Interviews

Doing Performance

Hassan Sharif in conversation with Nujoom Al Ghanem

In this interview, filmmaker Nujoom Al Ghanem speaks with Hassan Sharif about the question of performance art and its histories from the perspective of the Gulf. The conversation starts in Europe, where Sharif studied at The Byam Shaw School of Art, London, graduating in 1984. When Sharif returned to the UAE he set up Art Atelier, a studio space and meeting place, that same year. Sharif began staging interventions, organizing some of the first exhibitions of contemporary art in Sharjah, as well as translating excerpts of art historical texts and manifestos into Arabic, including the Suprematist manifesto, so as to provoke a local discourse. In 2007, he co-founded The Flying House in Dubai. This conversation starts with a key moment in Sharif's life – when he began engaging in performance – and expands to a consideration of what performance is today. What emerges is a framework with which to consider the Platform 009 question. As Sharif himself notes at one point: 'Now we need artists from the Middle East to come forward and write about their own history of art.' Sharif is one such artist.

Nujoom Al Ghanem: Before we begin, can you give an overview of what you feel are the genealogies of performance art in North Africa and the Middle East?

Hassan Sharif: If we go back through the history of performance we will find Frank Wedekind, who was active in Munich in 1905 before the Dadaists formed in Zurich. Wedekind would perform among an audience: a small but significant one, nonetheless. And for such a genealogy we can also look at Filippo Tommaso Marenetti, an Italian poet who, in 1909, published the first Futurist manifesto. In the same year he spread the manifesto to Moscow, where the Russian Futurists preached that art needed to occur in the streets, and that it can't just be visual with drawing but must encompass many forms and media. It created a whole movement of engineers, doctors, poets, writers and actors. Do you remember in the studio in the Al Marijah [Art Atelier] that there was a book on performance art titled Performance: From Futurism to the Present by RoseLee Goldberg? In Al Marijah, and before, I used to research the source of performance art and tell UAE society that performance art exists.

NA: Let's trace further back than Al Marijah. How did performance move from Europe and eastern Europe towards North Africa and the Middle East?

HS: It travelled with a small group of people who understood what performance art was. They went back to their countries and they spread the word about this art form. Performance did not arrive in North Africa and the Middle East by coincidence, it was brought over: the history of art was written and documented by Europeans. Now we need artists from the Middle East to come forward and write about their own history of art.

NA: When did performance art begin in the UAE for you?

HS: Between 1982 and 1983, I was coming back to Dubai during summer breaks from my studies in London. My brother, Hussain, used to bring a group of about four or five friends to my house in Satwa and my earliest performance work was with this group. They became my audience. At a certain point I thought, why don't we take this to a more innovative stage; why don't we go to the desert? It was August. It was a beautiful thing that they agreed to drive out to the desert in that heat. We had a shovel and we used to dig holes, collect rocks and throw rocks out there. I would take photographs and develop and print them myself in the dark room at Byam Shaw when I got back to London. I showed my fellow students at the college what I had been doing during the summer. I see now that I started this kind of art, performance art in Dubai, in a small room in Satwa without much technology – only a camera and a recorder to document the audio.

NA: Let's talk about the book that you mentioned, Goldberg's Performance: From Futurism to the Present, and the Al Marijah Atelier in Sharjah. Can you clarify these beginnings?

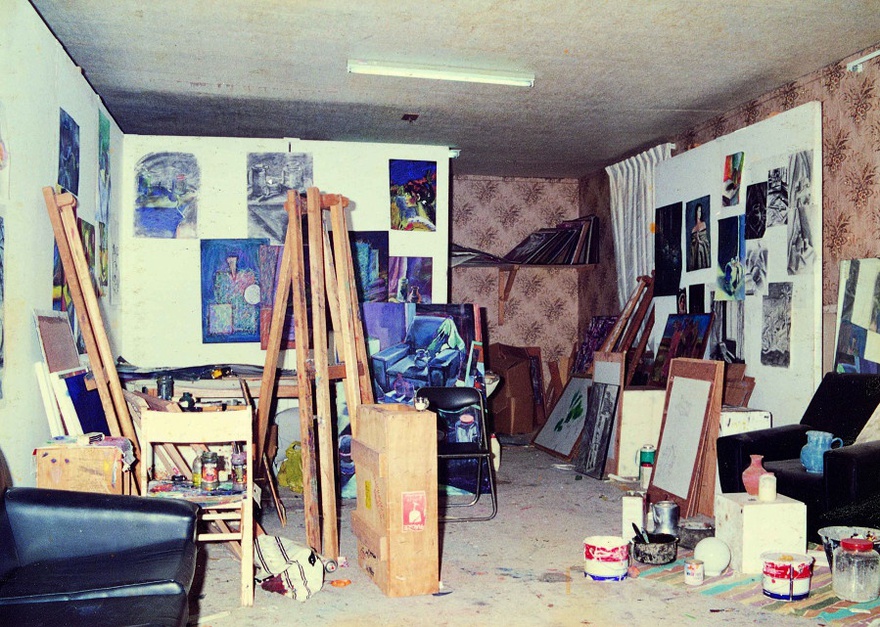

HS: In about 1984 or 1985, Emirati poet Khalid Bader Albudoor and I wrote an article about Goldberg's book in the magazine Tashkeel, which was published in the UAE at that time. We translated excerpts of Marenetti's Futurist Manifesto into Arabic. I even remember Khalid drew a portrait of Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, a very beautiful drawing. It was a matter of spreading the word more and broadening awareness. The group grew to include you [Nujoom Al Ghanem], Khalid Bader, Ahmed Rashid Thani, Hussain Sharif, the playwright Yousef Khalil and many others. During that time visual art took on another dimension for us that could encompass literature, cinema and movement. The studio wasn't just a place where we made paintings: it was a place where we would negotiate important discussions. We called it a factory. 150 years ago, Edgar Allen Poe talked about a 'factory of literature' and so we moulded our ideas after that and invited Poe into our studio in Sharjah.

NA: What was the reaction towards performance art at that time? Was there much understanding?

HS: It's wasn't a problem if people didn't understand – what mattered was the spark. Creating a spark is important, provoking people is important. In the 80s I wasn't concerned with exhibiting my paintings; I wanted to show only objects or performance works because this provoked the viewer. I always say that the role of the artist is to not only to create visual artworks but also to produce the right audience – to create the viewer.

NA: Were the group who hung out in the Al Marijah Atelier participants in these performances or were they your audience?

HS: I can't answer if they were participants or an audience. They were artists, poets and writers and they all had different views on life and the world. Yet when we got together and talked in the studio in Al Marijah we shared similar ideals. Khalid would talk about poetry, and I used to draw squares, while you, Nujoom, would be writing. Everybody in Al Marijah was an alchemist sitting and transforming stone into gold. And we knew, we understood with clarity, that the stone could not be transformed into gold! Yet despite all that, we insisted that we had to do something because there were certain things that were not available here.

NA: Does performance art differ between one country and another within the region?

HS: Performance does not differ between one country and another. It differs, however, from one artist to another and that has to do with the history of performance art. Let us talk instead about something that happened in Singapore – every year they have a festival for performance art. I found a small book from this festival that explained that one of the participating artists didn't believe in photographical documentation nor do they trust film documentation, and so one member of the audience is requested to write about the experience as its only documentation. How, then, do we read a performance? This is a big change to what is understood from performance art. We need to pay attention to such progression.

NA: How do we compile a history of performance art in the region?

HS: Re-read the magazine Tashkeel, especially the years 1984 and 1985. Tashkeel was started in 1984 by my brother Hussain Sharif and he really fought to make that magazine, which documents a lot of conversations between artists and writers. Several organizations are now researching this subject, even though a lot of what remains is just documents and simple newspaper articles. But these are still important because society or the environment has since progressed and today we can understand things that weren't clear at that time.

NA: How did your generation evaluate your performances?

HS: My generation was harsh, very tough and one had to fight a lot. Now it is better and more beautiful because the new generation has more independence and a broader view. Therefore I think there is progression and change. My generation used to just say, 'What are you doing? Throwing stones in the desert? Why?'

NA: We belong to a conservative society in which tribes are very important. How did this type of society deal with such experiences in art? Have the topics of ethnicity and race been approached?

HS: Like anything new, it is hard for people to accept things, and back in those days a rejection might have stimulated me more, whether it was because of race or not. But now that I reflect back I can see why those rejections happened and I totally understand them. After all, my art talks about things that are not related to tradition, race, gender or ethnicity. That is because I want to explore different spaces, not because I want to be different. Again, as I always say, the process in creating my work is the sole reason that keeps me wanting to create art, and by discovering new spaces I find myself always curious about new things. It is the same with society, despite belonging to any specific tribe or clan. I am not sure if I answered your question here, but: society expressed their surprise for my work with some sort of rejection during the 80s; now they are welcoming it. That makes me so happy because it means that they found another way to express their surprise. I can see everyone evolve, just as I am evolving in the process of my work.

NA: Who is the audience for performance art in this region?

HS: The audience is a new generation that is aware and learned. As I always say, the most important thing is education – the existence of colleges and the schools that have large graduating classes every year. These groups need art that's different from the art of the past. Why do they invest in building big museums now? These museums are going to be transformed into the likeness of a school, not just places where artworks are exhibited. They are instrumental in the movement of knowledge within society. The audience is there, the artist is there and the artwork is there. So there is progress. I'm not pessimistic. I'm always optimistic.

NA: How did artists approach the subject of gender in performance?

HS: I think performance has reached a stage that's much more progressive and the role of the body is important. Mohammed Kazem uses his body, his tongue for instance, and exhibits it as photographs. Ebtisam Abdulaziz uses video as documentation of her performances. We think, in the eastern world, that the subject of sexuality is very sensitive, however many countries are no longer concerned with this issue and no longer look at sexuality as a temptation in the way we look at it here. This eastern outlook is strange; animalistic by nature, we might call it. There are many things that need to change, in terms of teaching and social relationships, so that we view the body from a philosophical perspective in a way that is different from just temptation.

NA: How does performance, with its ephemeral nature, allow for more subversive, transgressive or political forms of public and institutional participation across the region?

HS: Performance art has a short lifespan but its effect remains. The traffic lights do not stay red all day long, they are transformed to green and to yellow. When the viewer of a performance travels from one place to the next he tells a story, creates a narration and ultra-narration, about what he saw.

NA: What are the legacies, potencies, and potential pitfalls of re-staging live performance via lecture, panel discussion, conversation, text and exhibition?

HS: It is the role of the institutions, especially the museums that are coming here soon, which are not just museums but also have spaces for learning, for exhibition, for dialogue. These are all spaces that can be devoted to performance. The entry of performance into the educational curriculum is also very important, as well as at college and university level.

NA: Would you participate in performance art today?

HS: The situation is such that institutions are now interested in performance art. I think that it’s better that I don’t go back to performance art than to return to it simply because an institution is concerned with it. In the 80s I did performance works and there was no reason and that was the beauty of them. So I don't think that I will do performance now. I presented a video work two years ago, Approaching Entropy (2013) at the Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, documenting how I made an object that was encased in glass in front of the viewer. I see that this is much closer to me and as a result I didn't call it performance. I was very affected by this idea of writing a performance; why don't we speak performance? I can speak and it becomes a performance. It's not important to me to use my body. There are so many artists who do this. Tarek Al-Ghoussein, for example, uses his body and photographs it. There are so many examples and I'm sure that the number of names will increase. It's not important that Hassan Sharif does performance.

Hassan Sharif has made a vital contribution to art and experimental practice in the Middle East through 40 years of performances, installations, drawing, painting, and assemblage. Sharif graduated from The Byam Shaw School of Art, London, in 1984 and returned to the UAE shortly after. He set about staging interventions and the first exhibitions of contemporary art in Sharjah, as well as translating excerpts of art historical texts and manifestos into Arabic, so as to provoke a local audience into engaging with contemporary art discourse. In 2007, he was co-founder of The Flying House, a Dubai institution for promoting contemporary Emirati artists. An early work by Sharif was included in Whitechapel Gallery's recent survey of the history of abstraction, Adventures of the Black Square: Abstract Art and Society 1915-2015.

Translated by Fatima Albudoor.

Watch video documentation of Hassan Sharif making work between 1995 and 2013, edited for the Ibraaz channel by Craig Stallard, here.