Interviews

A Fraction of Experience

Omar Robert Hamilton in conversation with Elisabeth Jaquette

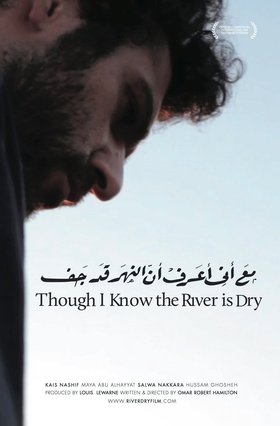

Omar Robert Hamilton, an independent filmmaker based in Cairo, is the producer of the annual Palestine Festival of Literature and a founding member of Mosireen, a media collective born out of the wave of citizen journalism in Egypt during The Egyptian Revolution of 2011. Though I Know the River Is Dry (2013) is his third fiction short film, an independent, crowd-sourced work, it weaves together familiar themes of Palestine: the division of families, it considers therole of the past and the notion of return. Evocative, elegant visuals are guided by the main character's voiceover narration, an intimate soliloquy of regret for the choices that brought him to leave his country and resolve in his return. Scenes of Palestine are punctuated by judicious use of archival footage; the past emerges as something both stitched into the present and to be weighed against the future. In this interview, Hamilton discusses his latest short film, finding a balance between art and activism.

Elisabeth Jaquette: In addition to being a beautiful short film, Though I Know the River Is Dry is built on strong photographic and literary sensibilities, enriched by usage of the archive. How did the film take on this particular shape?

Omar Robert Hamilton: A lesson I learned in Maydoum (2010), my last fiction film, was that we wrote a script that was really more like a short story than a film. In Though I Know the River Is Dry, our intention was to take all the different tools that cinema gives you, and to find a form that allows you to use as many kinds of weapons as there are to be used. That's why we used a voiceover and this structure in particular, which gave a real freedom to do whatever we wanted in a way. The film came out very close to what the script was. I don't know if that's usual or unusual, but for me it's a bit unusual. In the end the film was better than the script, which is important. Maydoum's script was better than the film – it was very straightforward, just a learning thing out of film school, and the script had more layers in it than the film ultimately could carry. Though I Know the River Is Dry was written in a very spare fashion, not putting in too much. We wrote a script that only had the things we knew you would be able to see, which then pushes us to realize it.

EJ: How did the project begin?

ORH: I had always wanted to do a short in Palestine. At first, I started writing a horror story set in Hebron; it was going to be a real genre kind of thing. But I decided against that. This particular story started in 2010, really. I was trying to write a poem about Qalandia, because I thought there was something that nothing except for a poem could capture about it. The poem eventually evolved into the sequence at the end of the film with the voiceover, but it was also the starting point [for the film]. I had wanted to do something with Qalandia as a centerpiece because I always found going through the checkpoint so emotionally devastating. In practical terms it was a location, and it was there, and it was built. So the question was: how do you get in there and capture a bit of what that felt to you? I had a general feeling about needing to do something about Qalandia, and the rest of it grew around the journey.

EJ: Why Qalandia instead of other checkpoints you had been through?

ORH: It's the mechanization of Qalandia. The experience is almost less humiliating if you have soldiers who are standing there that at the least – at the very least – you can stare at them with hatred, and at the most you can square up to them. But Qalandia is a very carefully thought out system of bars, and locks, and sounds. There is something particularly inhumane about it that always made me super pissed off whenever I went through it, to the point of tears, a couple times. It's so much more thought out than the other checkpoints, so much more designed to make you feel small and powerless.

EJ: There is a scene in the film where the main character takes his fist and strikes it against the railings as he walks out of Qalandia. There are so many beautiful, split-second images in the film – sparrows fluttering over razorwire, a plastic bag floating over the wall – and this is one of them, this contained rage against something that is so mechanical, unyielding and impersonal.

ORH: That was a great-improvised moment. We were stood there, the actor came out punching the bars, and we were lucky that we managed to run and catch it.

EJ: What was it like filming in the checkpoint?

ORH: It was surprisingly not as hard as we thought it was going to be. We were really nervous about it and had a very set plan about how to get in and out in twenty minutes: who was going to be where and what the protocols were. When we were in there, we realized the soldiers had to really care in order to do something. They had to want to stop you. After about 45 minutes they started shouting at us over the machines, saying 'What are you filming, what are you filming?' But they would have had to come out in uniform and in formation to come out to the side we were on and they were too lazy, I guess. Whoever was on duty that day just didn't care. After they started shouting at us over the loudspeakers we sped it up. Overall, we had about an hour and a half of filming in there, all in one go, which is much more than we had banked on.

EJ: What had you expected them to do? I'm sure you had contingency plans.

ORH: We had expected them to come out and stop us quickly, because they know about cameras and they know in general that they don't like people filming what they do. But maybe this is another problem: that Qalandia is so blatant, and so obvious, and thousands of people go through it every day, that they're not even embarrassed by it anymore.

EJ: You postponed the filming during the first year of the revolution in Egypt (2011). How do you think the gap of a year influenced the film? Obviously the world changed in those months as well.

ORH: The script had to change dramatically after the revolution. The 2010 script was all about how someone can be driven to the point of having to leave, and it ends with him leaving. Then the revolution happened and that was no longer the way one thinks about the world, so the whole thing had to be shifted around to become what it is now, which is much more about the inevitability of resistance.

EJ: In some respects the film reads in almost a literary way, woven with literary and biblical references that you found a mannerto integrate both in the voiceover and visually. There is a scene where the main character lifts a copy of the novel Season of Migration to the North, by Tayeb Salih, out of a box, before replacing it again. Season of Migration to the North is the iconic, canonical novel exploring what it means to leave one's region and travel to 'the West', and what it means to return after that. There is a rich Palestinian literary tradition that deals with many of the same themes the film does: weighing the past against the future, stories like Return to Haifa by Ghassan Kanafani or novels I Saw Ramallah by Mourid Barghouti. Why Season of Migration to the North?

ORH: Season of Migration to the North is part of a general tradition of looking westward or northward that has changed, and what we're saying has changed. It's a signal that this - the book and what it represents – is something that has been left behind. The book is still important and it's still a big signifier, but we're looking southward or eastward now. Beyond this, the idea of going and coming – or the inability to go or come – is an entire undercurrent in the Palestinian experience and an intensely rich theme. I personally went through a fundamental shift in terms of this idea – I came to Egypt from England and stayed, and I am staying. I feel like that's happening to a lot of people all over the place. If people are no longer thinking that you have to go north or west to make things happen, that's a key shift. If we can sustain it, it's incredibly important and it's the foundation for the future.

EJ: How do you see Though I Know the River Is Dry in relation to the other projects you're working on: the Palestinian Festival of Literature and Mosireen. Many artists in Egypt have split their practice since the revolution, engaging in some political projects and some that are completely apolitical. In Doa Aly's essay 'No Time For Art' she wonders if there is a place for art during the time of revolution, writing: "There's something morbidly bourgeois about implying the existence of a 'time for art.' The thought that art can only exist to react is disquieting. But more so is the idea that art cannot exist if it cannot react "appropriately". Did art ever exist or was it passing time waiting for the revolution?" She wrote this in June 2011, months after the beginning of the revolution. But I feel many artists here are still weighing the same dilemma: how do we justify artistic projects when politics are so imminent?

ORH: I feel the same, and I think that this is why this film had to be postponed for a year. The 18 days [from 25th January 2011 to when Mubarak fell in 2011] were different, everyone was just there and that was it. It didn't take much political commitment to be there, it was just an inevitable fact that you had to be. So the commitment only really came afterwards, when you work out what it is you can do to be useful. After Mubarak fell I had to travel to Washington DC for work, and then to Palestine to prep the film. But reading the news from DC doesn't make you understand that it's the same revolution that's still happening. It was when I came back to Cairo in June that I realized the extent to which the revolution was an ongoing thing. I was unfortunate not to have my camera with me on 28th June, so I got to throw some rocks at the police, and it became my chance to really get involved. I started working with Mosireen and doing Tahrir Cinema. Once I felt I was doing things that were having an impact, or being effective in some way, was when the art firmly took a mental back seat. The film was pushed back, and it was all politics. After a year it became clear that the revolution will go on, and if you're going to be able to fully commit to it for let's say ten years, you also have to maintain the other side of your life - the more in-depth work. As great as the five-minute videos are, they're not challenging all the time. In the end you have to find a way to do the things that are short term effective and to do the things that are long term effective.

EJ: What do you think film should strive for in terms of responding to the political?

ORH: For many films, when you read interviews by the people who are making them they say 'We hope this film will make people interested in our subject, or ask questions about it, or find out more.' I think that's not enough. We shouldn't behave as if we have a passive audience we want to enlighten. In Though I Know the River Is Dry, we were trying to recreate a fraction of an experience, a Palestinian experience. Not just an individual experience, but also a collective experience and a historical experience. Partly what you want to do is to recreate what something feels like, whether that is injustice or humiliation or grief. We're trying not to be didactic; it's not a film that's giving you a history lesson or trying to tell you facts, because you could go on Wikipedia and find everything out in five minutes. If people wanted to know what was happening in Palestine, and if that would make them care, then that would have happened a very long time ago. Partly what we're trying to do with the structure and the archive in Though I Know the River Is Dry is to allow people to make their own associations about what they're seeing. You can push that a lot further, you can edit it in a more abstract way than we did in the end. There was actually much more global content in our original script, footage from the Bosnian war and the Egyptian revolution that gave it a more global association. In the end the film ended up more localised.

EJ: I think that is part of what makes Though I Know the River Is Dry so effective as a short film. It doesn't try to tell the story of Palestine from beginning to end in a narrative way; instead it's an extremely intimate slice of an existence. You see enough for it to be compelling, but there are questions left unanswered as well.

ORH: That's key, the balance between giving the viewer enough to care about this person. On the one hand we're stuck as humans in wanting to relate to people in a personal way. And so to make a political film you have to hook it on to a personal experience of some kind. But it's not really about this person; in the end this person is irrelevant. So you try to create a film or structure that gives the viewer a broad political experience in an emotional way, going through an individual but while trying to be not about that individual.

EJ: What then were you hoping for out of this film?

ORH: The question of what you are hoping for comes up against the question of what you can do in a short film. If it was a long film and we were going to the cinemas you would hope that everyone is going to see it and it's going to be a watermark moment in the global perception of the Palestinian struggle. But you don't have those expectations for a short film. You just do the best thing you can and hope you can raise the money to make the next film that's longer and can play in every theater in the world. What you're hoping for is that you've not been a parachute filmmaker going and making a film and leaving and that your friends in Palestine think you've done something that they would have done. And that's key. But this is another part of coming and going. None of us in Egypt have been able to make anything about Egypt in the past two years because we're all stuck in it. And I imagine it's the same if you've lived in Palestine your whole life. I'm in a very fortunate position of being able to come in and go out and have and the distance it takes to create a script. And it does, it takes physical distance. And even if you can't get the physical distance there's a level of temporal distance you can achieve. Six months ago if I thought about the future I would think about a week, whereas now if I think about the future I think about a month or two months and maybe even six months. But these things are getting back to normal. I can sit at home for a day now, and read for the morning and do a little bit of work in the afternoon and not feel like I've just betrayed my country.

Though I Know the River Is Dry premiered at the International Film Festival in Rotterdam, where it won the festival nomination for Best Short Film at the 2013 European Film Awards. Judges commended it for the "remarkable way it connects contemporary political issues with emotional dilemmas," and that "in a particularly undogmatic manner, it offers multiple readings, while simultaneously sharply addressing historical, political and economical realities."

Omar Robert Hamilton is an independent filmmaker, producer of the Palestine Festival of Literature and a founding member of the Mosireen Collective in Cairo. Since 2011 he has made dozens of short documentaries on The Egyptian Revolution which begun in 2011, helping to make Mosireen the most watched non-profit YouTube channel in Egypt of all time. His third fiction short, Though I Know the River is Dry, premiered in competition at Rotterdam where it won the Prix UIP and is currently nominated for Best Short Film at the 2013 European Film Awards. His films have appeared on the BBC, Al Jazeera and ONTV; his articles in the Guardian, the BBC and Jadaliyya; and his photographs in the Guardian, The Economist, al Shorouq and the Daily Beast.