Interviews

Transmission Systems

Raed Yassin in conversation with Stephanie Bailey

In this conversation, Raed Yassin talks about the way his work encourages audiences and participants to become actively engaged in the interpretation and dissemination of an artwork and the ideas that feed into its construction. This conversation took place at the Delfina Foundation in March 2014, forming part of its residency programme and exhibition, The Politics of Food. The conversation begins with a discussion around two performances Yassin devised during his time as a Delfina resident, and expands into projects that explore the networks within which artworks are produced. Projects discussed include The Impossible Works of Raed Yassin (2013–ongoing), in which the artist invited curators to take the place of the object itself in an exhibition context, thus narrating to an audience the idea of a work that does not exist. Yassin also discusses China (2012) and Yassin Dynasty (2013) – vases that were produced out of a chain of commissions.

Stephanie Bailey: Let's start with the residency you completed at the Delfina Foundation, which was based around the theme of The Politics of Food (2014). As part of this, you staged an interactive performance, What Tongues? (2014) with curator Beate Schüler. What was this performance and how was it conceived?

RY: Well it started after I met Beate Schüler, a curator from Germany. We both had a common interest in food, and its relation to art. While we were talking, I tried to explain a dish to her: a Lebanese dish called Mulukhiyah. A few days later, after I went back to Beirut, I sent her a photo of Mulukhiyah to show her what it is. The same day she started to send me photos through WhatsApp of what she was eating: I sent her a picture of my lunch, and then she sent me a picture of her dinner. We kept sending pictures to each other and we started to develop this relationship around food, which was funny. At first it felt very weird, because I felt very intimate with a person that I didn't know just by knowing what she was eating three times a day.

SB: You were messaging each other every day?

RY: Yes. Then she started to develop some kind of jealousy saying things like, 'I envy you', 'I want to eat this', or 'where are you?...'

SB: ...where's your meal? What are you having?

RY: I cannot describe it. Gradually, we wanted to know how the food smelled and in what social situation these meals were taken. So basically, though the starting point of this collaboration was food, it went more into the realm of human feelings, which for me is more important.

SB: How long did this exchange go on for before you devised the collaboration that took place at Delfina?

RY: After about three months doing this daily, we started to think about developing this into a performance. Beate and I met here at Delfina to develop ideas of how to conduct the performance: how it was going to happen, what ideas we should start with and how. Then we did a lot of tests with people we didn't know – Beate gave me some numbers for her friends I hadn't met and we started to do these tests. Then, we discovered after doing two days of testing that it was useless. The actual performance would have to be improvised because each interaction was really different: everybody has a different interest, different types of photos on their mobiles, different responses.

So for the actual performance we invited people to make reservations. We invited people to come to the space by sending an email to them and announcing it, and we told them that they had to reserve two slots, each slot being half an hour. We asked for their numbers and then we asked if they had a smart phone or if they had downloaded WhatsApp but we didn't say what would happen. When making their reservations all we told them was that they had to leave their numbers and they were told to make sure that they had WhatsApp through their emails. We did this performance in this format because I wanted to mirror the relationship that I had with Beate.

When the audience arrived they sat in chairs here and the room was split into two halves. The door of the kitchen was a little bit open and there were vegetables boiling because we wanted to make a risotto at night for us to eat and we thought it would be nice just to have a stock cooking during the performance, which was six hours in duration. And basically people came in and they started to get messages on their phones from us.

SB: And where were you both?

RY: We were in the building but they couldn't see us, so our relation with them was only through the phone. And then we tried to actually establish a relationship with each participant in there.

SB: And how did you establish that relationship when visitors entered?

RY: It depended on the people, actually, because some people are easy to communicate with and others are not. Some people were bored but others who were just used to this kind of social networking and so were more open. In some cases, we started with food but then some people were sending photos of their boyfriends or girlfriends, for instance, and others really got into a sexual conversation from the beginning, which was cool. So in the end we decided on improvisation: and the result was that every performance with each participant was very different from the other.

For me, that's interesting because there was no way any moment in this performance was the same: each one was individual so it really became about the development of a relationship between people. With some it took more time, of course. But this was a kind of technicality of this specific performance. To make it more radical, we could do a performance with people for three months, for example.

SB: I wanted to think about the composed improvisation – performances that allow for measures of unpredictability though they are undertaken with parameters that are clearly defined. This relates to The Raed Yassin CookSongBook (2014), which you also worked on as part of the Delfina residency. Could you describe what the The Raed Yassin CookSongBook is, first of all?

RY: The The Raed Yassin CookSongBook came out of this idea that there are always cookbooks and songbooks and I was interested in making a song and cookbook together. And I have always wanted to work with the singer called Ute Wassermann because I think she is a really amazing vocalist and musician. Since I was doing a residency that was themed around food, I thought it would be cool to write recipes for a solo voice, and Ute sang these food recipes.

SB: But you didn't just write the recipes you presented them as graphic scores through your use of typography: the type sets you chose and the fonts and the sizes you used…

RY: Yes. I had to write something with the graphic scores in mind so she could read it not only as text but as a musical score also. So I wrote this graphic score, which looks so weird and sometimes very confusing, with a lot of signs, and just imagined how sound could be interpreted by letters and punctuation.

SB: Like the sounds of a knife represented as the forward slashes?

RY: Yes. For example, I always wrote salmon roe in very elegant fonts, and Ute thought that she should sing these fonts in an operatic way. Of course, I wrote this imagining that she would sing it – it was all written for her voice. Ute uses a lot of whistles and objects while singing so I was very interested in thinking about what she could do, and how we could play with her voice and its abilities. When we had the rehearsals, it wasn't really just about giving her the score and telling her to do whatever she wanted, though. She was asking me questions, too.

SB: And for these scores Cornelius Cardew was a big influence, right?

RY: I was always interested in graphic scores because they are really located at the intersection between art and music. Each composer created an idea of how to make new compositions. It's all for the form. When you see you a graphic score, you don't know how you should read it. There's always the question: how should I read this?

In this regard, Cornelius Cardew is one of my heroes, actually, and I was so honoured that I played with his collaborators on 5 March at a performance I staged at Café OTO – Cardew was part of the group AMM and I played with two members from it: Eddie Prevost and John Tilbury. There was a big debate about Cornelius Cardew's practice because he's a composer who has always been very interested in interpretation and who didn't just eliminate the personality of the musician like other composers do by saying: 'I have this you perform it and then you leave'. He was interested in this bridge between the composer and the musician so he made a lot of music based on graphic scores in which each musician could interpret the same score differently.

SB: Because it's not actually musical notes – it's just lines and shapes?

RY: Yes. The most beautiful graphic score I have seen is his composition Treatise (1967): 148 pages that look like Russian constructivism. They are all made into geometric shapes and circles and lines. But he always put these five lines of music on the bottom just to insist that this should be interpreted musically. And there are so many albums of this – everybody comes and they interpret it and each time it just sounds so different.

SB: This reminds me about what you once said to me about Bach's harpsichord compositions: that this was a project that you had in your mind to invite musicians to interpret harpsichord compositions.

RY: To play Bach with feelings!

SB: Could you talk about this a little bit and how it relates to your practice?

RY: We're talking a lot about music, so I guess it's important to underline that I'm an artist and a musician. I think this is somehow misinterpreted in the art world, because the two worlds – art and music – are so different. But there are intersections between them, of course. For me, the The Raed Yassin CookSongBook is an art piece but it's also in between.

In thinking about Bach's music, these harpsichord compositions were written before the invention of the piano. They were intended for the harpsichord, which is an instrument that is very mechanical: the sound doesn't have dynamics: there's no loud or low, or even any sense of feeling. This is because of the mechanisms of the instrument itself – it produces a sound that is mechanical and flat. So I wanted to film musicians playing these harpsichord compositions on a piano but with extreme feelings – like filling Bach with anger: Prelude or the Goldberg Variations with extreme happiness and extreme anger, for example – to see how the composition alters with this treatment.

SB: That makes me think also about the WhatsApp performance and how it started – this growing relationship between you and Beate through which feelings were extracted from an exchange that was essentially mediated by a machine.

RY: Exactly, but there was an interesting part with this WhatsApp work: there's the question of the screen as a mirror. When you are communicating through WhatsApp, you are speaking a little bit to yourself or writing to yourself in a way. It's like trying to explain your ideas to yourself.

SB: Right. Going back to Cornelius Cardew, it's taking a musical score that, even though it somehow communicates a fixed structure, it is still open to interpretation. This is kind of what happened with Ute's work on the CookSongBook. Because she was interpreting it with the capabilities of her voice whilst staying within the parameters that you had laid out for her. This is super interesting because it relates to The Impossible Works of Raed Yassin (2013–ongoing).

RY: Yes.

SB: Maybe it would be worth you describing this work a little bit first…

RY: So this is connected to the idea of how I started to develop my relationship to art and performance. For this performance, I invited five curators to perform and speak about impossible works of mine that don't exist and that would be impossible to execute. I wanted the curators to write about these works so I started developing each project with each curator in a period of time between four to six months. First, I asked them to come up with an idea, but some of them didn't want this. Some wanted me to put forward an idea and then start from there. But I didn't want to give everybody the idea because I didn't want all the ideas coming from the same source. Nevertheless, through discussion, I started to develop the shape of these impossible works with each curator.

The performance took place in an empty white exhibition space. It was the duration of an opening – an opening in Beirut is between 6pm and 9pm and so I used this duration of three hours. Each of the curators was in a different space, doing their performances while I was ushering people to listen to the work. The curators were like video projectors on loop.

SB: Did the curators have pre-written pieces and then just repeat themselves or was it improvisation?

RY: I told them not to have any papers with them. Some of them just needed notes to remember the points of departure. The projects varied between 5 to 30 minutes. The piece written by Rasha Salti was called 'Blowback', and what we wanted to do was to re-enact 9/11 on the Burj Khalifa. But as this was about the twin towers, we would have to build another one!

SB: How did the audience respond to The Impossible Works of Raed Yassin?

RY: I don't know. Some of them liked it, some didn't, some said it was interesting, some of them said it was shit. But that's good. Nobody should agree. If there's a piece of work that everyone agrees is cool, then it's not cool. If it's not controversial enough, then there is something wrong. That's my idea.

SB: Another thing that comes out of this is transmission and exchange. With The Raed Yassin CookSongBook you were transmitting a composition to Ute, who would then transmit that composition back to you, which you would then transmit to wider audience. There is a similar kind of movement in The Impossible Works of Raed Yassin. I wanted to think about this in relation to a piece of writing you did for the MaerzMusik festival...

RY: MaerzMusik is a music festival that happens in Berlin for contemporary music. They invited me to present a text, and they were expecting an essay about contemporary music practices in the Arab world. But I think 'historically' there are no contemporary music practices in the Arab world. There are a few attempts nowadays. For example, the IRTIJAL festival that my friends and I organize each year in Beirut, presents music like this and it's now in its 14th year. There is also an electronic music festival in Cairo, which is cool and presents some of these works, but Irtijal is more radical in presenting free jazz and free form composition and improvisation and other styles like that.

So it was funny for me to write about contemporary music practices in the Arab world, so I decided to write a piece of fiction. I wrote five sections about events that had happened parallel to very famous compositions. For example, I said the first piece of contemporary classical music I heard in my life was when I was running in the fields in the south of Lebanon. It was such beautiful weather and I was lying in the wheat and I was looking in the sky and there were two white lines cutting across the sky – and for those who don't know, these were two Israeli planes just passing by: we had this almost every day in the south of Lebanon. These planes would break the sound barrier and would make these loud sounds all the time and this would always affect the people. We got used to it but then whenever we would see this line we knew what was going to happen. So I said that this was my first encounter with contemporary music: this breaking of the sound barrier in Lebanon performed by the IDF. This was my first piece. This section is called 'You Will Always Remember Your First Time.'

Amid these stores, I also spoke about a very interesting sonic poet from the 1970s that the Lebanese art and poetry scene did not take seriously: they thought he was crazy but I think he is a genius. His name is Adel Fakhoury and he started something called electronic poetry, which was actually the equivalent to sonic poetry in Europe. He started this in the 70s but people think he's crazy because he used sounds and graphics to compose his poems. He is also a philosopher: he teaches logic in universities and he's a very interesting character. He went from Beirut to be a priest in Germany but he came back as a philosopher and he started to write books about mathematical logic.

I also wrote about my friend Mazen Kerbaj who did this amazing piece called Starry Night (2006) – I think it's one of the most amazing pieces written in music, honestly. Not because he is my friend. During July's war in 2006, Mazen sat on his balcony and played a trumpet improvisation during Israeli air raids on Beirut. It was trumpet versus bombs, and I thought this was really amazing. He made a blog during the war – he's a comic artist and he made all these drawings and posted sounds and recordings during July's war as a kind of resistance.

SB: Then you describe a memory framed by John Cage's silent piece 4'33" (1952).

RY: This is actually a true story. I describe a very beautiful scene when we were running in the fields, which we used to do a lot because there was no other entertainment in the south of Lebanon. And the Israelis had planted a lot of cluster bombs and land mines. Each week, a kid died because they found some object and had touched it and it had exploded. I was describing running after my friend, who was called Mohammed al-Borasayn, which means 'Mohammed of two heads' because he had a very big head and each time we would slip into a small space to get somewhere else he would always get stuck his head stuck! So this one time, Mohammed was running faster than me and he stepped on a landmine and it exploded. I couldn't hear for a long time after the explosion, so I named this silence after 4'33" by John Cage.

SB: And this was then turned into a choral composition titled 'Music based on a true story based on a true story' by Grégory d'Hoop in 2013. How you feel about the appropriation of this text and its alteration into a composition?

RY: I don't know. I haven't heard it. I've seen the composition and I am interested in the spatial aspect that he introduced because he kind of turned the story into a choral piece, which I found very interesting. He split the text for two groups to sing: one is indoors, one is outdoors – so there's people inside and people outside singing. I haven't heard it, it will be recorded soon.

SB: But the inside-outside is also interesting because it's breaking down the boundary in between, which reminds me of the screen and the WhatsApp performance, not to mention the building of relation in your work. I think in some ways that goes back to the idea of interpretation and how interpretation becomes an object in your practice and in that you give space for your actions or your productions to be interpreted in their own right by others, be they artists or audience members.

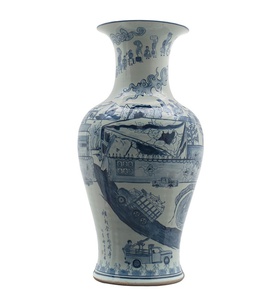

RY: Yeah, I am so interested in this idea: commissioning work and letting go. It is relaxing for me because I relinquish control and get to work with materials that I really don't know much about. For example, once I did this project with porcelain in China and it was a series of vases called China (2012), in which I presented scenes from the Lebanese Civil War on vases produced in China. Then I made a new series of vases, which were a derivative from China called Yassin Dynasty (2013). It was really a cycle of commissions. First, I interviewed fighters and then I talked with them about how they described the battlefield – how was it, what did they see, how was it for them? Then I made the composition of how it looks and then I asked a Lebanese painter to make these compositions in the Persian miniature style and then these designs were given to master in China to interpret. There was this guy who just drew the painting and made the painting in free hand and there were others who used the techniques of copying exactly. I was interested in how the object of art is a living organism that changes from phase to phase. For me, this is interesting because then art becomes a social body – it moves and it changes by what's around it and this never ends. That's why I did this Yassin Dynasty. I don't know how many vases there will be because I am still producing more.

SB: But this was an interesting project actually and this is where we met at Art Dubai in 2012, when it was being shown as part of the Abraaj Group Art Prize. Then, you told me that you would only have only produced an object like this – a vase – in a context like this: the art fair. And that reminds me of what you said about the conspiracy as the artwork – you turned those vases into subtle critiques in some ways.

RY: They are critiques on so many levels but I like it that way. But of course if I didn't win the prize I wouldn't have been able to make a project like that because it is so costly.

SB: But I wanted to tie this back into engagement and how you actually work with people in your practice – how you commission and invite interpretations from outside into the space of the art you produce, which essentially intends for a kind of open interpretation. You have said that any kind of improvisation can be political and that everything can be action, but I guess there is a difference between something that is political and something that is able to move or induce an action, or perhaps even alter perception, or how one views the world. A really nice work to think about this is My Last Self-Portrait (2013).

RY: Oh yeah. That's a nice performance.

SB: Maybe you can describe that performance first?

RY: Yes. My Last Self-Portrait is a performance I was invited to do by two curators for a show at the Beirut Exhibition Centre, a very interesting space in downtown Beirut. Somehow some of the intellectuals don't like this space: maybe because it has a relation with Solidere, which is this company that rebuilt downtown Beirut. Anyway, the Centre also shows a lot of modern art from Lebanon from the 1950s and 60s, and these curators invited a lot of artists to do a show about revisiting the Lebanese modern art. Each artist was asked to work around an artist from that period, and I decided to work around an artist called Khalil Salibi, who was basically the founder of Lebanese modern art. He went to the United States to study and then got married to an American woman and came back and lived in Lebanon. This was in the 1910/20s. Then he died. The people from his village killed him.

SB: Why did they kill him?

RY: It was a conflict about the water source but I only realized this after my research – after I had already believed this fantasy about the artist being a victim and that he was killed because he was an artist. I started to fantasize about the idea – that somehow Lebanese society killed the artist. But the thing is that he was actually to blame – he wanted to keep the water for himself so he cut the water supply to the rest of the village and kept it to himself! The villagers actually came from the village to Beirut and killed him there. But I also think they did this because he was from high-class society: he had an American wife in the 1920s in a village in Lebanon. He was always painting her naked and in a way maybe the villagers somehow didn't like. It must have been weird: you had this crazy artist with his naked wife all the time.

SB: And taking all the water.

RY: Yes. And I was interested in this unfinished self-portrait that he painted of himself looking back over his shoulder – the last portrait of himself before he was killed. So for this performance I wanted to turn this portrait into a performance and I asked artists who were starting their careers to paint this picture. I started with three artists but then some other people got excited about the project and other people started painting. I just asked these artists to copy this portrait of the founder of Lebanese art – he is the past and he's looking over his shoulder to the future. He's looking back at the future, somehow.

SB: So what you had was a kind of transmission again: a looping of a loop from then to now, which actually opens up a space to re-imagine and re-interpret not only the past, but how one relates to it…

RY: What was interesting about this performance was that the portraits that these young artists made started out as classical in style, but then over time – because they got bored doing the same thing – they became more crazy and I was interested in this happening. These artists were still learning by copying this master and I was so interested in the time between the future and the past between them. This, for me, is not the present: it's something else.

Raed Yassin was born in Lebanon in 1979 and is a visual artist, curator, and musician (double bass, tapes, turntables and electronic music). Yassin graduated from the Theatre Department of the Institute of Fine Arts in Beirut in 2003 and has exhibited widely, becoming one of the Abraaj Capital Art Prize winners in 2012. In 2009, he was awarded the Fidus Prize for The Best of Sammy Clark at Beirut Art Centre's Exposure.

View Yassin's online presentation of Dropping a Yassin Dynasty Vase, presented as part of Ibraaz Platform 005, here, and an interview with Nat Muller, here.