Interviews

Homeland(s)

Hrair Sarkissian in conversation with Raed Yassin

I've known Hrair Sarkissian for over a decade, since we met in his hometown Damascus. We eventually became very close friends and even shared a room together while we were both living in the Netherlands. Because of this personal perspective, I have found it difficult to formulate objective questions about Sarkissian's artistic practice – there were too many details clouding my mind about personal happenings and events that took place in our lives. In the end, I found a virtual barrier through which I could ask what needed to be asked: email. For this interview, I wanted to know why Sarkissian recently introduced an essentially completely new medium – performance – into his practice, even though most of his work is non-performative. His recent piece, Homesick (2014), is a two channel video installation in which Sarkissian films himself destroying a perfect model of his family home in Damascus, Syria, with a sledgehammer. This new turn provoked this conversation.

Raed Yassin: In your latest exhibition Imagined Futures (2015) at the Mosaic Rooms in London, you displayed earlier works alongside recent pieces in the same space. Can you explain how the works came together in this way, even though they were made in different periods?

Hrair Sarkissian: Both of the works on show in Imagined Futures dealt with the subjects of war, loss and fear. The Front Line series (2007) is about the aftermath of six years of bloody war in the enclave between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the self-proclaimed independent Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh, where more than one million were exiled or killed and many families lost their loved ones. As for Homesick, it is about losing your home through war, the pain of remembering that place, and the feelings of hatred that come from such loss. I decided to group these two series of works together, despite the seven-year gap between them, to bring to the surface the past and present realities of the atrocities caused by war.

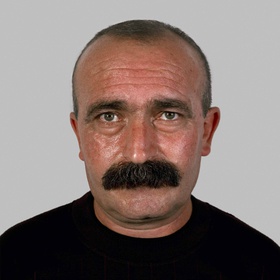

RY: Homesick is a two-channel video installation in which we see, on one screen, a maquette model of your parent's house in Damascus that has been destroyed. On the screen facing this, we see you holding a sledgehammer. Why did you choose to make a work like this, which is far more performative in some ways to your previous projects, no least given that you are working in video here, which moves away from your preferred medium of photography? Is it related to what is happening in Syria now?

HS: For over four years, the situation in Syria has continued to get worse and people have lost hope. During these past years I have refused to work directly on what is happening in the country for many reasons. One of them is to respect the people who are going through these terrible moments, being killed, loosing family members, or becoming exiled in refugee camps. Meanwhile, I kept thinking of my family, who are still in Damascus in the same house where I grew up. Every day my thoughts are with my parents and family who, like everyone else, can't see an end to this atrocious situation that everyone is enduring. So I decided to make a work about our own home, the one I grew up in and think about constantly. It could be anyone's home and could be destroyed for different reasons besides war. For me, there is always the fear that something might happen – that a missile will hit the building, for instance, and turn into rubble and I will lose everyone and everything. Destroying the building also became a way to break the imagined image that something bad might happen.

As for the performative aspect of this work, initially there was no intention to include myself because I wanted it to be general rather than personal. Eventually, I decided to add headshot footage of me hitting the model with the sledgehammer, where the viewer can observe my facial expression while destroying my own home.

RY: You are Syrian but have Armenian origins, and you now live in London. What does home mean to you and where is it now?

HS: Home is where I have a roof over my head – the place where at the end of the day I want to be and feel safe, among the things that I have created, gathered and tied myself to, and also a place where I can be with the people that I share my life and feelings with. It took me quite a long time to find the proper place and meaning of the word 'home', especially after leaving Syria, the place where I grew up. For a while, before going abroad, home meant the place where I was brought up; the physical place where I belonged, where I had to go back. Throughout the time that I was travelling, and I moved between cities that I did not have any personal ties to. The meaning of the word 'home' has changed for me as a result. It is a place where I can find refuge: the door separates the outside from the inside.

RY: You've done a number of projects in Armenia, including the one you mentioned, Front Line (2007), which is about the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the self-proclaimed independent Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh. How did you feel when you first visited Armenia?

HS: The first time I visited Armenia was in 1986, when I was 13 years old. It was a dream come true to visit my homeland, and I felt proud simply being there and visiting all the historic places. These places play a large role in shaping our personalities as Armenians living in the diaspora and visiting filled the gaps and missing images of things we always heard about but never saw.

In 2001, I went to Yerevan. I was very excited at the idea of going back and looking at things with a different, adult perspective. When I arrived I was disappointed and felt like I was seeing the reality – the current difficult situation of the country and people – without having the historical blinkers on. The increasing level of poverty and widespread corruption made me want to close my eyes and leave. I wanted to avoid tainting the memories that we have been constructing all these years about the homeland, the return, and the historical glories.

RY: Can you elaborate on your personal relationship between Damascus and Yerevan, especially since neither of them are your cities anymore?

HS: In some ways, it has always been sad to be in Yerevan because of the situation the country is in, with poverty spreading everywhere like a disease. I always felt uncomfortable working there and somehow I felt that I was documenting the end of a country that I was linked to through language, history and culture. As for Damascus, it is the city where my heart belongs, where my countless memories are contained, and where I grew up. I lived in this city physically, while I lived in Yerevan more figuratively. I miss Damascus, its stories, people, and noise, but not so much Yerevan, which is more of an imaginary homeland.

RY: How do you view the function of language in photography and art?

HS: I see photography and art as both ways to communicate with others. When it comes to my photography, language is the only tool of communication that allows me to create a dialogue with those standing and looking at my images. It also allows them to express and voice their own thoughts.

RY: In many of your works there is an absence – a sense of stillness that leads you to a situation that occurred beforehand. For example, in Execution Squares, you present fourteen large colour photographs showing the sites of public executions in Syria. Can you describe this absence?

HS: The absence of an act or of action in my images is related to the absence of time. In these works time does not go forward, they are stills of things that happened in the past, yet we look at them in the present.

RY: I also notice in that you often like to hide the motifs in your work. This is most evident in the Unexposed series, in which you focused on the descendants of Armenians who converted to Islam to escape the genocide that took place in the Ottoman Empire in 1915. In the images, we never see a whole body, or a face, even – we only see parts of that person, with the rest shrouded in dark light. What sparks your interest in hidden stories, subjects and people?

HS: I do not hide the motifs of the work, and I'm not interested in hidden stories, subjects or people – my topics are simply related to me, to where I come from, and my background. These themes might be hidden for some, but not for me. Rather, I avoid putting all the information or the elements of the work right in front of the viewer and making it easy to read. I prefer to create this open space and let the work create a sort of dialogue with the viewer, leading them to ask questions and get involved visually and conceptually.

RY: You went to Istanbul to make istory (2011), which is a project where you attempted to access the history sections of various public and semi-public archives in the city, looking for archives that acknowledged Armenian history. Where did the idea for this project come from, and how did it unfold? Did you feel uncomfortable or threatened at any point?

HS: The idea for the project came from an accidental visit to an exhibition held by Istanbul city hall. At the entrance there was a timeline that started with the creation of the Ottoman Empire and ended with the creation of modern Turkey. What I realized during this show was that the only date that was missing from the entire timeline was 1915, despite it being the date of the Armenian genocide. For me this meant that the state was saying that nothing significant happened on this date, that Armenians were not killed or expelled. For me this also meant that to them the Armenians did not exist and, consequently, that I didn't exist either. I often feel like this when I visit Turkey. Generally, when I am there, I do not openly reveal that I am Armenian or that my grandparents are originally from eastern Anatolia. I tend to hide who I am and only mention that I'm Syrian – I'm always nervous to tell anyone in Turkey my name in case their reaction is negative.

The project istory was realized with the help of SALT (at the time it was called Garanti Platform), who provided me with an official letter explaining my project as well as making contact with the officials and asking their permission to photograph the libraries I visited. The officials in these offices were very suspicious of me because the moment that they read the letter they saw my very obvious Armenian name, and the expression on their faces would change. I could see them wondering and linking me immediately to Armenian history and the genocide. This was one of the most difficult processes I ever went through during a project for many reasons. Firstly, I had to hide myself constantly and not mention what the project was really about. Secondly, in all the places I visited I was not allowed to touch the books or any other kind of documents. Sometimes, I was escorted around the libraries and the officers would follow and watch me while I was working. Each time I took a picture I had to show them what I had captured.

RY: What does identity mean to you? Do you have a clear sense of identity?

HS: For me, identity is a burden – a heavy weight that travels with you and makes you feel both proud and afraid, strong among the weak, and vice versa. The more I cross borders and the more I become exposed to security checkpoints, the more I understand what 'identity' means. Holding a Syrian passport, an identity that you didn't choose but were born with, has suddenly become problematic and it makes you undesirable or unwelcome. All because you carry a piece of paper that defines you: your identity.

RY: Your father is a photographer who used to run a photography studio in Damascus. You worked there for many years yourself, before subsequently developing your career outside of traditional studio practices. I'd like to hear more about your relationship with your father – before and after you worked with him in the studio, and especially after you created a project about him called Sarkissian Photo Centre (2010).

The Sarkissian Photo Centre project mostly deals with the memories I had, the experience I gained, and the people I met throughout the years in my father's shop. It was also a way to sit in front of my father's lens, look through it and share the grief and the loss of his dream, which was to be the oldest colour photo lab in Syria. Sadly the studio had to close down.

RY: On the topic of studios, I imagine this is what sparked the idea for your award winning series Background (2013), where you document studio backgrounds and settings in six cities in the region: Amman, Beirut, Byblos, Istanbul, Cairo and Alexandria. Can you elaborate more on this?

HS: The idea for the Background series came from a photograph taken at my father's studio of a grey plain background. One layer of this project was about documenting these studio backdrops, which were facing the end of an era, and also how they had witnessed and been the literal backdrop to many different societal structures and historic periods in the region.

The closure of my father's photography lab and family business seemed to coincide with the broader disappearance of a particular type of backdrop from commercial studios across the region. This disappearance seemed to me to index the end of an era in the history of photography in the region, and I felt it was worth documenting somehow. The practice of studio portrait photography was dying out due to the growing reliance on digital technologies amongst both practitioners and patrons in producing or mastering a portrait and eventually manipulating these images.

RY: In this sense, there is this feeling that your work is always performing a kind of reconnection with history through the process of relating with it. I wonder if this assessment resonates with you?

HS: Actually it does, although I never considered taking the role of a performer in my work, but the fact that my work turns around my background, which time has a great influence in its structure, and an additional fact that I keep traveling back and forth in this time zone, I feel myself as a performer. It's not a primary element in my approach, but it just happened that it is there.

RY: To this end, I wonder how far you might describe your work as performative?

HS: Maybe the performing part in my work is more personal and not intended to be for the public. But generally speaking, when photographing with a large format camera, the entire process of preparing the setting, looking through the view finder, and some other technical aspects is rather performative, but this doesn't concern me as much as my entire attention is directed towards what will be in the image itself, and what the message would be for the person who would stand in front of it and start gazing.

Hrair Sarkissian is a photographer. Born and raised in Damascus, he earned his foundational training at his father’s photographic studio, where he spent all his childhood vacations and where he worked full-time for twelve years after high school. In 2010 he completed a BFA in Photography at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam. He lives and works in London.