Interviews

On Building Nations

A two-part conversation with Szabolcs KissPál and Mahmoud Khaled

Szabolcs KissPál and Mahmoud Khaled's exhibition On Building Nations (August 19–October 23, 2016), was the result of Edith-Russ-Haus' annual production-oriented grant, provided by the Foundation of Lower Saxony, which enables the realization of three projects per year through an open-call process. Grants are allocated by an international jury that includes the curators at Edith-Russ Haus, and for this particular grant, as directors of the Edith-Russ-Haus, Edit Molnár & Marcel Schwierin, explain, 'the judges immediately saw the possibility of staging a full double exhibition primarily based on the plans [KissPál and Khaled] had included in their applications,' thus leading to 'a unique collaboration.' This two-part conversation allows for the regional specificities of each project to be critically addressed, whilst bridging the works of both prizewinners. Szabolcs KissPál speaks to Edit András, an art historian with a research focus on Central and Eastern Europe and Russia; and Mahmoud Khaled speaks to Alexandria-based Egyptian political sociologist, Amro Ali.

I. On Building Nations: Budapest, Hungary

Szabolcs KissPál in conversation with Edit András

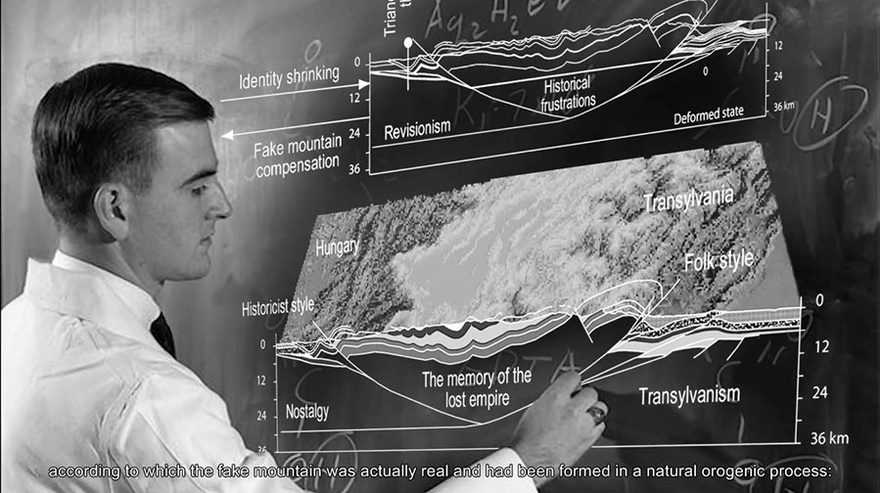

Szabolcs KissPál is an artist based in Budapest, Hungary. His research-based project From Fake Mountains to Faith (Hungarian trilogy) was started in 2012, and completed in 2015–16 through the support of Stiftung Niedersachsen and Edith Russ Haus Für Medienkunst – Oldenburg. The body of work, consisting of three parts, applies the method of docu-fiction, to investigate the anatomy and genealogy of the authoritarian 'illiberal' Hungarian State policy, by revealing the cultural philosophy that underpins its ideological basis. Composed of two large format narrative docu-fiction videos, the first 16 minute instalment titled Amorous Geography (2012–16), analyses the symbolism of an 'ethnic landscape' as an ideology-driven political geography in the context of European colonial objectification of ethnicity and race.

For the second 19-minute video, The Rise of the Fallen Feather (2016), KissPál introduces the viewers to the romantic historiography of national myths and their origins, dealing with one of the most persistent – though repressed – motif of the Hungarian historical memory: the trauma caused by the Trianon peace Treaty (1920) which together with the Hungarian Holocaust (1941–45) has had a long lasting effect on the development of the Hungarian society.

The third and final part, is a museum-like presentation of a fictitious archeological find, titled The Chasm Records (2016), which, through a collection of historical objects, establishes interconnections in a larger historical and cultural framework describing the 'turanism' – an ideology and neo-pagan worship as a reemerging form of political religiosity. The collection itself contains 70 genuine (and partly manipulated) objects, each with entry-like descriptions, along with 46 printed (pages and 10 video documents contextualizing the items. The project premiered in August 2016 in Oldenburg.

Edit András: In Hungary, the Trianon Peace Treaty following WWI – which resulted in a significant territorial shrinkage of the country and in the dislocation of huge portion of its population – is still treated near 100 years after as a decisive national trauma that is the core of national identity (at least how it is communicated by the regime), overwriting all other traumas among them the country's involvement in the Holocaust. As it is appropriated and strongly represented by the official politics of the recent regime, and is understood as the measurement of one's patriotism, progressive artists detach themselves from it. You are the only one addressing Trianon in your art making practice. Why do you find this topic relevant for a contemporary artist and what is your position?

Szabolcs KissPál: Let me point out, that even though the Trianon Peace Treaty is specific to Hungary, its timely discussion within society, evidenced by the official Hungarian political rhetoric, reveals an increasing global trend of a new nationalism emerging worldwide since 2010. This was the exact year the nationalist-conservative party led by Viktor Orbán came into power. The emergence of the same forces occurred globally from Russia to the US, from Turkey to the post-Brexit Britain. All these ideological patterns rely on the concept of unity at a price of exclusion, which converges eventually in a 'conservative revolution', and ultimately leads towards a new 'fascist internationale'. The statement of the World National-Conservative Movement (a Russian political initiative aiming at creating an international alliance of the extreme right) mentions that the 'Victory of the conservative revolution even in one country without fail will provide an example for other countries.'[1] Viktor Orbán's Hungary might take up this role with success. The slogan 'Make _ _ _ _ _ great again!' – in which one can substitute almost any country name by now – became generally applicable, and in all the instances is grounded in the mythical idea of a former greatness, a nationally uniform, idyllic Golden Age, undisturbed by 'the other' which needs to be reinstalled through division, separation, exclusion.

The Trianon-phenomenon therefore constitutes a globally relevant case study. As these populist rhetoric appropriates and diverts the historical past, I felt the need to re-appropriate the historical narrative and the necessity of creating a counter-mythology – two tasks for which contemporary art has both legitimacy and the critical tools to tackle this highly politicized subject matter.

Szabolcs KissPál

From Fake Mountains to Faith (Hungarian Trilogy), 2016. 'Intro'

HD video, 3 mins 30 secs.

EA: What is the reason for your personal interest in this subject matter, and where does this "unique" artistic obsession come from?

SZK: On a personal level, my special interest in the topic is due to my background: I was born and raised in Transylvania, Romania, a multi-ethnic region which was one of the largest territories detached from Hungary as a result of the Trianon Treaty in 1920. Even though I resettled in Hungary more than 20 years ago, my migrant perspective differs from the consensual 'inland' Hungarian interpretation of the event and its aftermath. As a member of the Hungarian speaking ethnic minority of Romania, I had the chance not only to experience the rather complex inter-ethnic historical reception of the event, but I also had to personally experience the objectification and instrumentalization of my own national identity by the nostalgically paternalistic nationalism of the Hungarian political attitude. This made me very sensitive and critical on the issues of identity formation in general, and primarily the construction of national identity.

EA: Trianon is a sacred, untouchable issue not just for the court historians constructing the official narrative or affirming the narrative dictated by the state, but for any historian dealing with the period. Thus, any kind of fictionalization or critique is unacceptable and conceived as blasphemy and close to treason. Your work breaks the taboo doubly; you touch it, and you fictionalize it since the genre of you work is a fictional museum filled with docu-fiction items, objects, photos, videos etc. Your position could be conceived as a very strong statement against the official narrative, but how can criticism work through this media?

SZK: My drive to engage with the issue came directly from the fact of it being a socio-historical taboo, which begs for an artistic intervention. As the topic has been continuously fictionalized both by official and popular historiography I have chosen the method of counter-fictionalization because it is the most effective way I was able to approach the reading of the subject. And so, by subversively diverting its interpretation, it offers the potential to deconstruct the myth from within. According to Karl Marx the great world historic facts appear twice in history, first time as a tragedy, the second time as a farce.[2] By embedding just a few fictional elements in an otherwise historically accurate narrative, I am not aiming at the revelation of historical possibilities and parallelsbut on revealing the manipulation of history from the present as a farce. This is where the criticism of the project is anchored.

EA: You walk on thin ice. The docu-fiction works so perfectly in this case, that even a visitor with vast knowledge about Trianon could be lost and be embarrassed as to which elements are "true" and which are imagined. The imagined elements are mostly congruent with the violent readymade and found images and context, so the visitor is confronted with a huge dose of collective mourning and hallucination as well as the visualization of aggression and desire for revenge. Don't you recognize the danger of the method of "overidentification", understood as an affirmative project that an irredentist, nationalist visitor can easily identify with? How can you prevent this interpretation? Do you think this method, that was very popular in the nineties, is still relevant and can still work in our harsh and turbulent times? And if so, in which way could your critical position and message be pushed through?

SZK: The power of docu-fictional narrative comes from the authority provided by the documentary elements, which foregrounds factual detail for the subject of the narration, and thus imbues the fictional elements with the necessary attentiveness that factual evidence demands. I don't see the possibility of over-identification as a danger and I don't think the interpretations eventually arising from such a position should be prevented either. On the contrary, I hope that this might contribute to the involvement of those who share a nationalistic perspective, and hose position is here criticized.

As for the actual relevance of such a methodology: besides the more active and present oriented interventionist strategies – which I also apply in my other artistic projects – the method of fictionalizing history functions not only as a cognitive tool to the present, but also as an act of reclaiming access to the past, and through that, to identity politics. In this sense I consider it relevant, while its efficiency is partly limited by the 'classical' conditions of an artwork within an art context. The docu-fiction in the form of moving images has however broader possibilities to subversively spread and carry the message. I believe nonetheless, that one of the most important challenges of contemporary art besides the direct, unmediated interventions in the socio-political present – which part of my practice deals with – is the re-appropriation and reinterpretation of the historical past, in order to deconstruct the populist historical narratives.

EA: The issue of Trianon is artificially kept alive and is relevant in Central Europe. In Hungary, it is not yet relegated into history but is a burning political issue, and as such, used and abused for political purposes, covering historical responsibilities and substituting social obligations and problem solving. In the neighbouring countries with large Hungarian minorities it generates tension and disturbs the status quo even if only on a mental level. However, could it be interesting or relevant for a non-local or non-regional audience that is not familiar with the issue? How could it speak or convey a pertinent message to the art world of the Global South?

SZK: Dealing with a topic so rooted in the national history will always raise concerns of the possibility and efficiency of cultural translation, and as such, is always constrained within limits. The translation of the message is further limited by the importance of Hungary as a small and less significant actor of the global geo-political landscape. At the same time, the anatomy of the process in which the new nationalism is being constructed in an illiberal environment might be of importance for the Western countries, as very similar political processes are underway in their societies. In the past few years growing attention has manifested in the political ideology of the Hungarian government in the international media, looking at the transformations as a laboratory process where liberal democracy is being brought to an end.

EA: The post-colonial discourse is widely acknowledged outside of academia and is prevalent in artistic practices, however, this is not the case with the post-socialist condition; as such there seems to be an absence of discourse on, and visibility of, artists addressing this issue. Although there is a considerable interest towards nationalism in the East-Central European region, it does not take into consideration the diverse historical path, since the phenomenon of post-socialist nationalism is not widely analysed and theorized. How do you see this imbalance between the two positions, and do you see any overlap between them?

SZK: I am not sure about the whole East-Central European region, but in the case of Hungary there is a frustrating contradiction in how colonialism is being interpreted. On one hand – because of its geopolitical location, there is a tradition of self-victimization given the history of colonialisation by the Ottoman, Habsburg or Soviet-Russian Empire. In the present this frustration has been transferred and reformulated in the context of the EU, in both the official political rhetoric and the one of the far right who often refer to the slogan 'We won't be your colony!' – a phrase widely used by Eurosceptic forces. Furthermore, the lack of constructive Hungarian participation in finding joint European solutions on the recent migration crisis wasjustified by Viktor Orbán himself, with the argumentation, that as the crisis is a late effect of colonialism, 'in fact it is not our problem.'

Meanwhile, there is a partly unconscious manifestation of a pseudo-colonial fantasy targeting the region, the fetishistic symbol which is the pre-Trianon Greater Hungary. The major object of this fantasy is the possession and control of the geo-ethnic space of the former Hungarian Kingdom, a manifestation of a both political and cultural colonialism with its specific arguments, institutions and political interventions. The populist rhetoric addressing the issue is one of the most important constitutive parts of the construction process of new nationalism. Nevertheless, the pseudo-colonial self-positioning of the post-Trianon Hungary within the Central European region, especially the instrumentalization of ethnicity might be of interest for the art world of the Global South as well.

Szabolcs KissPál (Marosvásárhely, 1967) lives in Budapest, Hungary. His main field of interest is the intersection of new media, visual arts and social issues. He has been also teaching at various universities in Romania, Slovakia, Germany, and is currently working as assistant professor at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, Budapest (Intermedia Dpt).

His works have been presented at the Venice Biennial, Kunsthalle Budapest, ISCP and Apexart New York, Stedelijk Museum, Seoul International Media Art Biennale, and other venues, and are part of the collections, such as the Ludwig Museum for Contemporary Art, Budapest, Ostrobothnian Museum Vaasa (FIN), Museum of Contemporary Art Bucharest (RO), Paks Collection (HU), Kadist Art Foundation Paris (FR), Muzeum Współczesne Wrocłav (PL). He was recipient of various grants and scholarships (Munkácsy Prize, ISCP New York, Kulturkontakt Austria, Stipendium für Medienkunst am Edith Russ Haus, Stiftung Niedersachsen).

Between 2012–2015 he has been actively involved in various activist projects including museum occupations and civil disobedience actions.

II. On Nation Building: Alexandria, Egypt.

Mahmoud Khaled in conversation with Amro Ali

I have been familiar with Mahmoud Khaled's artistic works for a number of years, and his creative output never fails to astound the observer. Alexandria, the city we both herald from, can often be a political tempest and urban dystopia that deepens a chronic melancholia within the public realm. This, in turn, foments nostalgia through the citizenry who long to live in a sepia-tinged so-called golden age. What romance is to Paris and ambition is to New York, nostalgia is to Alexandria. Yet perhaps because the city functions in a world of intangibles, one where the mythologized metropolis is drowned in a long glorious history that torments the human imagination; will as a result, ruthlessly press the artist, poet, writer, and thinker against established boundaries; at times breaking them.

Political theorist Fredric Jameson noted that nostalgia is an 'alarming and pathological symptom' of a modern world unable or unwilling to engage in any meaningful way with its own historicity. This is where Khaled's work comes in: he seeks to engage this symptom by confronting the Alexandrian spectre of memory. His latest work A New Commission for an Old State (2016) propels the progenitor of nostalgia, memory, into a new site-specific exhibition. A form of commemoration that embodies complex narratives in the young artist's new body of work, through three iconic artefacts within the Egyptian context.

The first is a gated summer resort in Alexandria called Maamoura built by the state shortly after Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power to accommodate the new elite of the 'rebranded' (post-1952) Egypt. The second is a landmark text titled Maamoura's Victims written by Judge Hassan Jalal who was a harsh critic of the Egyptian monarchy. The third artefact is a 1961 film by Youssef Chahine titled A Man in My Life, which started production in Maamoura a few months after it officially opened in 1959. The story revolves around the life of a fictitious architect who is known for his remarkable modernist style and who has built one of Maamoura's most memorable buildings, which is used as a backdrop in the opening scene of the film.

Amro Ali: Your recent solo exhibition in Germany last summer is highly fascinating and it certainly overlaps with my work in political sociology. The driving question that intrigues me is: Where does Alexandria, as an autonomous entity, fit in the artistic narrative that you have developed? My understanding of Nasser-era rebranding has more to do with how Alexandria was divorced from its Greco-Roman heritage, and pushed more towards its Arab heritage. I don't see this as a phenomenon that happens immediately after 1952, but rather gains traction in the 1960s when, for example, Alexandria saw the rise of statues of Arab figures in the public space such as Ibn Khaldoun and Sayeed Darwish, among others. How does the rebranding in Mammoura fit in with this? When you speak of re-branding, is it a matter of the state homogenizing the entire landscape across the country, without any consideration for local factors and idiosyncrasies of a city?

Mahmoud Khaled: I also don't see this rebranding as happening immediately after 1952. As you said it did take almost a decade for this process to physically and visually exist in the public sphere and Mammoura as a project is evidence of this, as it officially opened in 1959 and was promoted afterwards as one of the regime's achievements towards the promised social democratic state and assuring the official support to the middle, working class and farmers.

We also know, this rebranding process was not only about erecting buildings with new architectural aesthetics and sculptures of significant Arab and national figures in public spaces, but included the establishment of agrarian reforms and ambitious industrialization programs that led to a period of infrastructure building and modern urbanization. There was a political need to have these social and architectural projects to form a new Egyptian identity that served the new elite of the republican era. Theses projects included housing complexes, theatres, cultural palaces, parks and summer resorts. Architecturally, aesthetically and functionally, then, all these projects were designed in sharp contrast to the lavish lifestyle of the former royal aristocracy which added a strong political connotation to the style of these buildings and projects, and more generally to the introduction of 'Modernism' in Egyptian architecture. At least that's how I understand it.

Maamoura is located strategically next to the former royal Montaza palace and gardens, which I read as an intentional political statement to show that the new state can also design and build a protected gated space for its won elite. This beach resort is considered to be the prototype for modern bourgeois summer destinations and is one of the first gated community projects in Egypt, functioning as a city within the city with its architecturally unique residential villas, houses, and cabins mostly owned by generals, businessmen, and celebrities that came to form the new upper class. At the same time, more modest buildings were targeted towards the middle-class with public sector companies having access to properties that they rented out to their staff for affordable prices.

Mammoura Beach, Alexandria, 1995. Black and white promotional video of Al Mammoura resort project, found on YouTube.

AA: The problem of political branding is that it tends to destroy pluralism, as the state imposes a narrative from above, rather than allowing an organic story to develop through civil society. How does your understanding of branding, in an architectural sense, equate with oppression and the destruction of civic meaning?

MK: Personally, I don't see any contribution from the civil society in this whole process at all; everything was done by the state to the people, and mainly most of the projects were executed by the army itself which is something happening until now and my generation can definitely relate to it.

AA: You touch upon an important aspect regarding Youssef Chahine's films. From my readings, the struggle between Alexandria and the state extended to films: for example, Nasser-era cinema tended to reflect narratives that domesticated Alexandria. This in turn subverted the city into the national narrative. Chahine's films were not an exception, although it as only with his 1978 film Alexandria, Why? that he was able to challenge this trend, by breaking with the conventional narrative and realigning it with an emerging novel tradition that represented Alexandria as a place of "utopian desire." The renowned director started to see a relative change in the political culture of 1970s Egypt – if not the Arab world – that enabled his cinema to "recognize and redress marginalized social elements within Arab national identity…[by revisiting and engaging] the cultural and historical elements of distinct groups he thought integral to the appreciation of a collective Arab identity."[3]

In light of this, how much innovation and independence was Chahine allowed in the making of the 1961 film A Man in my Life? Was the film geared towards supporting Nasser's project? Or did Chahine situate the idea of justice in a national (or perhaps nationalist) narrative at the expense of local civic factors?

MK: I think in this film Chahine tried to abstract the ideologies and the principles behind the "free soldiers" movement by staging a melodramatic love story that contains a lot of guilt, pain, and heroism to highlight the struggle for social justice amongst the working class (here, a group of fishermen in Alexandria) in the year of 1938, when the country was still a royal monarchy. It is very obvious to me how he was very influenced by these ideas, principles, and hopes for the establishment of a modern and socially equal state, like many other artists and intellectuals in Egypt at the time. For example, I still remember many of my painting professors in Alexandria who are associated with or known as the sixties generation of artists, were preoccupied with producing art that was heavily engaged with the ideas of social justice, class struggle and full independence from colonialism. I honestly don't think these artists, including Chahine, were doing this work to compliment the political power, or as a sort of a contribution to the propaganda of the new regime. Rather, I think they – or let's say most of them – believed in these ideas and wanted to dedicate their production to contribute to the cause.

This is, in fact, the most interesting point for me: how can we now look back at the art production of this period, especially given the radical shifts since 2011, to how we understand the regime today? How does viewing the situation as a continuation of the 1952 state, reshape our relationship with our home country?

In terms of innovation, I am not sure to what extent the film was an original, given it was an adaptation of the 1954 American film Magnificent Obsession by Douglas Sirk, But I am personally not so crazy about this idea of originality; I find it clever how Chahine kept the structure of the story from Sirk's film but adapted the sociopolitical content in order to respond and engage with the political and ideological moment in Egypt at the time.

Video collage by Mahmoud Khaled of two films, both of which were important source material for him during the formulation of this comission: A Man in My Life, dir. Youssef Chahine, 1962, Egypt, and Magnificent Obsessions, dir. Douglas Sirk, 1954, USA.

AA: Fascinatingly, this recent body of work metaphorically touches upon building materials such as glass and marble, which you argue have been widely utilized in state-sanctioned architectural projects in Egypt over the past thirty year. Here, I specifically want to point to the piece A Rare Glimpse into the Recent Moments When People Lived in a World Turned Upside Down (2016) in which you used eight computer-generated images of carrara marble printed on wallpaper and sixteen double glass panels, accompanied by images and texts that occupied almost half of the space of the exhibition.

Is there a particular state logic behind utilizing building materials such as glass and marble? Does this have any relationship to Mubarak's political projects and neoliberal policies?

MK: Yes it does. I wanted to do something physical, imaginative and semi-fictional, using material that would speak directly to the content of the installation. I decided to use the format of the memorial as a site from which to stage the content of the project; of course here, marble makes perfect sense, as a permanent noble and monumental material that has been used excessively in most of the governmental projects in Egypt during the past thirty or so years, which is of course, the era of Mubarak.

When I looked back at the use of the material and its existence in state-owned or run buildings, I started to see the sharp contrast between marble and the kind of modest, humble and relatively cheap building materials that was used in the late 50s and 60s by the regime. For me, this shows how the state wanted to manifest itself and assert it's power architecturally and in public spaces, whilst pointing to the shift in aesthetics and values from the 60s to the 90s, and so I was keen for the installation to reflect this.

AA: The 'Maamoura's Victims' text by Judge Hassan Jalal, published in Al Hilal Magazine in February 1955 just few years after the '52 state' started, presented a report on the atrocities, horrendous conditions and systematic tortures in a prisoner camp on the King's properties, which later became the land on which Maamoura was built. It is an insightful artifact from a very romanticized period in the Egyptian and Alexandrian popular imagination. Would you say that your work in this regard is a strong statement against nostalgia?

MK: William E. Jones, who is one of my favorite artists said recently in an interview that 'Nostalgia is a sympathetic feelin''[4] – and I completely agree with him.

Unfortunately, Alexandria has been always romanticized in the popular imagination. I can even sense this when I talk about the city with my friends and colleagues from Cairo. It's something I used to be very sensitive about it. Nostalgia became the scary ghost that I tried to kill while I was developing and working on the exhibition, and I hope I did that – though I don't know. I think the problem for us Alexandrians is that we have been over saturated with nostalgic narratives and representations of the city in books, films, and photographs (and now even on social media) but it's still the city we live and work in. And so, it is hard to ignore the overarching sentimentality.

That is why I tried for a long time to avoid working on anything related to Alexandria and its history – near or far – because you can never escape the language and aesthetics of nostalgia when talking about the city in the field of artistic and cultural production. This idea shifted for me in 2011, when I saw everything in the city becoming highly politicized and very active, instead of being forever decaying and romantic; it was then that I realized that I can talk abut the city in a way I was unable to before, mainly because of my own self-censorship towards this fear of being nostalgic.

Jalal's text was also a huge discovery for me – it made everything feel similar and yet different all at once, and that's why I wanted to use it in full length in the installation. First of all, it gives us a glimpse of Maamoura when it was just an empty, neglected wasteland, and how even during this time (late 1940s/early 1950s) it was a stage for human rights violations, torture and the exertion of power by the state. Secondly, the fact that it was written by a judge, whose profession is to protect the values of social justice and dignity in society, he is also fully supporting the 1952 state (which I believe we are still living an extension and the continuation of this era).

I also think my fascination with the text has a lot to do with the fact that I was born around a bunch of structures, monuments, and buildings which are gradually vanishing from the cityscape, yet I still don't know much about the socio-political history of Maamoura or how things were before these structures were built. At the same time access to information as an artist or a researcher is restricted by state authorities; you will find a lot of intentional obstacles in your way, so as not to ask or uncover anything that may conflict with the state-sanctioned narrative. Here, the act of knowing becomes a highly politicized endeavour and pushes this persistent nostalgia out of the frame.

AA: The use of the Maamoura's Victims as a textual document/ testimony is described in the exhibition text as an element that is highlighting and activating the "haunting similarities" between the methods of the monarchy and republic, which you argue, puts the document in a completely different light, making it even more relevant when read in the present. Based on this reading, I would like to ask: could not the observer of your work suggest that in attempting to condemn the monarchical period as being just as bad as the republican era, you have indirectly vindicated the latter? Historians would probably not disagree with your account, but they could argue that oppression and torture increased exponentially and systematically under the Nasser regime, making the King Farouk era pale in comparison.

MK: Well, I don't think the work is trying to vindicate or blame one era or another as both eras are very difficult to understand or judge in their entirety. I also hope the artwork works to complicate and problematize moments in our history, instead of just giving a statement about who was more oppressive than the other, because things are far more complicated than this. This is especially the case for artists; perhaps it is easier for researchers, academics, and historians because they have a clearer methodology for how to draw their conclusions. Yet for most of us – and by us, here I mean the artists whom I am close to and am in dialogue with – we are all producing and speaking from a position in a world that does not make any sense at all, and art seems for some of us, still the only possible long-term attempt to deal with this mess that we are collectively sharing.

The work is imagining a memorial, a space for remembrance, which as an act includes thinking and reflecting with a strong sense of monumentality and spectacle. Memorials are traditionally built after long civil and grassroots discussions, and to remember key social and political events. Yet my generation only inherited memorials; we never experienced or witnessed the building of those we inherited, and so the aim of my work is to both consider and commiserate the absences in constructing our own history, emotionally and meaningfully.

Mahmoud Khaled (b. 1982, Alexandria, Egypt), lives and works between Egypt and Norway. He studied fine art at Alexandria University in Egypt and in Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway. His work traces the boundaries between what is real and what is hidden, disguised or staged. His artistic practice is both process oriented and multidisciplinary. Mixing photography, video and wall painting with sculptural forms, sound, and text, his works can be regarded as formal and philosophical ruminations on art as a form of political activism, as an object of desire and as a space for critical reflection. His artistic vocabulary is composed of appropriated forms that have been displaced from their original context thereby proposing alternative meanings.

Khaled's work has been presented in solo and group exhibitions in different art spaces and centers in Europe and the Middle East, including Whitechapel, London (UK); Edith-Ruth-Haus, Oldenburg, Germany; BALTIC Center for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK; Galpão- Videobrasil, São Paulo, (Brazil); Gypsum Gallery, Cairo, (Egypt); Centre Pompidou, Malaga, Spain; Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam (SMBA), (Netherlands); Bonner Kunstverein, (Germany); UKS, Oslo, (Norway); Salzburger Kunstverein, (Austria); Contemporary Image Collective/CiC, Cairo, (Egypt); Sultan Gallery, (Kuwait). His projects have been featured in several international biennales such as LIAF Biennale, Lofoten, (Norway). BManifesta 8: European Biennale for Contemporary Art; Biacs 3, Seville Biennale, and 1st Canary Islands Biennale, Spain. In 2012 Khaled was awarded the Videobrasil In Context prize and he was shortlisted for the 2016 Abraaj Art Prize.

[1] Alexander Reid Ross, 'A New Chapter in the Fascist Internationale' in CounterPunch, 15 September 2015: http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/09/16/a-new-chapter-in-the-fascist-internationale/

[2] 'Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.' The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Karl Marx 1852.

[3] Malek Khouri, The Arab National Project in Youssef Chahine's Cinema (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2010). 117.

[4] Quoted in Mousse Magazine. Issue 56. December 2016–January 2017