietnam and then he was overthrown as president of Ghana. So it was the last industrial project that he worked on. Much later on, the building functioned for a few years as the sole factory that produced all the glass materials that were used in Ghana – it was the largest glass factory in West Africa. It produced all the Coke bottles; all the Fanta, Sprite, Guinness bottles, everything. It even produced all the level plates that were used in architecture.

At some point, the factory was abandoned. In the last couple of months, we had an election, and when the previous government was leaving office, they sold off a couple of government spaces, and this factory was one of them. It was sold to a company that was meant to cut the entire factory to pieces, so I had to negotiate with this company to buy parts of the building as an archive. I had to go in there to collect all the company records, to collect all the moulds that were used in the making of the glass, but also to collect all the glass that was made but never sold. There were like 300,000 pieces of glass that were sitting in the building that needed to be rescued. There were also millions of tonnes of broken glass that were rejected because they were not of good enough condition to be sold.

I’m also very much interested in the failures of these forms and these objects. I think we are trying to find some kind of redemption by taking these objects and parts of the building. When I bought part of the building, someone asked: ‘But what would you do with this building?’ And I said we can reconstitute it; we can rebuild it in such a way that it doesn’t necessarily have to be a glass factory anymore, such that it proposes new ways of interacting or dealing with those histories. Because you can imagine, in 1960, Ghana was mediating peace in Vietnam and other places. We were sending engineers to Singapore and Malaysia, and today we can’t even produce toothpicks, so there is a lot of history and knowledge embedded within that space.

That’s why I started with the silo, because I thought that it’s so ridiculous – there’s an element of stupidity in this. Why would you do such a thing? Art is already precarious enough. As an artist, you struggle to produce these types of works. Very few institutions can acquire the kind of work that we propose. Why risk the capital that is generated out of that process in order to go back and confront these failures? That’s what these objects represent. I like the senselessness and stupidity within this idea. It’s so silly. Like, why would you even do something like that? It doesn’t make any sense, but at the same time, it makes perfect sense because you are opening up a very different paradigm for many different generations. Because there are people who exist and they know about these histories, but they never really thought about it because they thought it was just the way we experience time – something happened and then it stopped. Then you come in and say, no, actually it hasn’t stopped, it was only paused. Now we can reconstitute it, and we can go back further in time and then rethink it.

Dima Srouji: It got me thinking a lot about the concept of repair, and how in all of our practices – and I think also what we are trying to do here – we are kind of restitching communities back together, especially one in London that’s incredibly fragmented. The relationship to repair in both of your practices, I think, is very strong, especially in the relationship of the part to the whole – which could be a mound of glass rubble that you’re bringing back and reconfiguring in a new form. So it’s an act of physical repair in some ways, but then there’s also a psychic repair that I’m interested in thinking through with you. What is your relationship to psychic repair in relation to your physical practices? Do you feel like the physical output of architecture can bring about that healing on a collective level? Do you believe in that, and why?

Sumayya Vally: I hope it doesn’t sound too big, but I’ve always said that in Johannesburg you can see and feel on an architectural and urban level how much design was involved in keeping people apart. On an infrastructural level, the way that our city was segregated and where people lived was entirely by design, according to where they sat on the colour line, or where they were determined to sit. It was designed. So in buffer zones around white neighbourhoods there were zoos, parks, and trees, and the further you go on the racial spectrum the more toxic those environments were. So around Black communities people live next to radioactive waste. The community that I grew up in and is still my home is next to an industrial factory area with toxic fumes that are dumped into our water system. That was an act of very meticulous design, on an infrastructural and architectural level. All of the services that we grew up with – hospitals, schools, and so on – were all designed to tell you where you fit into society and the kind of dignity that you deserve from that ethos and from that ideology.

If we understand that architecture can be a force for keeping us apart and enforcing those hierarchies, then we have to understand that it can also be a force for the opposite. I think the constitution and design of physical structures can be so that it brings us together. That is something that I’m aiming to do in my work.

This is relevant even in how we constitute institutions. I was thinking about this when I worked on the biennale, because so many people said that the project was exclusive and questioned why something would be titled an Islamic Arts Biennale. But you know, my parents came to the project and, for the first time, I felt that the pilgrims were landing across the road, and because it was called an Islamic Arts Biennale, it became a place where people felt like they could belong without the intimidation that perhaps they might feel in relation to a contemporary art museum – like my parents, who would come and see some of my other work but perhaps not necessarily feel like it has anything to do with them. I think the way we construct platforms implicitly expresses an ideology in who it speaks to and how it brings people together.

Dima Srouji: There’s a relationship to belonging here that’s really important. We have about 20 minutes left – I think we can open it up to questions from the audience.

Muhannad Hariri: Thank you so much. That was really enlightening and interesting. I just wanted to go back to that discussion that the two of you had about language purity, being able to kind of excavate a pure language. And I totally agree, you have to embrace the complexity. But I just wanted to point out an interesting connection. Stupidity, idiocy – I’m very attracted to stupidity and idiocy because they’re not thoughtlessness. To be an idiot, or to be idiomatic, to be someone who doesn’t speak a language that others speak, can include a lot of thoughtfulness. Shumon pointed out what I described – what I was doing on Instagram – as idiotic. I’m just posting text on an image-based app, but it was the right kind of idiocy for me to find an authentic way to express myself and develop an emotional connection with a lot of people, because I didn’t follow a basic rule. I just kind of went with that. There’s a lot to be said about entering a space, or entering a discourse, or entering a historical tradition and not misusing but maybe listening to what seems outdated or less fashionable, or to someone that thinks that they’re irrelevant. They often have a lot of concealed wisdom, to get back to that first point, that gives you an authentic language, a new affect, or a new relationship.

Shumon Basar: Actually, I wanted to ask you, Ibrahim – because I think these first impressions are valuable – I’m curious about your first impression walking into this building, wandering around, seeing it. What would you do to it? How much would you keep? How much would you change? And I want to put that to everyone really. Because I think when we’ve been having conversations, I always talk about sliding scales, from maximum to minimum, and it’s very obvious here. Like what would be a maximum version of trying to efface, suppress, alter the language: somebody could turn it into a pure white cube, almost ghostly, and you send everything away, as it were. Or we’re in a kind of Richard Curtis film, and you fetishise the historical grammar, etc. To me, those are the two extremes, both of which I think should be absolutely rejected, which means we’re always somewhere in the middle. But then there’s also an infinite number of ways of being in the middle. I’d love to push our guests, because we only get first impressions once, to get a sense of that. Ibrahim, perhaps you could be the first to respond. How much do we celebrate, how much do we question?

Ibrahim Mahama: Certainly, I’m not a purist. I like to embrace things for how they are. Sometimes I wouldn’t like to change much within the thing; I just want to be able to confront it through various installations or things like that. One of the key decisions that I had to make when I was constituting this parliamentary form in the project that I did at home, was to think about the question of this historical labour and how that could be represented within the architecture.

Predominantly in West Africa, they have these paper bags from cement that they fold into hats for construction. I thought that was a very important form in terms of what it represents in terms of labour, because each time it’s made into a hat, it means that someone is going to carry about 500 kilos of weight a day in a construction site. I thought by calculating that over a decade, it’s almost the weight of the entire building, so I had to take that as a way to make an intervention within the building. So sometimes they are just very little interventions, they’re very symbolic. But in just doing very little interventions, there is a certain kind of subtle confrontation that happens within the space. There are people today in Ghana who like to build spaces like this because they’re like: ‘Oh yes, that new building, we want it to look like this building we saw in London.’ They’re not really interested in the historicity of the space and things like that, but I always find it very interesting when I see such spaces. Sometimes I want to be in the space, and I just want to be able to celebrate this space for what it is, whether for its criticality or mediocrity or whatever it is.

Oscar Guardiola-Rivera: Thanks very much. I just want to hear more from Sumayya on this idea that infrastructure and architecture design our senses of belonging; they frame the way we are, and they teach us where we should be placed. Also, in relation to that, Ibrahim, could you tell us more about what idea of a parliament you have in mind when you’re building these parliament-like installations?

Sumayya Vally: I think you framed that much more articulately than I did, but that is what I was trying to say. It operates on a very deep level because architecture is something that we are all born into and that subconsciously we all know about. I think people maybe can feel more distanced from other art forms, but architecture is something that everybody knows and has an experience of. On that level, it is so deeply ingrained and it’s so subliminal, and it is so dangerous and so powerful – I genuinely believe that’s why I’m an architect. I don’t have more to extend on that, but just to agree on that point about how powerful it is. I really think it is a tool for being able to bring people together – to express cultural edifices, and forms of expression, and forms of beauty, and mythologies and belief systems, and ways of gathering that we want to aspire towards. I think it can do all those things. Then it will just seep into our psychology slowly and become a part of who we are and change the world.

Ibrahim Mahama: Thank you. I don’t necessarily think I’m building the parliament for people. I’m more or less building the parliament for the sake of the process of building it, because there are many things that you confront in the architectural process. For instance, you are building a space, and then you realise that there are many places in the world where there are a lot of buildings that were once started but completely abandoned, and you find that kids go there over a long period to play. There are many of those in Ghana and I’ve always asked myself, why is it that when spaces are under construction, sometimes that’s the most interesting aspect of those spaces?

Because as an artist, no one ever said that you have to create an artwork to be presented within a white cube. I work with a white cube gallery, so when I’m making work and thinking about my relationship to the white cube through my own art-historical training, I’m also thinking: what about these other forms of spaces? Because there are a lot of people who are coming from marginal spaces. In the Global South, even when it comes to this idea of institution building, there are not so many institutions – that is, public institutions (and by public I don’t mean governmental) and even private institutions – that are built in spaces that are open to people ordinarily.

Thinking that you can make a work that can exist in any context is very important for me. That’s why when I was building the parliament, I was more interested in the process of it, because you can build something and invite people to make interventions within that building process. I don’t see the difference between that and using an old, abandoned space or a space that we’re rescuing, or whatever. I think it’s a political position that sometimes creatives have to take, and that, for me, is what the Parliament of Ghosts is. The ghosts are all the potentialities that are represented within the process of trying to develop this system.

Taghrid Choucair-Vizoso: I guess in response to your question, I’d like to enter it from the point of: what can we do to repair? What’s the functionality of this building? How can it become resilient to climate catastrophe? Taking this as a point of departure, I don’t know if we need to add more, produce more, or break it down and rebuild it. What can we do from a fundamentally functional level? London will suffer from floods in the very near future. We have already suffered from floods. What will we do to mitigate and adapt? People in London seek refuge during heatwaves; how can we be pragmatic with the architecture to ensure that it’s well-insulated for both extreme heat and extreme cold at the same time? People also seek refuge in arts buildings when it’s too cold. These are questions we all have to face. We’re already too late. But it’s very possible to return to thinking about what materials we are using and find out where they have come from. How can we use this building as an opportunity to practise a circular economy? And how can that be a living example for other buildings in London? I enter it from that very fundamental space that then takes us to: how can we create more oxygen across the cultural sector?

Dima Srouji: If anyone also has any ideas of what to do with the building, speak up now. If you want to share how you felt walking in as well, that would be really nice to hear.

Adam Broomberg: Thank you. That was beautiful. I think I’m one of the few people who is lucky enough for this to be the second impression. I came and saw the building about six weeks ago, and I walked through the door with you today, and I was like, oh my God. And I said, ‘what have you done?’ And you said, ‘isn’t it amazing?’ And I’m sorry to keep going on about the carpets, but I’m going to do it because my impression is so different walking in this time compared to the first time. And I think it’s really essential to point out how the small changes – like the white carpet, the stage, the fact that there are two olive trees being used as decoration on either side of it that are not rooted – are huge changes. They communicate a lot about the institution already. The two of us were discussing how we felt this morning – how much we had to digest. Listening to these magnificent voices all day yesterday and this morning – it’s already a lot to take in when we’re trying to think. Is there the space to think after that? You know, I feel totally saturated. I guess what I’m saying is how each tiny little decision communicates so much, and already so much has been communicated just through these seemingly tiny gestures.

Taous Dahmani: Thank you so much. I guess, like Adam, I had the chance to see it before and had a very different feeling. I’ve been thinking since yesterday about what do we need to think and what do we need to feel? And about how those two questions are related and how they can sort of help each other in order to think about complex ideas; in order to think about what this space could be. I need to be comfortable – I don’t know about you guys – to even think about uncomfortable things. To go back to the conversation last night, we talked about people who don’t have homes and about how Ibraaz can become a home in the most obvious ways. Hospitality as a radical way of thinking about Ibraaz as a sort of embassy – thinking about houses and homes and the ways in which an institution can be a comfortable space to think about uncomfortable things.

David Velasco: I still feel the pleasure of the space – the light, the scale – and I’m also very curious about the history of it, which we haven’t really talked so much about. It was the German Athenaeum, and it is a neoclassical building formed in this period, but I would be curious, as you’re considering how you might change it, how that figures into it? My instinct is also that it would be really interesting to see how artists each take that on, rather than having an architectural intervention that creates a new surface for them.

Sumayya Vally: The history of the building is really interesting and as I mentioned, working with different layers of history becomes a site to work with, for sure, or sites to work with. But the other thing, and I mentioned this to Lina when I first walked into the building, is that I’m interested in working like an architect that also works like a curator. So, when I worked with the Serpentine Pavilion, I thought about these other community institutions and how we can work with them – to bring them into the conversation – and how we can have different artists activate some of those places. The same for the bridge project, which has a network of places it’s working with and horticulturalists we are collaborating with.

Something that I’m really interested in doing is to not only work as an architect, but also as a curator to initiate commissions, potentially, in some of the spaces with other artists. We’ve already started doing research towards this. Of course, we have budget constraints to think about, but I’m certainly not imagining this as the overarching voice of one person. I think it needs to be very much about how we bring in other voices, through programming, physical interventions, and in the experience created. Of course, it needs to be curated so that someone is thinking about how everything fits together. But we are thinking about a kind of background design language and how different things are activated through working with different voices. The other thing I wanted to add, is that it’s important to think about how this broader network of places are physically represented, but also how we start to communicate across London and beyond.

Evan Ifekoya: Thank you for these insights. In response to the question around changes and impressions: actually, the first thing I noticed and felt discomfort around is the lighting. Because there are a lot of really beautiful windows that allow a lot of natural light. Yet the lighting in the space is very warm, so it kind of works against that natural light in the space. A question that I had is around the lighting, especially in the upstairs spaces, if they’re going to be used as gallery spaces: how are they going to work with, or for, or perhaps against, in tension with, the works that are on display? Because right now we kind of have a single tone that carries through the building, and it does a lot to how one feels in a space. Speaking to the idea that came up around the intangible, lighting does a lot.

Nadja Argyropoulou: Thank you very much. For me, this was very close to home. The Ibraaz building in London is beautiful but looks and feels too much like a Parthenon-type enclosure: the design, the colours, and the architecture of an ideal, of the imaginary of balance. Everything is maybe too framed and framing – the columns, the olive trees. So, I guess my thought was how can you unsettle, rewild this type of framing? If you think about it, even the Parthenon columns were crooked, slightly curved, uneven. There is an interesting challenge there.

Sam Samiee: What I thought when I entered – taking on what Françoise [Vergés] said yesterday and continuing Adam’s point on the very little details that influence this space – was how delicious it is to imagine that each artist was going to come into this building and change it so dramatically and differently from another artist. It would be beyond my imagination what they would do and I want to maintain that. Instead of thinking that what we think today is the priority, I would avoid any patronising imagination or planning that would impose on future artists who want to intervene in this space. I take this very much from conversations with the concierges and the production teams of institutions in Europe. They’re always like, ‘The artist comes into the building and does whatever he or she wants with the building.’ I think that’s something we want as an art institute: for every artist who comes in to be given that space and clear slate.

farid rakun (ruangrupa), Ibrahim Mahama, Jaya Klara Brekke

Ibrahim Mahama

Ibrahim Mahama & Shumon Basar