Interviews

Hiding Out In My Own Place

Nida Sinnokrot in conversation with Natasha Hoare

What does it mean to be making art within the fulcrum of occupation and amidst precarious state security? Algerian born artist Nida Sinnokrot, currently living in Palestine, has for many years constructed his practice around ways of re-envisioning modes of representation, particularly in cinema and film, and commenting on the ways in which narrative structures are built through image to tell stories about his home nation. In his installations raw materials with diverse registers are brought together to create new and powerful emblematic forms that critique and complexify clichés and shortcuts in critical thinking around, and representation of, the region. In both disrupting and drawing attention to the systemic factors underlying specific social situations in his work, Sinnokrot aims to challenge narrative hegemonies. As a teacher he has witnessed first hand the pressures faced by a new generation of artists in Palestine. His 'back to the land' project seeks to work against the alienating effects of neo-liberalism on this generation and through agricultural work institute new communities.

Natasha Hoare: You grew up in Texas, a remarkable place for a young Arab boy to come of age! How did the experience of dislocation from Palestine form your artistic voice, and how do you negotiate the nationalistic labels that society and the art world assign you?

Nida Sinnokrot: I grew up in Algeria and we moved to Texas in the early 1980s. My parents were Palestinian exile/refugees living in Algeria. When my mother was pregnant with me they flew to the United States to give birth and returned to Algeria a short while later. The French have a term for this: it 'anchor baby'.

Growing up in Algeria was idyllic. We lived in a small bungalow near the beach with a Kabyle village and forest behind us. Nature was my playground. It was very difficult for me to leave and doing so rooted in me a deep sense of nostalgia. I tried to find relief in nature and although there were some similarities, sharing similar latitudes, I remember feeling very small and ill at ease in Texas. Oak trees were so vertical and difficult for my small frame to climb whereas the trees in Algeria had low hanging knobby branches that seemed to pick you up effortlessly. It took a lot of getting used to. I spent most of my time with my head down scanning the ground for similarities and scanning the skies for qualities of light that felt familiar. The smell of sewage took me back instantly. I loved it, but that was rare in Dallas, Texas. The first time I started taking photos I was taking pictures of clouds and close-ups of cracks in the pavement. I was trying to catalogue the similarities between my past and present.

It was a difficult time in the US for minorities and it feels like we are swinging back to that political climate of xenophobia today. It was in the early 80s, Reagan and Thatcher were in power, and terms like 'sand nigger' and 'camel jockey' were used freely by my classmates. When I asked my father what they meant, his advice was to tell people that I was Mexican.

In my undergraduate years at UT Austin, I met some amazing people. They really rescued me from my alienation. We were a diverse group of friends from Mexico, Greece, Ireland, Iran, the USA. We were reading Deleuze and Guattari and watching the films of Tarkovsky and Kusturica and making experimental films of our own. So by nature, it wasn't an identity thing; it was a phenomenon with structures that played across national categories.

The work we were collectively making around immigrant and migrant issues and that period at the University of Texas in Austin was seminal for my development and continues to be. At Bard College, where I got my masters, I did not foreground my background despite the attention around identity politics in art. Identity work was not interesting to me. I was more concerned with the phenomenology of identity formation, the mechanics and politics of storytelling.

NH: Your filmic work pioneers a form of 'horizontal cinema', in which the film is made with the camera at a 90 degree angle, which is righted in modified projectors, albeit retaining the frame lines of the film, whose speed is dictated by the interaction of the audience. You've described this form as an extension of immigrant or diaspora expression, can you expand on this?

NS: That's part of it. That's something I wrote more than 15 years ago to come to terms with my personal experience. I made the first horizontal film loop installation in 1998.

This goes back to the kid who was looking for something in the cracks. I would spend a lot of time taking things apart at home. My fathers watch, the TV, whatever I could. I wasn't always able to put them back together! There was a violence in the process but at the same time it was liberating.

This stayed with me in film school. At Bard, I had an old flatbed Steenbeck 16 millimetre film-editing table and naturally I took it apart. At that point I was reading Paul Virilio and thinking about the politics of the apparatus itself and of narrative structures. I was trying to understand the relationship between colonialism and the camera and trying to liberate the narrative from the cinematic machine.

I was in the film school but spending a great deal of my time in their music department. I was very inspired by Schoenberg, Terry Riley, Pierre Schaeffer. Bob Bileckie, a faculty member, mentored me and it was with his assistance that I was able to realize the first horizontal loop machine.

Traditional cinema creates the world as much as represents it by organizing time and mapping space as rooted in particular registers of Western post-industrial civilization. With horizontal cinema I wanted to create a tool that could shed light on this history and re-imagine the places from which we construct meaning. I believed that if new narrative structures could be invented or old structures resurrected, because diversity in story telling has undergone a drastic extinction, there would be new possibilities for expanding consciousness; for imagining a better future.

The linear logic of editing with one frame following the other was a part of my frustration. My reality wasn't linear. It was fractured like my sense of time and space. Reinventing the apparatus was my way of liberating it and of representing an experience closer to my own.

I was questioning all aspects of the apparatus: why the film ran vertically through a projector rather than horizontally; how to challenge the illusion created by the shutter using its binary regulation of light and darkness; why was there only one projector and why was it bound by 24 frames a second?

Heizenberg understood the power of the gaze on a quantum level and I felt it true of cinema. The pulse of the projectionist, back in the day when projectors were hand-cranked, used to influence the speed of the image. What a wonderful truth! In my horizontal loops, the film reacts to the number of people in the space and their position relative to the images and to one another. The projected images are not bound by traditional 24 frames per second, but they rather move with speeds ranging from 0 to 100 frames per second depending on audience interaction and chance operations.

I would shoot single strips of film about three metres long, and pass them through three projectors so that the images that precede and follow created multiple planes that I think of as the past, present and future, existing simultaneously as a function of speed. From a single film strip an infinite sequence of images emerge as a function of the constantly shifting speed. This alternative grammar reflected my experience, my ruptured realities. Later when I discovered Edward Said describing this as contrapuntal-consciousness I understood it in a larger context.

Cinema produces meaning in its construct of sequential images with beginning, middle and end, illustrating causality while consolidating an imperial gaze, but foregrounding audience participation as the essential locus of the work's logic gives agency that is often overshadowed by the art object. Here, meaning is made quite literally by where one stands and the stakes are high. With every step the film registers thousands of tiny scratches in a process of immediate, arresting decay. This violence is reflected in the machine itself and the relationship between trauma and perception is materialized in its clash of technologies and systems. It's cinema and war. It's the experience of dispossessed and displaced peoples.

NH: We are all working within an art world that is seeking to come to terms with humanitarian disasters such as the ongoing conflict in Syria, escalating hostilities between Israel and Palestine, and the refugee crisis. Within this crisis of conscience the onus seems to be on asking artists how art can cope with these events, and how can representation or indeed abstraction comment, intervene, or even inculcate politically or socially engaged subjectivity in viewers. How do you navigate this environment and how does your work seek to enter into this situation?

NS: I suppose the short answer is by any means necessary. Back in 2001, I was awarded a Rockefeller Media Art fellowship for the work I was doing with horizontal cinema and the idea was to make an installation, in Palestine. I bought my first camera and laptop and began filming myself crossing the Qalandia checkpoint from a hole I cut in my camera bag. During that same period I was researching the aquifers in the West Bank and water scarcity as a way to talk about the situation in the region that didn't fall back on the typical rhetoric of religion, nationalism, terrorism etc. So everyday I would film my walk across the checkpoint on my way to a village that had artesian wells. I happened to end up in the village of Jayyous at the same time that farmers were deciphering confiscation orders issued by the Israeli Army in order to build their wall. There I was with my camera while bulldozers were crawling over the hillside uprooting olive trees and the farmers asking me to tell their story. I couldn't explain to them that I thought the very form of reportage was part of the problem and a select and limited audience in a white cube gallery would see that the work I make far, far away. So I took a detour, and the film I ended up with is called Palestine Blues. I spent years on it, I had no idea it would take so long, and in the end I resolved my artistic conflicts by making a road movie and then fracturing that structure in the editing. By destroying that original structure I ended up with a form that I felt was an honest representation of a road movie in a disappearing landscape. I also had the burden of carrying two audiences. I wanted to make something that would empower the farmers here and still reach audiences in the States and abroad.

My generation grew up with Edward Said and the spirit of the first intifada, with a critique of the media machine and representation. Today, my students are coming of age in a neoliberal bubble. They are far more at risk of falling by the way of the spectacle than I was as an exile/immigrant. Perhaps that's the silver lining of being an immigrant or outsider.

At one level, culture that deals with the surface of crisis, which is all too often, tends to be like a moral laxative, like you go to a museum or watch a reportage and feel overwhelmed by some representation of atrocities and a few hours later your suffering was somehow a contribution, or feel proud to have empathized, or at best, to feel overwhelmed because it's a preaching to the choir situation – yet another spectacle that points to a far more devastating one. Where do you go with that energy? The work needs to point to underlying systems in its use of material and aesthetic choices and that is where abstraction comes in. Abstraction is a vital curative to narrative hegemony. Institutions need to lay similar groundwork in their approach to education and in challenging the dominant discourse.

There is no shortage of culture on our planet but bringing people to it in a way that is meaningful to them is a challenge. One of our greatest priorities is to empower our youth and give them a sense of purpose and belonging, a sense of pride. And you do that by any means necessary. Right now I'm working on a 'back to the land' initiative that I consider an integral part of my art practice and one of its prime objectives is to bring youth together and give them a sense of self though farming, recycling, collective decision making, among other things, as a way to combat the increasing alienation I witness in our increasingly neoliberal, individualistic society. Picking up a plough can be far more threatening than picking up a camera or a weapon for that matter, it seems.

NH: We showed Rubber Coated All Stars – assemblages of rubble, stone, discarded balls and lashings collected in Jerusalem, in which rocks are essentially wrapped in rubber, each balanced on a metal stand that sit on a white pedestal – at Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art as part of the exhibition Art In the Age Of…Asymmetrical Warfare. The work mediates on the material reality of violence and its mediation, manipulation, and circulation. As an artist, how do you avoid your work becoming part of the ever accelerating exchange of image surrounding the concerns of the region, do you see your role as being predicated on disrupting this flow, or highlighting its process and underlying structures?

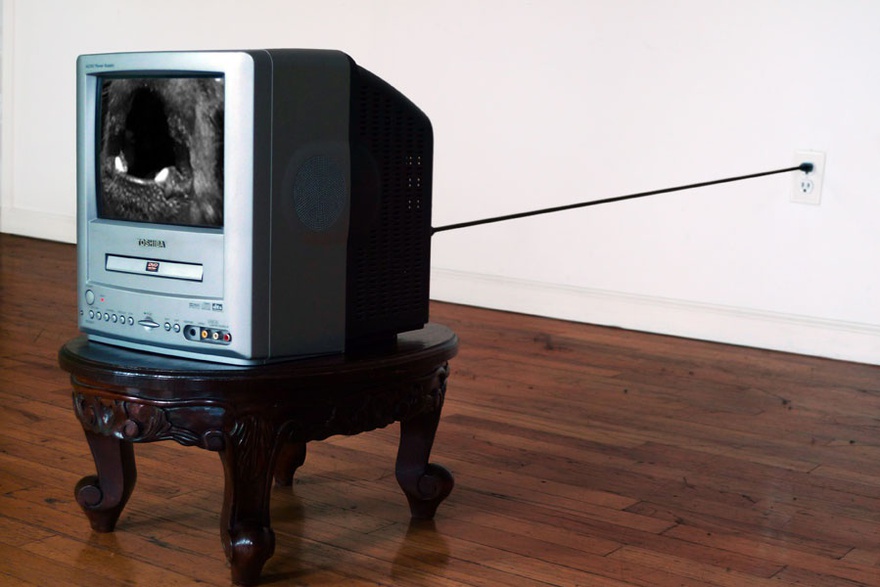

NS: I swing between both disruption and exposing the underlying structures and that depends on the work. At one point, when I was in the Whitney Independent Study programme in New York during 9/11, I became desperately frustrated with technology and image making. That was a period of great frustration. I made a piece called Untitled Shutter which is essentially the shutter from a very large old land camera nailed into the corner of a room, with a light bulb in front of it on the floor. When approached, the shutter opens with a sharp, loud snap, triggering a visceral and conceptual shock. With the simultaneous flash of the light bulb, the corner behind the shutter is activated; a phantom house with an upside down heart resting squarely in the center of the roof appears as a shadow, instantly disappearing and re-appearing in relation to the viewer's movements. There is no image, only the making of its disappearance. But I also made Barking Dog, which is a very angry work comprised of a TV monitor and a baroque carved footstool. The monitor sits on top of the stool playing a video loop of a barking dog in extreme close up and the whole thing is plugged into a wall outlet but the cable is so stretched that it feels like that power cord is the only thing keeping that dog from tearing you up. Al-Jaz/CNN came from that same time and again it pointed to the power structure of networks. It was simply two televisions plugged into the same power outlet with one playing CNN and the other Al-Jazeera, both live. I think that was the last image piece I made for a long time.

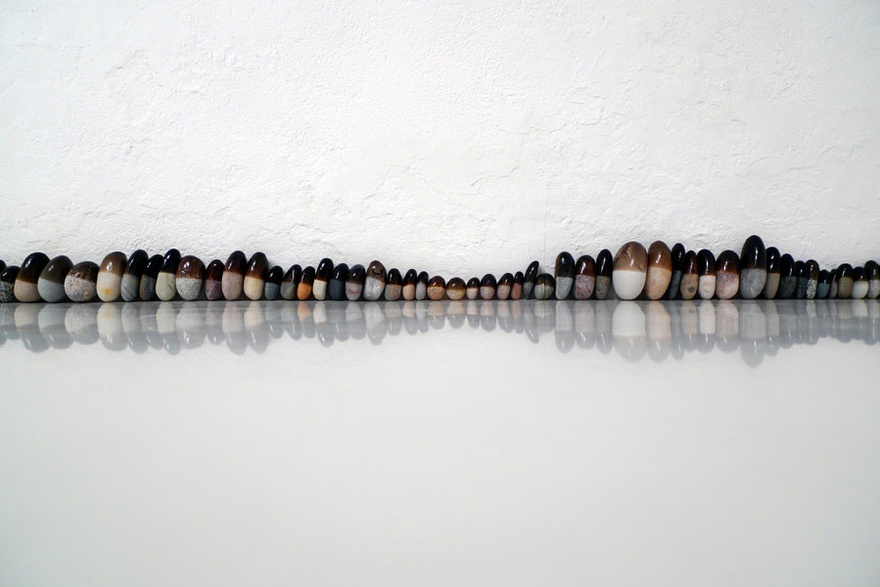

In fact, the next work I made was Rubber Coated Rocks. Stone and rubber, very basic in material composition, nature and man-made, and of course they recalled rubber coated bullets but their potential energy is tempered by their anamorphic preciousness. With the All Star series I showed at Witte de With, they became larger, less refined and more abstract. These are essentially made of garbage and rubble, discarded scraps and lashings collected around Jerusalem. They are dirty and some of them have distinct odors, the antithesis of finely crafted works of art. Their aestheticization happens in the height at which they are perceived, precariously balanced on steel stands atop pedestals the tension in their suspension is palpable as if arrested a split second before impact. The portraits have them one further step elevated, isolated and stylized in a process that references the production of martyrdom, like the children in my neighborhood who are invisible until they pick up a stone and in the event of their death, get their portraits photo-shopped and circulated on posters. So in some sense it captures this recurring swing between pop and social realism and like with the horizontal cinema work, point to the machine or mechanisms behind the image.

We tend to be highly sensitive to the production and circulation of images in their representation of the Middle East abroad but we need to be equally concerned about how we image and imagine ourselves here. In the West Bank today the mortgage industry is the major circulator of images that are designed to capture the local imagination. How do you demonize a people is one thing but also how do you tame them, how do you make them indebted to authority? Those are some of the things I tried to deal with in my recent solo, Caravans, at Darat al Funun in Amman, Jordan. Those images are there... in the bible for example as is the case in my work Jonah's Whale, so it's not that we should always avoid playing with them but we should know where they come from!

NH: There has been a preponderance towards the nation or region orientated exhibition in contemporary art as a mean for providing visibility to artists from underrepresented non-western geographies. How do you feel to be curated into shows that operate in this way? Can in be damaging to have your practice ostensibly labeled geographically? Or is it a necessary, if rather heavy-handed, form?

NS: This reminds me of the first time I met a gallerist. He loved my work... went on and on about it for quite some time but in the end he said: 'Nida, I can't sell you as a Palestinian artist because you have an American passport and I can't sell you as an American because you are an Arab'.

Once we accept these geographic categories we are in enemy terrain; Edward Said's life's work was to reject these premises. These are imperial terms used to organize the world and since the end of Cold War we hear MENA not Mediterranean. These are political constructions and are incoherent when considered geographically, yet we all know what they mean. Of course, there are regional shows that handle the topic thoughtfully, questioning and challenging these definitions. In fact, I don't know any curators that do not take these things into consideration today.

NH: Where would you position your practice within this consideration?

NS: I may draw from my local experience, but I'm not making work that is regionally specific. Framing work this way runs the risk if it being exotic and valid for that alone. I think of a few of my younger students and their tendency to simplify the issues they are struggling with by using the same didactic narrative structures that I was talking about earlier. Somehow they are far more attuned to the dictates of the market than I ever was at their age, or now for that matter. There is a tacit understanding that if a student makes work about the veil for example, it has a high chance of getting noticed. This disappoints me because the issues that need to be dealt with are not so much the social, religious symbol but the industry around it and that is not regionally specific. There is always need for work that broadens the conversation – for work that is able to conflate regional divides.

The struggles we face are not specific to our regions. For example, farmer's plights at the annexation of their lands in Palestine can be looked at with the same analytics you might use to understand farmers from the Yangtze River Valley being uprooted for the construction of a hydroelectric dam. Extremism has no prejudice and has its roots in the same machine that effects extremism in the weather, petro-dollar exploitation, our wars, our warming, our colonial structures. These are all OUR issues. You don't have to look far to see the effects of poverty, exploitation, colonialism, and trauma. Chances are these are happening in a neighborhood not too far from you. It's a shame one has to go to a museum to empathize.

NH: The narrative of migration has taken centre stage in current affairs and world politics recently, with debates as to the status of migrant versus refugee, and borders, which were somewhat permeable becoming increasingly closed. In this climate is there a counter narrative of 'staying' that we can observer in some cultural actors? What are the politics of remaining, or indeed of leaving?

NS: I don't know that there is a counter narrative to migration. Not criminalizing it, not conflating it with terrorism would be the first step. What we are seeing is only a dress rehearsal for what is to come with the specter of climate refugees on the horizon.

Staying or leaving; who has the choice? It depends who you are talking about. Are you inside or outside the system? More often than not, the refugee has no choice but to leave as a matter of survival. Staying is criminalized, leaving is criminalized. So this phase of the crisis like the ones that are sure to follow have to challenge the qualifications nation states have in place to give people the right to choose one or the other. Right now, staying and leaving...it's a situation, not one or another. You stay and leave at the same time...it's like in Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath when Tom Joad, hiding from the authorities mutters to himself in disbelief, 'if anybody ever told me I'd be hiding out in my own place...'.

Borders are language. It's going to take a lot of work to dispel the lazy hegemonic rhetoric of fear, and foster compassion. This is the work of culture, and the immigrant is the vanguard.

Nida Sinnokrot (1971, USA) is a filmmaker and an installation artist, who lives and works in Jerusalem. His work is very reflective of his hybrid identity and personal experience. Of Palestinian origin, Sinnokrot grew up in Algeria and moved to the United States as a teenager. His films, installations, and sculptures increasingly explore the traumas generated by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. After earning a BS in film, television, and radio from the University of Texas, Austin, and a master of fine arts in video and cinema from Bard College, New York, he then participated in the Whitney Museum Independent Studio Program. Palestinian Blues, his first film, has won numerous awards in international film festivals. Sinnokrot's work has been included in various international exhibitions, including Bozar in Brussels, Old City Jerusalem (Jerusalem Show), Artists Space in New York (When Artists Say We), and the Kunsthalle Exnergasse in Vienna. In 2009 Sinnokrot also participated in the 9th Sharjah Biennale.