- Mission Statement

Firestarter

Francesca Albanese

Mission Statement 00: Why Now?

This is a lightly edited transcript of the introductory session of Ibraaz Mission Gathering 00: Why Now? which took place on 21–22 February 2025.

Speakers: Lina Lazaar (Ibraaz Founder & Director), Stephanie Bailey (Ibraaz Publishing), Shumon Basar (Ibraaz Public Programme Launch)

Lina Lazaar: Thank you all for being here. We’re so thrilled to welcome you to what I hope is going to be the first of many visits to Ibraaz in its new home in London. For those of you that don’t know me, my name is Lina Lazaar and I am the founder of Ibraaz and the vice president of the Kamel Lazar Foundation (KLF), an organisation that was established by my father back in 2004 in Geneva, Switzerland. Before we delve into all things related to Ibraaz, I thought I could give you some background on the KLF, which has been dedicated to supporting visual culture, knowledge production, and the building of diverse and interconnected ecosystems intended on serving ‘Arab culture’. I say this with all humility, but it’s only now that we’ve reached our 20–year anniversary that we can really reflect on the work that’s been done, where we’ve had impact, and where we need to double our efforts.

Although headquartered in Geneva, the KLF has really taken all its inspiration from its North African heritage. We have offices and a team in Tunis, Tunisia, at the intersection of Africa, Europe and the Middle East. This unique location has given birth to wide-ranging histories, multiple linguistic influences, religious diversity, and very deep culinary and community traditions. What started off as a passion for collecting art, very quickly transformed into more structured and extensive support for artists. Over time, this developed into hosting exhibitions and biennials, discursive symposiums, and a very small art centre in Tunis (B7L9), as well as a whole range of developmental activities. It’s very much through that journey of transformation that Ibraaz was first conceived back in 2011 in a coffee shop in Tunis.

For those of you who don’t know Arabic, Ibraaz literally means ‘to shine a light on’, which was something that we cared very deeply about back in 2011, when the entire world had its eyes focused on the political movements that were unfolding across North Africa and the Middle East. At the time, very few people were engaged in exploring the Arab world’s visual culture, let alone trying to really challenge, define, and understand what the Arab world is and could be.

Ibraaz quickly grew and became a prominent online publication platform – one which, we’re very proud to say, published over 100 essays and gathered the most incredible community of over 350 contributors from all over the world. I think this community of contributors that we built from the ground up was Ibraaz’s most precious asset, and I’m so thrilled to see that many former Ibraazis are here today.

Aside from its community, Ibraaz really built a whole range of global institutional partnerships, and slowly it turned from a platform for visual arts from North Africa and the Middle East to a platform for visual culture from North Africa, the Middle East, and beyond; which brings us to the present moment and why we’re all convening here today. In today’s landscape, I think editorial platforms alone aren’t enough, and that we really need find ways of blending active and robust content with a real-life or real-world presence. If we’ve learned anything in this post-pandemic world, it is that physical spaces do matter – I don’t think anything beats the ability to gather together in-person. I think physical spaces are still very much the best way to create and cultivate human connection, and it’s with that very realisation that in the spring of 2023, again in another coffee shop in Tunisia, that we started thinking of how to reimagine Ibraaz, and how it would be possible give it a physical manifestation. This is where we’ve landed.

It would be remiss of me not mention the urgency that has gotten us to this point, which has been very much influenced by the gravity of the present moment. I would say that both our intention and ambition has been massively shaped by the multiple crises that have engulfed our world in the past few years. While I have been viscerally affected by the devastation in Gaza, I’m equally conscious that there are many other horrors and crises afflicting other parts of the world, which are linked to a huge rise of radical political movements and an unbearable climate of intolerance, a lack of acceptance and empathy, and, dare I say, hatefulness.

It’s with that realisation that we have, like many of you, gone through the full cycle of grief. We’ve wept, we’ve protested, we’ve donated, we’ve debated, we’ve fought, and we’ve fought some more. Then we quickly realised that our fight wasn’t going to be won, nor was it going to be fought in the traditional sense. It needed to be waged differently. We’ve also learnt the harsh reality of this world. At best, I think we were quite naive – and at worst foolish – to have thought that the institutions we’ve traditionally relied on for support, moral clarity, justice, and for, quite frankly, the advancement of our common humanity, would respond. In fact, they have done the opposite, and perhaps even with intent and by design. We’ve had to reckon with this pretty sad conclusion. One which has forced us to gather ourselves, and think long and hard about how we’re going to plan, collectively, for the future.

So here we gather today. I thank you wholeheartedly for being here, it really means the world to us. In advance, I want to thank you for your generosity and for what we call in Arabic ‘niyyah’, meaning your intention and partnership. Because I genuinely feel and get the sense that a lot of good things will come of this. And on that note, I will leave the floor to my wonderful collaborators, Stephanie and Shumon. Thank you.

Stephanie Bailey: Thank you, Lina. Thank you for your vision as well. And thank you to everyone here who trusted us with the invitation to join us today. And thank you to everyone who helped and is right now helping make this gathering possible. Shout out to Louise [Oram], our project manager. I just want to say a few words.

When Lina first showed me the building last winter, after years of discussing Ibraaz’s revival, I remember having thoughts and reactions I’m sure many of you have had. Among them: is a space in London really what this moment needs? Standing in this hall, I thought about what we’ve witnessed since October 2023 alone: from the genocide in Palestine to the protests against it and the purges against those speaking out – all amplifications of the violence that defined every UN Security Council veto in the last 460 plus days, and a reminder of how genocide is baked into the project of the nation-state, an instrument of colonial modernity (as Arif Dirlik described it) which, as W. E. B. Du Bois and Si-Lan Chen observed, is defined by a clear division that boils down to who or what is in and out.

And I remembered the five years we spent at Ibraaz feverishly processing essays, reflections, artist projects, and conversations, amid a post-Spring realignment, as the neoliberal counter-revolution continued on its long march towards its unhinged present-day unmasking.

The core idea that defined Ibraaz back then as a predominately editorial platform for visual culture in and around North Africa and the Middle East, was that the practice came first: which is to say, we did not want to define or impose ideas and politics around an artist’s work, but rather engage with its particular terms and syntax. This responded to the tendency at the time to pigeonhole artists from the Arab world – and beyond, for that matter – as spokespeople or ambassadors for their region or country, whether or not this was the artist’s concern, which limited or reduced discussions they intended to generate.

Our rationale, then, was that the discursive frame was not something that could be applied readymade: it was something to look for and construct. We needed to develop a methodology for perceiving, if not creating alternative frameworks through which to perceive, and thus engage with histories and conditions, both through and beyond the material politics that have defined our overlapping, intersectional, and sometimes oppositional realities. This approach extended to how Ibraaz was built by networking our networks: from our editors, editorial correspondents, and contributors, many of whom are in this room, to our readers. Not to mention our scope, which operated under the mandate that we would eventually drop our regional tagline altogether, as a global platform operating from another global perspective.

All of which brings us to this building, and everything it represents, historically and contextually: a frame with a capital F, when you think about the kinds of institutions that normally inhabit spaces, not to mention cities, like this – and Shumon and Sumayya Vally, our resident architect, will share more about the architecture and how Ibraaz plans to grow into it.

Standing in this hall for that first time, as Lina described the urgency to create a space for culture that was courageous enough to confront the present, I remember taking a breath and thinking, okay: how do we make this work for the moment? If there was ever a chance to concretely test if space can be decolonised – and I say this word recognising the contention it triggers – this is it.

That’s where this meeting comes in. The idea is not to have a discussion between ‘you’ and ‘Ibraaz’. Rather, the idea is to share the questions we have been asking ourselves in order to think together about tactics and strategies to not only navigate the present – bearing in mind that history and the future ultimately reside in the now – but perhaps even redefine it.

Our hope is that through these exchanges, Ibraaz can sharpen its mandate as it unfolds as an institution dedicated to platforming art and culture from the ‘Global South’, in a way that reminds me very much of how Ibraaz evolved in its first incarnation: responsively, intuitively, and at times amorphously, yet with an internal logic that emerged through that flow – which is not to say mistakes weren’t made.

That brings us back to this meeting and the questions it poses. Rather than define or prescribe a structure before establishing it, so as to avoid replicating or reproducing the dynamics inscribed into the culture industry, we wanted to see what emerges through our work with the space.

This meeting is part of that work. So thank you all once again for joining us. With that, I hand it over to Shumon.

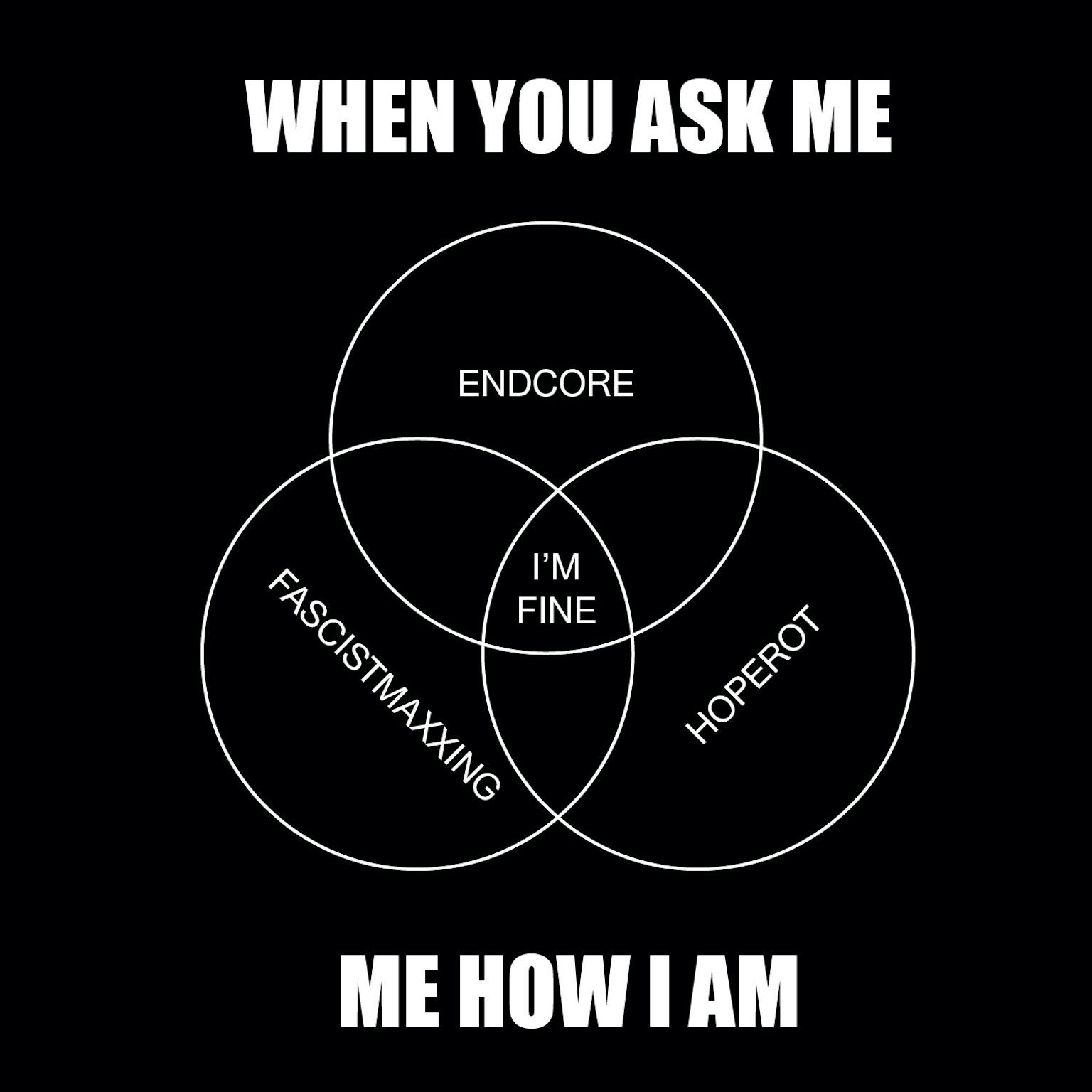

Shumon Basar: To develop what both Lina and Stephanie said about why it’s important that you’re all here and what this potentially means: my true friends know that one of my most loathed questions to be asked is how are you? Now, instead of looking vacantly into space with a deathly stare, I show a Venn diagram that I’ve drawn up. It’s three circles that overlap. One circle says ‘Endcore’, a neologism I coined to describe the feeling that it’s the end of the world, but also at the same time that the end never actually arrives. The second circle says ‘Fascistmaxxing’, which refers to the unmasking and unmaking of the world that has become vividly clear. Fascistmaxxxing is when power has shed the pretence of shame. Shame is passé now, as is decency. And, the last circle is ‘Hoperot’, which is a bit like brain rot, but for hope. Hope today feels like a scarce resource. Sometimes I have no hope. And then I notice that the epilogue to Pankaj Mishra’s new book, The World After Gaza (2025), is titled ‘Hope in a Dark Time’.

I also remember bell hooks once said that ‘hope is political’. To abandon hope is maybe an unaffordable privilege because, as Norman Finkelstein said, if we do not try, then nothing will ever change. Or as Gramsci famously put it, we need ‘pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will’.

So gathering you all here like this – to think together, to feel together, to plot together, to mourn together – is optimism of the will. You represent a neurological, moral, and imaginative constellation of possibilities. We’re truly grateful for you to be here with us now.

I’m reminded of a tweet that I saw a couple of months ago which simply said: ‘Imagine a university staffed with everybody that’s been fired in the last 16 months’ – which would basically be the best university in the world. And FYI, at the centre of my Venn diagram of three circles is that most ubiquitous of English phrases: ‘I’m fine.'

With that, it gives me great pleasure to start our inaugural gathering with a very special guest. Please welcome Francesca Albanese.

Francesca Albanese

Stephanie Bailey, Radha D’Souza, Adam Broomberg, Françoise Vergès, Anjalika Sagar, Nour Yakoub, Gaurav Sinha