Interviews

Looping the loop

Amina Menia in conversation with Laura Allsop

The work of Algerian artist Amina Menia attempts interventions into the city - usually the city of Algiers - in ways that underline how history and memory are inscribed into the urban fabric. Working across installation, sculpture, film and photography, her works encourage interaction and exchange and are often rooted in the contested notion of public space, not least because a great many of her proposed works intervening in the city of Algiers, for example, remain unrealised as a result of trying to navigate the city's many-layered bureaucracy. When she does not work in the city itself, she often brings the city into the gallery space, be it with sculptures made of scaffolding, or external window grilles brought inside. In this interview with Laura Allsop, Menia talks about how her unrealised projects have become performative 'meta-works', and how they constitute in her words, an art of the 'unspoken, the invisible, and unreachable'.

Laura Allsop: I'm interested in the notion of reclaiming public space, and how one is able to do so when dealing with city authorities. Many of your EXTRA MUROS projects (a series of urban installations in the city of Algiers, 2005-ongoing) remain unrealised, and I wonder if you could talk to me about the inception of this project and whether all the red tape and bureaucracy you have to deal with on the urban level - the process of actually trying to make it happen - has become a vital part of the work itself?

Amina Menia: When I started my career, I realised very rapidly that I was living in a shift between my practice and my environment, my culture. EXTRA MUROS was a sort of self-questioning and a baptism at the same time. I needed to feel rooted in my homeland Algeria, considering the city of Algiers as a metaphor of myself. Then I had to struggle with the preconceived ideas of the authorities and my peers, who denied this project as an artwork. These reactions overlap with the purpose of my enquiry, which constantly questions the status of public space and forms of appropriation and re-appropriation. When I started EXTRA MUROS, I didn't mean it to be that political. My concern was aesthetic above all. But the bureaucratic marathon became a big part of it. I can say today that these projects are more performances than installation proposals. Struggling in this way and remaining attached to these projects, while keeping the same shape and not compromising them, becomes a performance. And the whole concept of EXTRA MUROS, which was site-specific, became time-specific.

LA: In relation to your work on the Algiers underground, where you proposed visits to the construction sites for the now finally open underground system, it seems the unrealisable nature of your project became somewhat analogous to the long-delayed construction of the underground itself. While of course extremely frustrating, did this analogy nonetheless present itself to you as rather apt, and again, as an interesting aspect of the work?

AM: The Algiers underground was for me a chimera. The very long-delayed construction was an urban legend that I wanted to revisit. After a long time waiting, I wanted to involve the audience in the project, make them participate in the process, reclaim some transparency and some visibility to this construction 'rumour'. But once again, the project couldn't take place, becoming an immediate archive.

LA: You managed to take some photos of the underground system in any case - how you did manage to circumvent the authorities and make a record of this otherwise unrecorded narrative?

AM: When I was preparing each chapter of the project, I was trying to document locations and objects with photos and drawings, thinking very naively that I was simply doing research and sketches. I didn't know that these would constitute the only material 'witness' of my work. In order to take pictures, I had to hide a small camera on my person, so the result was rarely good quality. That's why I decided to make photomontage or collage to express my ideas and concepts. All these are tools to simulate the projects. How to document the unseen? And how to narrate the unrecorded? This is now the real issue of the work.

LA: What about the other chapters of EXTRA MUROS, what state of production are they in? Do you still keep them alive waiting for the possibility of realisation?

AM: It's time to loop the loop, even though I developed a new approach using the suspended spaces and margins of the city, or found urban objects as ready-mades. I am interrogating my own process, questioning the time spent trying to realise them. My projects became an automatic archive. I am now experiencing the opposite method in my work. I will interrogate archives and cartographies in order to conceive my future installations. Thus, I try to evolve my practice from the concept of re-appropriation to restitution, to reconstitution.

LA: I'm very interested in the idea of buildings and spaces arrested in a state of limbo - how do you find these spaces around the city? Do you set out walking and let buildings strike you, or are you looking for particular qualities?

AM: I translate the behaviour and mutations of a society in its public spaces. So while walking in the city, I am always meditating on all the imprints left on its walls, on its streets. Then I always find an urban element, a building that summarises my approach and aesthetic interests.

LA: I wonder if you could talk about the work Undated, 2012, which was included in CHKOUN AHNA in Carthage earlier this year, how you decided on the location and ideas behind this work and how it engages the public?

AM: The concept of the exhibition was very well thought-out. It really tied in well with the political, cultural and economical situation in Tunisia right now. As I know this country well, I chose to do something very interactive. Sharing more than a work, my intent was to involve the audience around the idea of the agora, in a direct reference to ancient Greece, and actually in the location of the ancient Roman forum. The agora was a symbol for gathering, sharing, the freedom of speech, building a common future. I chose to redraw the shape of the forum with support beams, echoing the hundreds of columns still standing all around Carthage. During the opening, I performed a live reading to 'impulse' an activation of the work, so that everyone could read a text, play music, or occupy the place exactly as he or she wanted. It was all about time, history, philosophy. What could a contemporary ruin be? I do regret the fact that I couldn't realise it as I wanted with pink or green fluorescent colours. It was supposed to look more like a 'pièce rapportée', a patch, something added to the site, and not lasting forever.

LA: You use scaffolding a lot in your work, which inevitably suggests temporality, of things being in the process of being built, an adumbration of a building's structure. You have also brought scaffolding inside the gallery, along with 'barreaudages' [grids] - and I wonder if you can tell me how their meanings changes when they were brought inside the space?

AM: I use scaffolding as an alphabet to express my thoughts. They have an exceptional narrative dimension. They reflect perfectly my concerns in issues of time, space, evocation, suggestion. They are the exact metaphor of the suspended, the in-between, the vanishing … they give me flexibility for a relational aesthetic, adapted for each situation. When I use them inside an exhibition space, it's more as a sculpture than a process.

LA: I'm taken by the idea of the unrealised project, be it artistic, architectural or infrastructural. In terms of those projects that are unrealised, I wonder: what are we left with? A Utopian blueprint, a ruin, a trace? At what point does the concept pass into myth, and is this notion of myth something that has resonance in your work?

AM: I am now in a stage where it is a meta-work rather than a work. Now, realising it is a Utopia in itself, it's no longer the initial proposal that counts, but all the extra conditions, I mean non-aesthetic ones that re-shape the proposal. I deal with myth, Utopia, and failure, which become for me romantic topics or concerns. The myth, the trace, the in-between are new ingredients, rooted in another reality I didn't consider in the beginning. It became an art of the unspoken, the invisible, and unreachable.

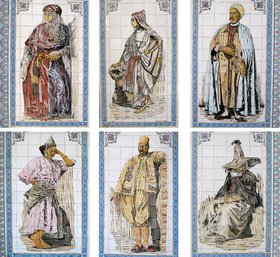

LA: And to extend this, what is the relation of myth to nostalgia, which you explore in your research for the project The Golden Age, which looks at the way we festishise the past (in this case, colonial orientalism, which finds itself celebrated in ceramic frescoes on walls across Algiers)?

AM: I think nostalgia is the most stubborn part of the decolonising process. Once again, I am interrogating an urban element: the ceramic frescoes reproducing the colonial imagery. I noticed that this state of mind imposed itself in the Algerian landscape and in the Algerian artistic scene as well. And I wonder: why do we still consider these images as a representation of ourselves?

LA: In your Chrysanthemums project (2009-2011) a series of photographs, you picture often abandoned commemorative stelae that punctuate the Algerian landscape. Can I ask, were these monuments to people killed during the Civil War, or are they even older? Can you tell me how these monuments function in the landscape, and what exactly do they articulate, or not articulate?

AM: First, I want to say a few words to the effect that Algeria knew a decade of terrorism, not a civil war. The population was held hostage by terrorists, yet never held weapons. This is not a denial, just a historical precision. But back to your question, the only period celebrated and commemorated in my society is the liberation war. It's politically correct to nurture only this memory instead of the others, maintaining amnesia for all other steps of history. In my photographic series Chrysanthemums, I was comparing two types of stelae, commemorative stelae and monuments dedicated to martyrs. The first ones are symbols of promises that are often not honoured.

Monuments for martyrs are justified by an incredible will to take refuge in the past and ceaselessly celebrate the same events and the same period of the Algerian war of independence. This series is also critical of the artistic and ideological 'content' of these public artworks. With these photographs, I wanted to document these public commissions, which are carried by a political or a community project. What is this 'public' art in a country that is badly lacking in democracy? What are the ideological references of an epoch to a region? What is the intention of these popular expressions? I can say that for both Chrysanthemums and The Golden Age, both nostalgia and amnesia are serious symptoms preventing us from moving forwards.

LA: You have worked with Zineb Sedira on preserving the photos of Mohamed Kouaci documenting the Algerian war and I wonder how that project is going and whether you have been able to secure the photos' publication?

AM: Mohamed Kouaci was the only Algerian reporter during the war of independence, so his images are very precious and really tell a lot, because they were images from our side, our camp, when thousands of images made by French army or French reporters were inundating the world. At this stage, there have been a lot of proposals to help archive and preserve this legacy, from academics and from curators. But it's going slowly because the images are not always available, since his widow still wants to keep them 'safely' home.

LA: You are also working with the archive of Jacques Chevallier (mayor of Algiers in the 1950s, who commissioned a series of 'grands ensembles' for social housing in the city) for a film work. Could you talk a bit about this project?

AM: When I found the archive of Chevallier, who was mayor of Algiers during a very sensitive period of Algerian history, I was fascinated and moved. This was the making of an entire part of Algiers, as it still looks today, and these images are totally exclusive. Algerians never saw this period because there is a serious lack of imagery documenting it. In my narration, I'm going back and forth between past and present, relying on the auto-fiction mode. It's like leafing through a very particular family album: the 'Algiers' album, in which small stories become descriptions of the social and historical context. The countdown for the war had already started, so I underline the parallel movements between the two battles: the housing battle (as it was called at that moment) and the battle for liberation, the battle of Algiers. By articulating related concerns, exploring the legacy of the last century's Utopian projects in Algiers, and situated in the fairlure of current-day urbanism, this film looks for the aftermath of the push for modernity in my country.

LA: You're also working on a project for an exhibition in Dublin involving the Paul Landowsky monument to the First World War in Algiers, which has a complex history in that it was encased in a sort of sarcophagus by the artist Mohamed Issiakhem in the 1970s. Recently, a crack appeared in this encasing. I'm intrigued by the idea of 'memory competition' you bring up in relation to this cracked monument, because you wanted to make a resin imprint of the crack but the authorities wouldn't let you and it brought up a lot of issues in terms of commemoration and whether to allow the original monument to become visible again. Could you elaborate on this idea of memory competition, and on how public art inscribes and even prescribes collective memory? Also, how will the monument feature in your work in Dublin?

AM: In both Chrysanthemums and The Golden Age, I have tried to interrogate public art and its visible significant. In those two cases, only the official history is celebrated and illustrated, in only one direction. It is hypnotising the collective memory. In my new research, I try to highlight a memory competition between different visions of the same history. But moreover, and from an aesthetic concern, I lean on the memory nesting manifested and materialised in this double monument: a French sculpture encased in an Algerian 'habit'. Both artworks will feature in my final proposal for an exhibition in Dublin around the theme of 'becoming independent', which will include life-size photography based on one of my key-concepts: the restitution. I'm collecting original postcards, newspapers, and interviews for this body of work. The next step will be comparing and crossing those elements while exploring Dublin's urban landscape and the Irish political and aesthetical stance in post-colonial issues.

LA: Given the difficulty of trying to realise your projects in Algeria, is it fair to say that you find it easier to navigate public space in foreign countries? And if so, how does this irony feed back into your work?

AM: When I work abroad, I enjoy having proper conditions in which to think about and produce art. An already established frame prevents me from wasting time on extra-artistic obstacles. It gives me the distance and elevation to re-evaluate my work in my homeland. It also gives me the courage to refine my problematic and continue resisting.

Amina Menia's work actively questions our relation to architectural and historical spaces. With a preference to site-specific installations, her work appears as an invitation to reevaluate our understanding of heritage, and de-construct our conception of beauty by challenging conventional notions around the exhibition space. Menia has showed her work nationally and internationally, including the Museum of Modern Art (Algiers), Gallery Anne de Villepoix (Paris), Pontevedra Biennale (Spain), Cornerhouse (UK), Museum of Contemporary Art (Leon), and Atelier Visu (Marseille).

Amina Menia is also a participating artist in the Kamel Lazaar Foundation Projects – take a look at her recent work, The Golden Age, here.