- Mission Statement

5. The Building

Ibrahim Mahama, Sumayya Vally

Mission Statement 00: Why Now?

This is a lightly edited transcript of the fourth session of Ibraaz Mission Gathering 00: Why Now? which took place on 21–22 February 2025.

Panellists: Muhannad Hariri, Al Hassan Elwan, Günseli Yalcinkaya

Moderator: Shumon Basar

Respondents: Hannah Cobb, Declan Colquitt, Zein Majali, Malak Helmy, Jaya Klara Brekke, Nesrine Malik, Mona Chalabi

Shumon Basar: I’m so happy to have, honestly, three of my favourite online avatars on stage. We have Al Hassan, aka @postp0stpost or POSTPOSTPOST™, Muhannad Hariri, and Günseli Yalcinkaya. I will give a brief introduction, then we are going to go through some thoughts from each of our guests. You are all familiar with the format so far, so here we go.

Memes are the crystallisation of how words and images synthesise into a new language. ‘With memes, images are converging more on the linguistic, becoming flattened into something more like symbols, hieroglyphics, hieroglyphs, words,’ claims writer Olivia Kan-Sperling. I would argue that those inducted into this form of literacy read words as images and images as words. As Kan-Sperling writes: ‘A meme is lower resolution in terms of its aesthetic affordances than a normal picture, because you barely have to look at it to know what it’s doing.’ And the last part of her quote reads: ‘For the literate, its full meaning unfolds at a glance’.1 Its full meaning unfolds at a glance.

Feed now.

So, the feed is made of posts, which are vertical; Stories, horizontal; Reels or TikTok, which run along both axes. The feed is axial. Am I in the feed or is the feed inside me? The feed is a place and a non-place. It’s a record of time and it’s the antithesis of time and un-time, where words and images and adverts and recommendations and distorted inflections of who you are all combine into this viscous digital slime that attacks your attention and replaces it with distraction. I don’t know where the feed ends and where I begin. Suddenly it’s 3:34 a.m. and the birds are singing.

The axis of posting. During this fraught period, I noticed a number of Instagram accounts that dedicate themselves to posting about what’s been happening. They’ve made posting a daily artistic, ethical, and intellectual practice. This practice of posting produces parallel, often interconnected, often contradictory commentaries that are partly acts of witnessing, amplifying, writing, contextualising, decontextualising, and most of all, feeling the daily will to post. This practice is a coping mechanism performed in the corporate playground of platform publics. We post despite knowing that posting may be impotent, but we are compelled to post because we know that not to post is maybe more impotent and a sign of being defeated, a defeat of will, and a win for our enemies.

This loose group of accounts, mostly based in the MENA area or deriving from authors that have some kind of familial, sentimental, or biographical tie to the region, became known as ‘the axis of posting’. This was a term coined by the Instagram user ‘Stibbons’. It’s a wry homage to the ‘axis of evil’, a term made infamous after George W. Bush’s 2002 State of the Union address in the lead up to US invasion of Iraq in 2003. In my humble opinion, the content produced, reproduced, shared, and subtitled by the social media axis is some of the most incisive and relevant cultural material of our times. To go back to a sense of disconnect that I often feel in most galleries and museums these days – their ineffectual mannerisms only point towards the impotent introversions of the art world. The axis of posting and those adjacent to it are making what could only be made today with our 2020s tools and technologies and need to constantly take screenshots. So very many screenshots. Are there more screenshots than there are stars in the sky?

So, this conversation is about when to be online, when to be offline, and when to do both, and what might it possibly mean to do both at the same time? At this point, I would like to invite my first guest, Muhannad Hariri. Muhannad may not be familiar to you in his corporeal form, but those of you who have been in the feed, in the axis of posting, I believe will be very familiar with Muhannad’s output over the last 16 months, which we are now going to invite Muhannad to present.

Muhannad Hariri: If two years ago you had asked me, ‘you’re going to be in this get together, which panel will you be on?’, I would have never thought it would be ‘Online/Offline’. I didn’t even have Instagram then. I didn’t do anything online. I’m an academic, not an artist. I’ve been finishing my PhD for 10 years now in philosophy, and it’s almost done. And, you know, my advisor probably wouldn’t have liked how much I was posting, but it got me here, so it couldn’t have been such a bad way to spend my time. That said, I live in Beirut, and the reason why I started posting maniacally from 8 October was because it became a way to cope. If you were in Beirut, from October 2023 until September 2024, you were just waiting for the war to move into our neck of the woods. We were like, this is the future for us; the war will come here. So, posting, was a way to kind of not go crazy with anxiety, a way to deal with the tensions inside Lebanon and inside ourselves. So that’s where that came from.

I will talk a little bit about how my account got deleted around June 2024 – actually, the day before my birthday, which was a funny thing. But it was actually a very traumatising experience because I realised how addicted to posting I was, as a way of coping with things. And I had made so many friends – Shumon’s one of them – that I suddenly just didn’t have anymore. And I also lost everything. Some really wonderful person called Tina had downloaded everything that I had posted and sent it to me, which was cool but also disconcerting.

Shumon Basar: A nice stalker.

Muhannad Hariri: Yeah, it was. It was good. The reason why my name is not my handle is that it used to be Muhannad, my name. Now it’s ‘dan.an.hum’, which is just Muhannad backwards, because I thought I was going to get my old account back but I never got it back, and now I just have a backwards name and everyone’s like, ‘Why is your name Dan?’ Anyway, I’ve been writing a lot: political philosophical reflections, a lot of different things. I’m going to talk about one specific thing that I’ve been writing about, which is actually the thing that I think generated the most interest and actually built a lot of community for me with people who I didn’t know. I wrote this this morning, so I’m just going to read a little bit about the mindset that brought me into this specific kind of writing that I was doing, which I’ll say more about in a second.

When Israel began its onslaught on Gaza, I was like millions of people around the world: overwhelmed by the flood of imagery. Consequently, I felt compelled to reshare, repost, and disseminate everything I saw on social media. Looking back to those early days, I see that it was a compulsive need to be afflicted by the images before inflicting them on others. There was also the algorithm that we had to fight back against to keep Gaza current and at the forefront of all our minds. Somehow, we all knew that this time it would be different – 7 October made us all prophetic. We simply knew that something had changed and that the Israeli reaction would be different this time. Not in kind – it has always been genocidal – but infinitely increased in degree.

Truly, what followed was a gradual yet incessant raising of the volume of violence and outrage. Looking back now, did we all not see it coming? And so, no one was surprised by the flood of violence, though it shocked us every minute of every day; nor, by implication, were we surprised by the flood of imagery on our devices, though it shattered us irrevocably, and we began to live through it all like disoriented fish caught in the deluge. I honestly looked at too many pictures. All of us did. Just way too many. I didn’t know how to. It was this thing of like: we must just keep it current, you have to keep showing them to everyone, you have to keep the algorithm from deleting Gaza. At the same time, I realised that I’m looking, but I’m not really looking. I’m not registering the trauma that actually I was experiencing by looking at all these images.

Part of what I was doing online was starting to write descriptions of the pictures; very gory, detailed. I did that because I didn’t want to just turn this into a kind of new currency for virtue signalling online – like, ‘Oh, look at me, I’m sharing all this stuff because no one’s looking at it anymore’ – and I felt compelled to look excruciatingly closely. Actually, something Eyal [Weizman] said this morning rang a bell for me: ‘Why are you doing this? To what end? What good is going to come of it?’ Well, someone has to do it.

So, the first text, this is not the first one I wrote, but the first one I’ll share with you. It’s from 10 January 2024: They all start with ‘Today I watched’ or ‘Today I saw’. Some people messaged me asking, ‘How are you writing all this stuff from Gaza?’, to which I responded, ‘I’m not in Gaza, I’m in Beirut’. I had to clarify that to some people. They thought I was reporting live, but I was seeing it on the stream, so to speak.

Today I watched a boy, about ten years old, picking up pieces of someone’s brain on the side of the road. His face was expressionless, and he had a purple latex glove. On one hand, he was moving chunks of brain onto a napkin on the ground beside him. All the while, he was looking around blankly at the crowd of people, dragging survivors out from under the rubble of a recent strike. From his face and posture, you’d think he was arranging fruit at a stand.

The next one; I’ll comment on them once I read them, but I’ll just let them make their impression on you.

Today I saw a baby not only dead, but whose skull was so smashed that her head was entirely distended. Somehow, the skin on her head still held the pieces of her skull together, stretching like a water balloon. The brain had liquefied, and you could almost see the shards of her skull swim about inside. What monstrous weapon caused this poor child’s skull to shatter and for her brain to spill inside her head? In what universe is this atrocious crime possible? How is this barbarity permissible?

I just want to mention something here. At some point, whenever some awful imagery would appear – Mosab Abu Toha would be posting something or someone would get the freshest pictures – my DMs would just fill with requests, like, ‘We don’t want to look at it. Can you describe it?’, which I found really weird and troubling. But at the same time, I realised people were like me. They weren’t really looking anymore, right? They weren’t really looking anymore. They weren’t seeing exactly what kind of violence was happening. Just gore, gore, gore, you know? So, these descriptions, at some level, gave people a framework. Some of them turned a bit more literary, and I always tried to not overdo that because that would be cheesy and inappropriate. Here’s another one:

Today I saw a young man standing in a wide expanse of dirt and blasted rubble. He was looking frantically from side to side, as though unsure which way to go. As though he did not want to go, or even to be, anywhere at all. And while he turned and turned, he kept hoisting a large, bulky green sack over his shoulder, hoisting it over and over again. Every time it slipped back down, the sack was terribly heavy, heavy with the weight of his younger brother, who was inside it, the weight of his dead brother bundled away in a filthy womb of a sack on his brother’s back, the weight of nature in reverse and horror manifest.

This image – I’m sure some of you remember the video – why did I describe it this way? One thing that I always wanted to make sure wasn’t happening was that I wasn’t, let’s say, upstaging the horror with my writing, but giving people a way to actually grasp the horror of what they’re seeing because it’s so easy for us to just say ‘horror, horror, horror’, you know, and continue to scroll, scroll, scroll. The way that Instagram works is that the next picture you might see is a kitten or someone’s ass, and then you are back and you are looking at the gore again. How do you keep the image sacred in that sense?

‘Today I saw the flattened remnants of a young man’ – this was incorrect, I later found out it was an old man:

Today I saw the flattened remnants of a man. All that remained was his youthful arm, its wrist bearing a black zip tie, a signature of having been held in zip ties in captivity. The body itself was pressed with such immense force that its blood and viscera, its organs and its tissues, formed into bubbles, where once whole flesh and bone took form, life was literally squeezed out of him with the track wheels of a tank. The imprint of which can still be seen in the emulsified remains of the boy. A signature of the vile perpetrator, as if one was needed, to go with a zip tie around the wrist.

The next one is the only one from my new account. The other ones I had because Tina sent them to me. I’ll read this one next:

Today I saw a 14-year-old boy lying on a stretcher in the road. He was decapitated and all that remained of his head was a bib of gore and blood that dribbled onto his chest from his open neck. This genocide taught me that when a body is decapitated by the force of an explosion, the cut is never clean, never a mere matter of simply dividing body and head. Instead, the head seems always to be blown off with the pressure of the viscera and tissue that come pouring through the neck. The process is volcanic. Can you imagine so much pressure that your head pops off like a champagne cork, allowing your insides to pour out onto your skin? These weapons are satanic.

At some point, well, 7 May, I wrote this manifesto – I had it pinned at the top of my Instagram profile for quite a while. I’ll just go through this, as maybe it will clarify any questions you have about why I was doing this and why it was meaningful for people.

Why do I look so closely at the images? Because the images are not generic. They depict human beings and each one is absolutely unique. They are all specific and individual. This death and this pain. Why do I describe them? Because vision betrays the unique and the individual, casting it into moulds and general patterns. To write the image in words is not only to force seeing, but it is to inscribe a record.

And that was really important to me. I used to go to sleep thinking, I wish I had a whole army of people like me, so every image that came out of Gaza could be written down; because the images, no one can see them all, and I wanted there to be that record.

What is the record of? The unbearable end of a human life that snaps shut on one end of the camera and strikes me like an arrow in the heart on the other end. I am capturing this relationship I have developed with the dead I have been looking at.

It became really important for me to honour every picture that I saw, and to give each one as much as I possibly humanly could. I think I wrote about 150 or 160 of them, which is very little comparatively. But to me, it was almost like a prayer. It was almost like a way to sit down and not be dehumanised by the images, and also not let the stream dehumanise every single person in what really became just a kind of gore pornography – or ‘gornography’ – because that’s what it turned into. And I found that I wanted to, you know, do that.

Shumon Basar: One of the many things that stood out to me when many of us came across what you were doing at the time, but perhaps the most superficial – and I don’t mean that in a derogatory sense – is that you were using Instagram, which is an app that was founded as a photo sharing platform, to then in a sense ‘détourn’ that to privilege text over image.

These are texts that are about images. Declan [Colquitt] mentioned yesterday to me that there’s the feature where you can get the AI in Instagram to write the text description of the image. So, in a sense, you’re almost doing the human version of that, the image-to-text captioning. But the fact that you were so dogged about never showing an image – your account was just text – is kind of amazing. We have all been thinking about images a lot, and I remember at some point I wrote this:

At some point in the last decade, I think images stopped working as images used to. I know what an image looks like today. I know how they circulate, how they’re currency and fuel, palliative for sore eyes. But no single image can stop the river of the feed, drain it of its compulsion towards procession. Images promise us that they’re still images, but images have become lasting alibis in our anorexic ruins.

That’s why I did want to start with this idea of the feed as something that has velocity. I mean, the feed used to end, no? Like early Twitter, early Instagram, you would get to the end of your feed. The transition to infinite feed and therefore infinite content is again an extremely significant paradigm shift. But the idea, as you say, either in your Stories which are horizontal, or in your feed, you’re like spending a tenth of a second, maybe just like, flick, flick, flick, flick, and you go, you know: atrocity; friend on a Greek island; advert for new dental veneers. It’s like the most demented kind of iconoclasticism in which those images of atrocity, as you say, of which every single one should be honoured, are profoundly dishonoured because of their participation in the incessant flow.

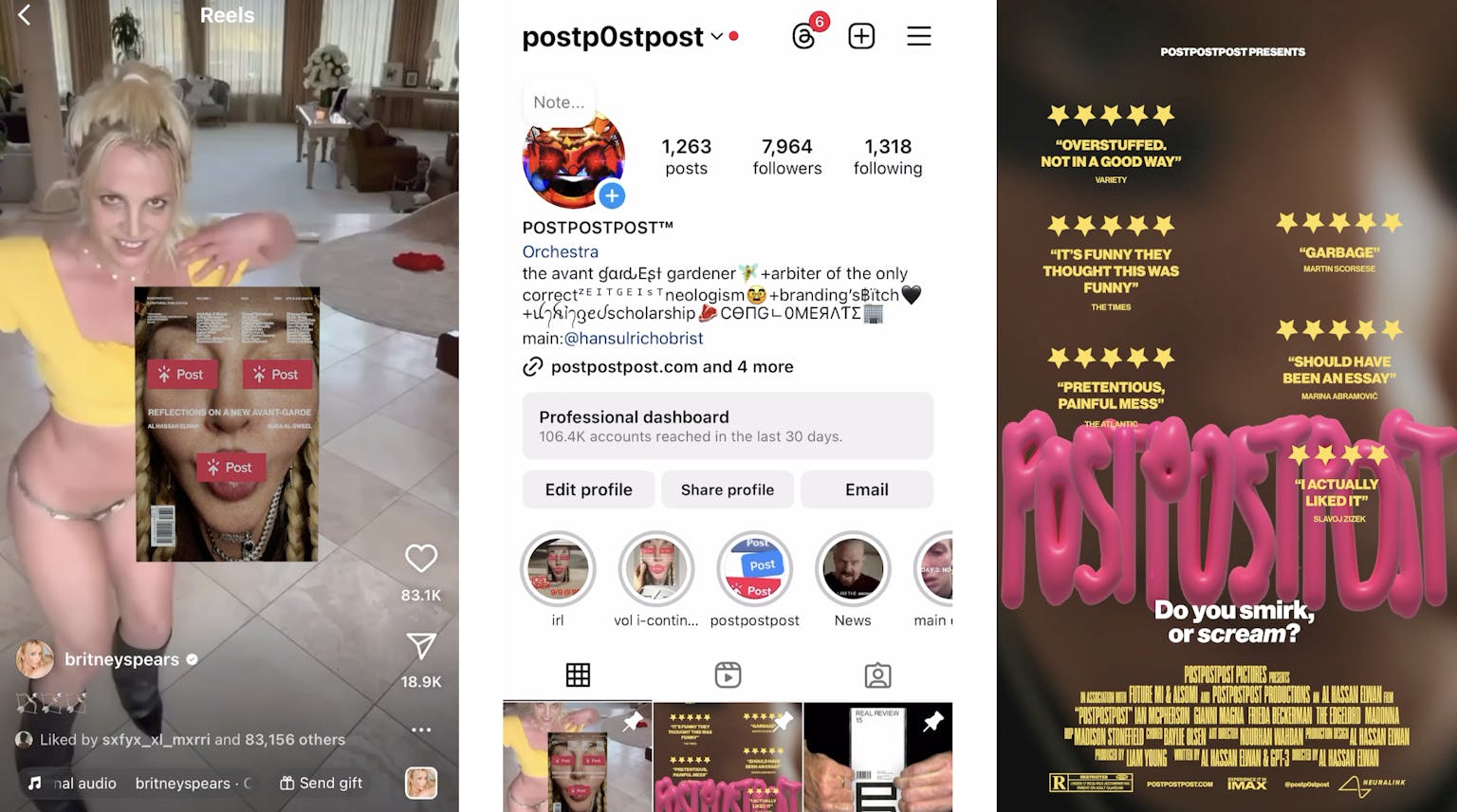

Maybe we can come back to that. But I think it’s worth mentioning, because a lot is, understandably, said about how we are captured by platform capitalism and so on and so forth. But I would still argue there are ways, and I think what you did was find a way that I had never seen, of misusing, let’s say, or using in a different way, the platform to produce a different kind of effect, and that’s something super interesting. And on that point, I’d like to introduce Al Hassan Elwan, aka @postp0stpost. One of the ‘o’s is a zero because, tell us why?

Al Hassan Elwan: Because Hans Ulrich Obrist has the handle for postpostpost with an ‘o’. I DM’d him over 10 times. He’s not getting back to me.

Shumon Basar: We’ll see if we can make that happen today, Al. So just as a way of framing and introducing Al, and his practice of posting, I would argue, prior to 7 October, @postp0stpost was primarily a kind of theory shitposting account. Then after 7 October, it turned into a kind of axis of posting that also became a kind of meta commentary on the flood of obscene, pro-American content that seems to have no limits to its depravity – and in a similar yet different way, no limits to the depravity of just how cringe it is. So will you please join me in welcoming Al Hassan Elwan, POSTPOSTPOST™.

Al Hassan Elwan: Thank you everyone for having me. It’s a true honour. I’m glad we could do this before we are all imprisoned.

Shumon Basar: Maybe we will do it in prison!

Al Hassan Elwan: I guess what I’m going to say is going to feel like the kitten or the ass post that Muhannad talked about. I’ll just give you a quick download of POSTPOSTPOST™ and what it has been for the past almost three years now.

POSTPOSTPOST™ is a brand that produces publications, films, and cultural commentary. I also like to see it as a movement. It was born out of my frustration with the cultural acceptance of linear historicism, so the infamous modernism, postmodernism, and the lesser-known post-postmodernism movement of the late 1990s. This sort of periodisation has always kind of icked me as something that is somehow negatively affecting ‘discourse’, and post-postmodernism was especially dangerous as it touted a return to modernist grand narratives and authenticity discourse, which was a true prize for a neoliberal world order. So POSTPOSTPOST™ felt like the only adequately ridiculous follow up that can never be taken seriously. A bulletproof vest to sincerity.

Then, of course, there’s the more obvious twofold meaning or interpretation of POSTPOSTPOST™, which is referencing online posting, and basically our undisputed zeitgeist identifier. POSTPOSTPOST™ is basically the signpost that proclaims internet culture as no longer an outlier to mainstream culture but what drives it. This also reminds me of the conversation we had earlier about the centre and if London is the centre. I honestly couldn’t really relate to that conversation because I feel like the centre is no longer physical and the centre is online or in that virtual biome.

I even feel like things used to happen in the real world first, and then we talked about it online. But today it’s kind of the inverse. Even the Nazi salute that Elon Musk did, it felt like it happened online first and then in the so-called real world later. So, when Shumon invited me to this event, we both felt it made sense to talk about the Instagram page part of POSTPOSTPOST™, especially after 7 October or on 7 October. Especially also after what I was posting during the first couple of months before all the despair, disillusionment, and ‘doommaxxing’ took over. But to be honest, I’ve always wanted POSTPOSTPOST™ to be a window that shows the West things that I thought were important for them to see. So even before 7 October, what I was posting was coming from that angle, and not necessarily in the sense of introducing other cultures or whatever, but things that I felt were more prescient and that were not being seen.

Luckily, after what I was posting on and after 7 October, I received a lot of DMs. I wish I could have pulled them up here, but they were so far back in the archive. I received a lot of messages that said that we would have never seen anything that showed us this, mostly because my audience was largely from, as Nadja [Argyropoulou] mentioned, the family that marries itself – so they are all kind of art world liberal Los Angeles, New York people. So, 7 October didn’t really cause a shift in strategy, but it was rather a continuation. And it was just always about reporting and reporting the present moment. And I feel today Gaza is the present.

But I also really care a lot about form in the art theory sense. From Malevich and John Cage to Muhannad, great formalists have always taught us how to subvert the medium and manipulate what we are used to seeing just by playing with form, holding our attention by producing nothing. So, to me, propaganda was never about the message. It was always about how well you play with the medium. And while the meme as a medium has its unique, ever-evolving, dynamic meta-language and hyper-contextual structure, its dissemination engine runs on resonance and humour. It’s why the right can’t meme – and why the right can’t meme is itself a popular meme. Radha [D’Souza] mentioned earlier about a dissident tradition that also posed geolocation – it’s always been everywhere, whether it’s in the West or not, to also avoid the West versus rest kind of dichotomy or dilemma, as Eyal [Weizman] mentioned.

I feel like focusing on the medium and focusing on form is what really allows us to do that deeper dive. We have all witnessed Israel fumble the bag a million times, attempting humour only to get comments like ‘they’re cringing us to death’ in response – and that was the kindest comment, just on a comedy critique level. We see this happening now also with Elon Musk. I don’t know if you guys saw him yesterday with his very, also cringe to death, chainsaw. He had a moment where he said, ‘I am become meme’. Anyways, during those early months of the genocide, there was a lot that was being revealed in terms of online culture and how these dynamics play out. You could see a lot of pages that you would think would be on the front line of recording this, not mentioning it at all, and then on the other side you would see a lot of new accounts pop up to report as well. It quickly became apparent that a pro-Israel meme page couldn’t post tacky, cheesy, pro-Palestine content – which, to be honest, there is some – and expect their followers to get it as an in-joke without making it really explicit. But pro-Palestine meme pages, with zero context, would just post an Israeli on TikTok baking gluten-free cookies for the IDF, and everyone would be in on it. No one would really think that this page is being pro-Israel right now.

Unfortunately, today’s internet has also significantly limited the pervasive potential memes used to have due to the right-wing slanted algorithms and things that are currently being engineered and optimised for even more takeover by the techno-feudal overlords. We have seen various DIY tactics that try to bypass the algorithmic bias and shadow bans: from algo-break selfies and ‘Save Israel’ stickers to what Muhannad was doing to replace imagery with text. But I also feel our secret weapon remains humour and also niche humour. Specifically, I feel it’s the true end-to-end encrypted tactic, not WhatsApp, and basically the universal brand mark of those who went down the same rabbit holes we have all been down.

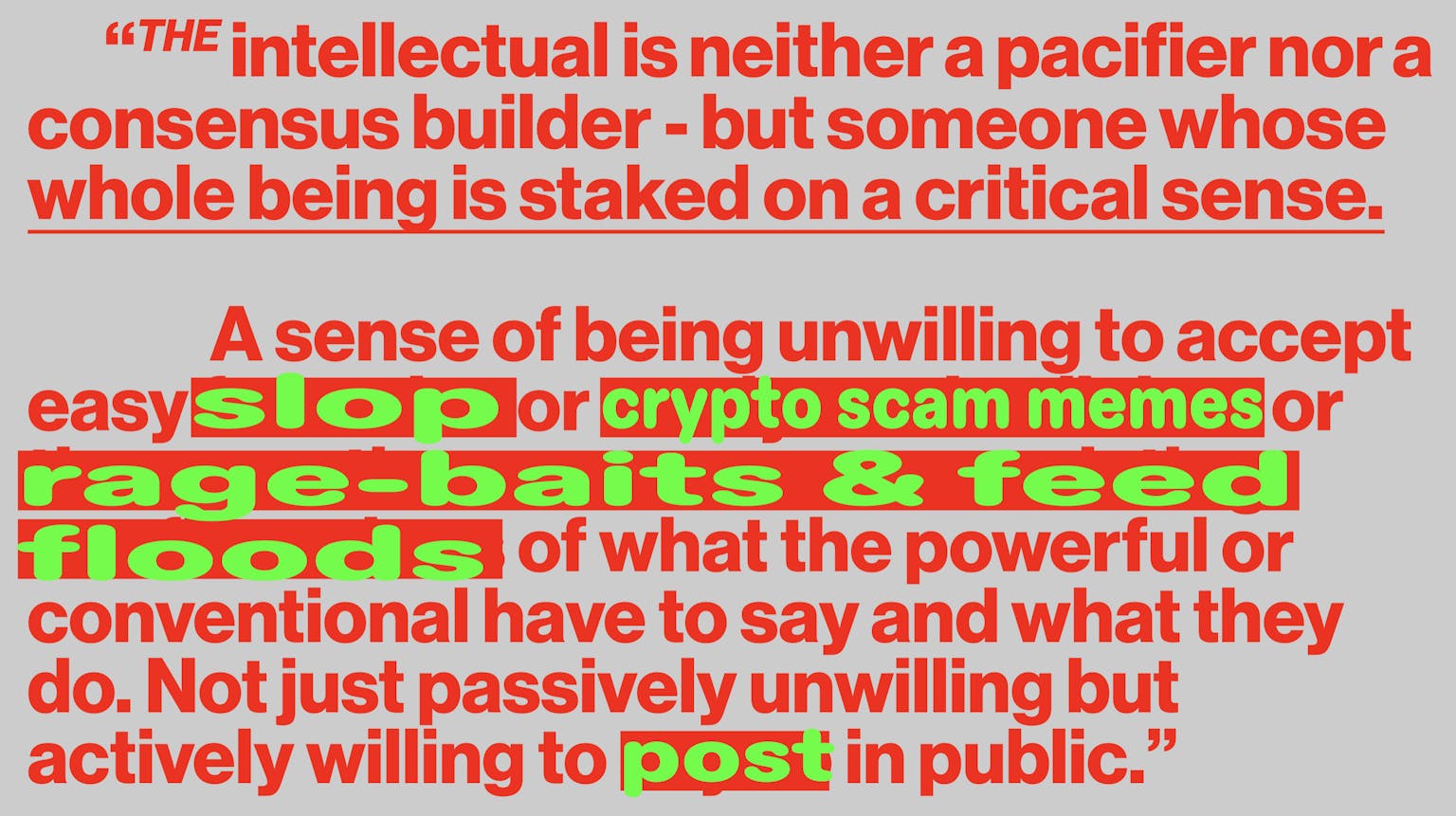

Lastly, I just want to quote the goated Edward Said:

At the bottom, the intellectual, in my sense of the word, is neither a pacifier nor a consensus builder, but someone whose whole being is staked on a critical sense, a sense of being unwilling to accept easy formulas or ready-made clichés, or the smooth, ever so accommodating confirmations of what the powerful or conventional have to say and what they do. Not just passively unwilling, but actively willing to say so in public.2

I think meme connoisseurship exemplifies this critical sense that Said talks about. If we apply that framework, we can conclude that we need to be able to tell the difference between slop and anti-slop brain rot. We need to be able to audit all the irony layers and accurately gauge the intention underneath all these meta-ironic attempts to also foresee things like ‘Hawk Tuah’ for what it is before it’s exposed as a crypto scam; to navigate cringe and post-cringe and to hold the line against rage baiting that is done by either Elon Musk or Kanye or any of those normies.

Lastly, I don’t think any of us here can really be anti-imperialist. I just think we can be anti-imperialist propagandists. I feel maybe Simone Weil was able to go actually fight in a war, but right now all the theory people are just on Instagram. There’s so much in terms of the material world that is not available to us as people who are culture operators. But propaganda is kind of like our bread and butter. It’s what we can do best. At the end of the day, craftsmanship is not just pottery. It’s basically a deeper understanding of the medium, and this is where we have leverage with whatever the medium may be – it doesn’t have to be memes or online or whatever. I think this has always been the true avant-garde and also the last line of defence.

A lot of people here probably have heard a lot about Angelus Novus, but maybe some haven’t. It’s basically this 1920 monoprint by the Swiss-German artist Paul Klee that you can see on the screen here, but it’s photoshopped onto another picture. According to Walter Benjamin, this angel is being pushed by wind, seeing the wreckage of the past, the debris, and this wind is progress, and he cannot turn around to see the future. I think when we look at all of what we are experiencing right now in terms of, let’s say, the feed as the wreckage, but also the culture as the wreckage, I think POSTPOSTPOST™ is trying to posit that maybe the wreckage was the barricades all along. I kept thinking about this when I got to Ibraaz, because I feel like this space is part of the barricades as well.

Shumon Basar: Thank you so much. Günseli Yalcinkaya contacted me a few weeks ago as there are a lot of us who are very online in London, and we are feeling very alienated because we have got nowhere to put how we are all feeling. And the timing of your message to me was exquisitely serendipitous because I was like, why don’t you come and join this discussion with us and talk about this? Günseli is my favourite internet folklorist and the person that I think many of us go to to understand internet microcultures. Please join me in welcoming Günseli.

Günseli Yalcinkaya: Hi, so off the back of what Shumon was saying: I’m a writer, researcher, artist. Shout out to Y7. I describe my practice as internet folklore because it interrogates the myths embedded within emerging technologies and the kind of platforms in which we operate. I was formerly an editor at Dazed, and Shumon was the first guest for Logged On, which is a podcast I used to run. So, I wanted to kick off this presentation with two quotes from Philip K. Dick. Firstly, because I think his commentary is especially useful in these reality bending times, but also, to reference Shumon’s essay, ‘We’re in the Endcore Now’, because we have entered our Philip K Dick era. So, the first quote:

[U]nceasingly we are bombarded with pseudo-realities manufactured by very sophisticated people using very sophisticated mechanisms. I do not distrust their motives. I distrust their power. They have a lot of it. And it is an astonishing power, that of creating whole universes, universes of the mind.3

And the second one:

The basic tool for the manipulation of reality is the manipulation of words. If you can control the meaning of words, you can control the people who must use the words.4

I think if we add images onto that, that is a very good explainer for what we are experiencing today. It’s crazy that this was written in the 1970s. In today’s ‘neural media’ landscape, to borrow a term from K Allado-McDowell, it seems that pseudo-realities are blitzing us from every angle, growing increasingly more absurd as technology advances: the reality-warping effects of social media; fake news; the meme warfare of the alt-right; the mainstreaming of conspiracy theories; and the neo-feudal futurism of Silicon Valley’s libertarianism. We have seen mass images take command of our screens and compete for our attention. They function as their own form of divination, reactionary tools to mobilise fiction to influence reality. In today’s attention economy, what we spend time on and dedicate our attention to is what forms and informs the dominant narratives. These are, of course, reinforced by the tech-industrial complex under platform capitalism, where we have seen any discourse surrounding Palestine blocked, censored, suppressed.

Yet, despite this, we have seen user-generated content thrive on platforms such as TikTok, which by all accounts began life as a social media platform in 2016 to broadcast dance routines, distinctly not as anything even remotely political. We have seen Palestinians using these platforms to broadcast the on-the-ground realities of everything that’s happened post-7 October. Again, reorientating the discourse away from the incentives of the ‘broligarchy’ – aka Zuckerberg, Musk, Gates, the PayPal Mafia, and all those other evil people – who attempt suppress these narratives through algorithms and the weaponisation of images, which clog up the feed and dominate much of the world-building that we see play out online today.

We have entered a moment in history where the contents of the images we see daily on our screens have become completely detached from any underlying truth or reality. And it’s often hard to tell whether images were created by AI or not.

So, what’s next? I think there are a few case studies that show that, by all accounts, the US is scared that western narratives are falling apart. Counter narratives are shining through the cracks also. I did want to highlight some recent examples, the first being patron saint Luigi Mangione overhauling the online discourse. We saw very recently ‘Gen Z TikTok refugees’ migrating to the Chinese platform RedNote, which was shortly followed by the success of DeepSeek, an open-source LLM. The fact that the US is rolling out million-dollar fines for anyone who downloads it indicates how much of a threat it is. I think it was last year, or the year before, that Osama bin Laden’s ‘Letter to America’ went viral on TikTok and generated over 41 million views. To quote one American Gen Z commenter: ‘I will never look at life the same, this country the same.’

So, to me, meme admins are some of the most exciting voices online right now. They are the artists, the historians, the archivists, the news reporters. The fact that I’m sitting on this stage with you three right now is incredible – these guys are genuinely the online praxis playing out in real time. At the same time, meme admins are glitching forces. They are also agnostic to institutions; so, in a positive way, they have the freedom to troll them and they can put them under fire. They are not reliant on their funding, among many other things. I think an important thing to mention here is the anonymity of a lot of meme admins today. You know, we kind of revert back to that pre-Facebook real name policy type thing, you know, that’s a good protective mechanism, one that we have been seeing used for the worse on the right-hand side of the spectrum.

When the US announced the TikTok ban at the beginning of the year, it lasted a grand total of 24 hours until it returned under Trump, only with increased censorship around pro-Palestine content. Around the same time, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Instagram is ditching human fact-checkers, and he will soon be trialling a dislike button. I think it’s important to really see how these platforms are changing on a daily basis, on an hourly basis, per minute. I also do believe, though, at the same time, there are many ways – as we have highlighted throughout the course of today – that we can really rupture these dominant narratives through, I think, the most powerful bottom-up system that we have, which is the internet.

That said, I do think that what’s becoming increasingly clear is that social media platforms no longer meet the needs of their users, while the intended use for said platforms has been upturned. We are clearly in need of these new platforms, but we don’t know what’s next. My question is: how can institutes support these virtual on-the-ground voices instead of hinder them? I think this is a great case for de-virtualisation. As Shumon mentioned a few minutes ago, I was airing some of my frustrations around a lot of people in London, like early career stage artists, musicians, creatives feeling very trapped, feeling like they don’t have any resources. There’s no finances, there’s no venues to really host these types of conversations, so I’m very happy to be here today and pick everyone’s brains.

Shumon Basar: I’m going to go straight to some plants in the audience. If I could call upon Y7, Hannah [Cobb] and Declan [Colquitt], if you have a question, that’s great. But first, I would like to ask you a question. I would say one of the questions that we have – not just for this session but I think for the entire project moving forward – is when to be online and when to be offline? And for those of you who don’t know, Y7 are a post-disciplinary duo based in Manchester with expertise in generative AI, now quantum computing, but also social media micro trends. We got to know each other because Y7 conduct a reading group in Manchester, and one of the sessions involved some of my texts and everything somehow emerged from there. I find it so interesting that for people who are deeply, deeply online, there is also this very offline aspect to what you do as a practice, as a politics, as well. So, Hannah, Declan, I wonder if you could say something about this question of when to be online, when to be offline, and what it might mean to be both things together?

Hannah Cobb: We have thought about this a lot, especially because we were involved in a political group in Manchester last year and into this year as well and it’s trying to work out how to bridge the gap and feel like you are reaching communities and people in real life, having a tangible effect on people’s lives. Bringing those people into spaces where they may not necessarily feel that they are welcome or that they belong, particularly institutions and academic spaces – as well as political spaces – hence the reading group. A big thing is to have this sense of – I’m wary about the word ‘community’ – but have a sense of feeling like people belong and can say whatever they want to say and share ideas, and also reach a broad audience via online platforms. We run a Discord channel because – thinking about the structure of the way social media works – it takes away the risks of censorship on something like Instagram or X. It kind of operates outside of that.

So, when to be online and when to be offline? I find it so hard because the two really have kind of blended into one over the past two years. It’s really hard to discern the difference, but I think that places like Discord is where we can organise meetups and can bridge that gap. It definitely feels like what Al said about the centre not being London, not being a physical place, that it’s more like a virtual space.

Declan Colquitt: Because of the contextual circumstances that have fed into its founding, it feels like Ibraaz is scrutinising every aspect of itself as it is forming. To put this in internet-native terminology, there is a theory of the ‘clearnet’, of public spaces like Instagram and social media, and then there are also ‘dark forest’ spaces like Discords and private servers. I would encourage Ibraaz, as you seem to be doing, to carefully consider its position within these frameworks and with regard to the Future Art Ecosystems research coming out of the Serpentine.

Shumon Basar: Zein Majali, we have been having an ongoing conversation. I asked you to come in and meet Lina [Lazaar] and Stephanie [Bailey], and hopefully we will be working together in different ways, but if you could maybe also just address this question about when and where to be online and offline, because I think what you do sort of creates a very interesting ouroboros between those two conditions, which of course are not two conditions but are in fact one condition.

Zein Majali: I kind of want to talk a bit about what Günseli was talking about in regard to decentralisation and the death of legacy media and the emergence of neural media in relation to the collapse of international law and democracy. I feel like Arabs have sort of been primed for this experience for a while now, since we have always been sceptical of these ideals. Declan just mentioned about the way users now go into ‘dark forest’ spaces, and this is also something that Arabs are familiar with because we have had to evade censorship within our own authoritarian governments. I feel like this priming has helped us navigate the post-7 October landscape, despite the doomerism and the heartbreak of it all. And it’s helped us manage to sway public opinion through humour, like POSTPOSTPOST™ was talking about, or sincerity, because our reality was closer to the truth. Also, we are used to using an authoritarian platform in this shifty way.

But I feel like this accelerated and increasingly decentralised experience is making us more and more schizo, and everyone having their own timeline and hyper-specific content is making us a bit insane. And while I’m aware that I’m an active participant in this meme space, I’m also aware that this culture and manic influence that we have managed to tap into will likely never amount to any policy change. So in this way, I feel like we have hit the limit of posting sometimes, which is why I’m pro dipping offline every now and then. I feel like there’s this craving for a reality check or a centre, or this sort of like reference point to bump up against. Even today, being in a room with my favourite terminally online people is immediately generative, like me and Hannah could just talk casually about something and then we end up sharing tools on generative AI. So I feel like maybe with this sort of offline convergence, it’s useful for thinking through what kind of structures or imagined structures posters, artists, and activists could come up with to – I mean, this is hopeful – achieve any material change, or at least attempt to at a time when posting is starting to feel a bit dead.

Shumon Basar: Actually, on that point about the limits of posting. After Declan, I’m going to ask Malak [Helmy] to come in because I know it’s a conversation we have had, and you are also having with Stephanie, which is a deep emotional attrition in relation to these apps. Because on the one hand, we know why they are poisonous, why they are toxic, the limits, and so on and so forth. But we also know they allow certain things to happen that simply don’t happen anywhere else.

Declan Colquitt: I just realised when I was talking that some of my thoughts had trailed off, and I just wanted to tie a bow on them. With regard to Ibraaz, I’m leaving no stone unturned and really considering its position on a lot of things and, you know, emerging very thoughtfully. Even things like having its own podcast studio that is available to use for comrades and like-minded people, as well as its own private server, having its own Discord, and having its own kind of digital infrastructure, as well as the bricks and mortar. I think this is really valuable, also in terms of the ways it relates and interacts with artists. As I said before, the Future Art Ecosystems research that’s happening at Serpentine would be really valuable for establishing autonomous models, as this will be an institution that comes under a lot of scrutiny. So being as self-reliant as we can be, I think, is a super important thing. I just wanted to add a slightly more articulate conclusion to my earlier ramblings.

Malak Helmy: What I’ve been thinking about a lot over the past year and a half is, I suppose, this critical mass that you reach in terms of posting, and I guess reaching a certain kind of emotional peak that you want to get to, perhaps even within yourself, but also with everybody else online. But then how do you go from that space into what you were saying – how does that also then form something within the world, or within the law? Where does that space come in? I’ve also been thinking a lot about people who also do that daily work, like personal rights advocacy and human rights advocacy, who are doing that work every day. I’m based in Egypt, so I’ve been really thinking about people who have been doing that for the last 10 years on a daily basis and thinking about the importance between how you hold a space and online posting, and thinking about your responsibility. I think it’s very important to hold those two spaces together, and to remember exactly where your body is. Your physical body and physical space are really important. And as much as the centre is online, it’s really important that it isn’t, and it’s vital that we always remember that. It’s a tool to help us go offline and to do things, and that’s the hardest part, actually, because that’s when things get really scary. And that’s not just going on weekly protests. I’m always thinking about what’s that next point when you are also sort of willing to sacrifice a little bit more. Something along these lines.

Shumon Basar: Thank you, and now my last plant, Jaya [Klara Brekke]. I would like to bring you in here. There’s one way of telling the history of the internet, which would be something like: it started out with a sort of a dream of maximum decentralisation, maximum multi-centralisation, etc. Fast forward 30 years to the anniversary of the World Wide Web, and Tim Berners-Lee basically said, ‘I wish I hadn’t given this fucking thing to you, and if I could take it back, I would’, which was sort of an admission of just how far his child had gone in the absolute opposite direction of what he had intended. Of course, in that sense we live in a kind of FANG (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google) world. But FANG doesn’t also take into account, I guess, the other technological behemoths, many of which are in China now. But by and large the narrative has been less decentralisation, more centralisation. Jaya is one of the world experts on decentralisation via blockchain and the politics of the blockchain. So, Jaya, I wonder if you have something you would like to say regarding our conversation?

Jaya Klara Brekke: I have so much to say, but I’m also aware that I’m on a panel tomorrow that’s about organisation, and I am going to talk a lot about decentralisation and a lot about technology and the failures of both. In the tech industry, concepts of decentralisation have brought so many ideal dreams of the ways that humans could live differently together. Those dreams have turned into total nightmares, and we are kind of at a climax of that right now, with also, effectively, a kind of tech coup happening in the US; a total takeover and destruction of some semblance of democratic institutions.

Without saying everything that I’m going to say tomorrow now, I think one bit that feels like it’s missing from the conversation is financial markets, and how posting online is also feeding into the business model of the platforms themselves. Even when Musk goes out and does the gestures that he does, it’s to capture headlines, and those headlines have market effects. And if there’s two things that we know very well about Trump and Musk, it’s that they are exceptionally good at manipulating markets. They do it over and over again and they are getting away with it, and it’s absolutely infuriating and insane. At this point, there is a lot of, let’s say, capturing of online spaces with content, making sure that we are feeding the algorithm and keeping a story alive is important to a certain degree. But we have also reached a point now where exactly the kind of platforms that we choose to use matters more than ever before.

This is a bit of a vindication of the free and open-source software movement. I mean, honestly, nothing of what is happening today is a mystery. A lot of this stuff, when it comes to tech, we knew from the early days. Even Tim Berners-Lee in the 1980s had people who were looking at the designs of the internet and they were like, holy shit, this is not going to go well. Already, people knew this was going to become a vehicle for mass surveillance and it’s a problem. It’s one of those oopsies.

About the core protocol of the internet. It was literally designed in a kind of trusted environment where people were like, ‘Okay, we are academics, we are going to share some information with one another and isn’t this going to produce a nice and wonderful world’, completely forgetting that actually, once you deploy those networks across the entire world, those networks become a surface for attack and exploitation, and that’s exactly what happened. Then we have seen a business model being built on top of the surveillance machine, and the kind of consequences of that business model on people’s mental health, physical health, and so on. I mean, when you invited me to come and talk on decentralisation and contribute to this question of organisation, I was like, I’m going to try and come up with something positive – cliffhanger for tomorrow, there will be some positivity there – but it’s really about the climax of total catastrophe of core infrastructures of society right now.

I won’t give any more away. But I did want to just ask a question because I’m genuinely curious about this. What does online posting and online life do to the quality of being offline? It’s not so much the question of what should be online, what should go offline, but more like: how is the fact that we are posting so much online, changing the quality of relationships externally; maybe even making them more valuable in certain circumstances, and opening up a different conviviality? What does it mean?

Shumon Basar: I would love Al to answer that. When you switch off your phone, how does it feel?

Al Hassan Elwan: Maybe this is something that I haven’t felt, but I have heard it said before that being online kind of negatively affects being offline. But to be honest, I think it’s usually the opposite. I mean, the easiest example is most of us wouldn’t have been here if it wasn’t for us being online. But I do want to also clarify something in terms of what I said about the centre being online and so on. Me saying that does not mean that we have to be at the centre; it’s acknowledging it but also making sure that we are not there all the time. Offline is, in my opinion, tremendously important as well. And to your point about surveillance and it already being something that we could foresee from the 1980s, maybe this could be a question that we also have for you, if you think that there is merit to the idea that there is resistance in the grasping of meme culture? I feel like I consistently see, for lack of a better term, the system failing to get that. I don’t even know how to describe it – it’s like you get a joke and they don’t, and I think that’s something we can try to hold the line on.

Muhannad Hariri: There’s a way to joke about how to answer that, which is that I would have finished my thesis last year. Honestly, I think I’ve written over 2,000 posts and they’re all just chunks of words. I never really thought about that, but it’s a really boring place. If you go to my page on Instagram, it’s just text. I’ve started using colours now, just to jazz it up. But it’s just blocks of text, which for me was important. But more important than that, is that – at least the way I’ve been doing things – it’s literally a place to think out loud about everything, and I often contradict myself. I often take things back. I fight. People fight with me. I don’t fight back, but they like to fight with me, because I don’t fight back. For me, it’s just like a collective dream reflection space that constantly shapes what I’m seeing outside of the online world, which is my desk and my cats, that’s all I know. I do have a rich offline life, but it’s informed by all the things I see, and that’s how I like to use ‘the gram’.

Nesrine Malik: Such a great panel. I never thought I’d hear the words ‘meme connoisseurship exemplifies Edward Said’s genius’, but there we are. I’m a journalist, and what I have noticed is that posting, as has been discussed here, applies to everything. It applies to journalism, news reports, long-form, short-form memes. Everything is being consumed as online content.

I have a question about the erosion of physical space because we are talking about online or offline, but we haven’t really talked about what has happened to the offline world, particularly since the pandemic, and the ability to opt out and retreat into video calls, remote meetings, voice memos, etc. I don’t think we have reckoned with how much that has disempowered people, atomised them, removed their sense of agency, their sense of solace, removed group collective conversation – even the water cooler moment has gone. The only times over the past year and a bit since 7 October that I felt that people had a sense of surprise in meeting others and knowing that they felt the same way, was on university campuses, streets, and in classrooms. And any time those places incurred upon power structures, they were immediately snatched back. University campuses went remote, they went online, and the streets were securitised very quickly. So, there’s a kind of political-global pandemic/securitisation dimension to this that poses an additional challenge, perhaps, to going offline than would have been the case four or five years ago.

Shumon Basar: Günseli is that something that you recognise?

Günseli Yalcinkaya: It’s a really tricky one to unpack, I think. Maybe to go back to the thing about neural media and the complete unpacking of power from legacy media, which I think the pandemic also very much shone a light on, I really see it as these two kinds of polarising forces fighting against each other. Because on the one hand, it’s exactly as you said, it’s been a way to up censorship, up surveillance. But I guess as a kind of natural response to that, we have also been seeing some really exciting pockets of discourse come up, and to kind of second both your points, I’ve had more meaningful conversations online – maybe I don’t get out enough – than I have had offline. Maybe that’s because if you work a nine-to-five job or you are in these institutions, things do necessarily get censored or you do find yourself having to censor yourself in any kind of societal way, and this is my really positive spin on this.

There is something about being virtual that does take away those social codes, which I feel is also very liberating. But Instagram, TikTok: are these the places to do it? I think we are all in general agreement that these places are ‘so over’, to quote internet speak, but we haven’t all kind of agreed on a place yet. Maybe because of that kind of fractured sense of online identity, we are almost retroactively going back to what Web 1.0 was. I hope there’ll be more freedom like there was in Web 1.0. I don’t quite think so, but TBC, I guess.

Mona Chalabi: Just a quick comment. I think so far Jonas [Staal] has been the only person to mention disability. And I think that’s really, really important when we are talking about online versus offline spaces. Very often when online spaces are done right, they can be much more accessible than some offline spaces. So that just feels really important, especially again in the context of Palestine. One of the many reasons for which Gaza is so revolutionary is because it has been this mass disabling event. I hope that Ibraaz continues to centre disability as it continues to build its online and offline spaces.

Ibrahim Mahama, Sumayya Vally

Alia Al Ghussain and Matt Mahmoudi, hosted by Jaya Klara Brekke

Al Hassan Elwan, Günseli Yalcinkaya & Shumon Basar