Interviews

Visualizing Displacement

Foundland in conversation with Nat Muller

Foundland’s Lauren Alexander and Ghalia Elsrakbi talk to Nat Muller about their new exhibition Escape Routes and Waiting Rooms that recently opened at ISCP (International Studio and Curatorial Programme). The last few years Foundland’s practice has focused primarily on analysing stories, images and social media that come our of war-struck Syria. In their current show they investigate personal narratives of Syrian displacement and migration through domestic tropes. Foundland are currently the first artists-in-residence at ISCP supported by Edge of Arabia in partnership with Art Jameel for artists from the Middle East.

Nat Muller: In the title of your exhibition Escape Routes and Waiting Rooms you distinguish between two actions, 'escape' and 'waiting' that are formative for the plight of refugees: departure followed by displacement and then forced waiting for the possibility to return back home or for the cessation of violence. In other words, you sketch out the uncertainties of geography (place) as well as the uncertainties of what is to come (time). It almost seems as if you have treated space and time differently in your installation. Is it important to understand these conditions differently?

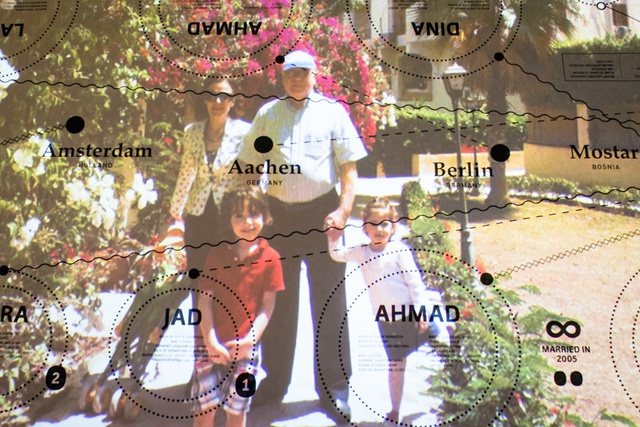

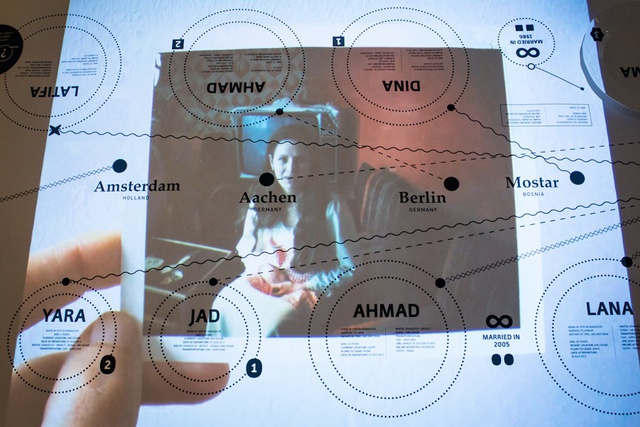

Foundland: Aspects of time and space are crucial concepts that should not be considered separately. The collapsing and reformulation of geography and time are very important when thinking about the migration and displacement of Syrians. In the installation piece Friday Table (2013–14) we re-stage a family table setting based on the Friday lunch seating plan as per Ghalia’s family’s meal ritual in Damascus. The family table originally had 19 people seated around it, now only four people remain in Syria. A map drawn onto the table shows the evacuation and movement of the family from their usual table seating to new destinations around the world, from Germany to the Netherlands, to various destinations in the Middle East. Migration reaches back generations, to when Ghalia’s grandmother moved from Yugoslavia to Syria in the 1950s. The map shows movement from and to Syria in times of political and economic crisis.

NM: Apart from matters of access, how important was it to have Ghalia’s own personal story in there? Does it become a collective narrative?

FL: It was relevant for us to use Ghalia’s family narrative, not because it is a personal story, but because it is an example of displacement that many Syrians are currently experiencing, particularly middle class Syrians who do not have a specific engagement with politics. Though we draw on the specifics of her family’s story, it plays a part in a collective when they don’t want to, yet feel they need to. Despite not being involved in politics they are always in some way implicated in the complex and dangerous context inside Syria. They have the feeling that they need to move in order to secure a future for themselves, for their families and businesses. Such stories form the beginnings of new migration patterns and shifts in entire communities within the Middle East. We witnessed this, for example, in 6th of October City, a satellite town outside of Cairo, where thousands of Syrians have settled in the last few years.

NM: You make use of domestic tropes, the dinner table and the tent, to illustrate patterns and narratives of migration. Why are these particularly forceful for you? And can you elaborate on how you worked to visualize your research: what made it into the final display, what did you decide to leave out?

FL: Our foremost intention with using these domestic tropes is because they are understood by the general public. It allows us to speak about topics related to politics in a way that is accessible and provides an alternative image to news media. Most viewers can easily relate to the image of a dining table and the ritual of family dinners, and will be able to project their own imagination about these occasions onto the work. When collecting and editing information related to Friday Table it was important for us to include images of the past as memories that exist around the setting of the table. For those who used to participate in the daily meals but can no longer be present, the ritual of communal meals only finds a place in the images that remain. Images or memory, which were once engrained in daily habits become a more important leftover than the table itself. In the creation of the table and tent installation, we had to leave out a lot of information, and the viewer will certainly be left with many questions related to reasons and particularities of patterns of migration. In the case of Waiting Room (2014), the tent installation included in the exhibition, we revisit a very well known image in the media, the white tent, commonly associated with refugee camp dwellings. The tent reminds us of displacement, helplessness and emergency resettlement. However, many of these tents that are being set up at a rapid pace at the Syrian borders with Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon, are proving to be far from temporary. For the tent installation, we asked displaced people from different backgrounds to sketch their housing situation prior to departure from Syria, as a way to depict and make visible what has been left behind. Juxtaposed with the instability and reality of their displaced situation, is a collection of ground plans for houses that enables the viewer to consider emergency living habitation as an involuntary yet permanent reality. For some people it was a very painful experience remembering their previous home. Many no longer have visuals or evidence of the places they left behind. By retracing the living structure of the home, one remembers the permanence, ritual and structure embedded within that place. Although the works are based on personal stories and observations we do not see them as documentary, but rather as incomplete and subjective interpretations and analyses of situations. We use stories, personal artefacts and image collections of reappropriated news media to try to translate a state of being. We would like to express what it feels like to be stuck, with no option of escape, physically and mentally.

NM: Would you say that the tent then also becomes a type of archival memorial? I am reminded of Palestinian artist Emily Jacir’s 2000 piece Memorial to 418 Palestinian Villages which were Destroyed, Depopulated and Occupied by Israel in 1948, which shows a white UNRWA tent with the names of the Palestinian villages embroidered on them. Does your tent operate similarly?

FL: We use the tent as a metaphoric placeholder, standing for displacement and the state of finding oneself in between. We are concerned with the fluctuating state that exists between being involuntarily displaced from a life that you once knew, and having to deal with constructing a new reality. All over the world today people are being relocated to ‘temporary’ camps and dwellings until, with time, these places become integrated into the surrounding urban structures and in some cases develop into cities. The tent installation functions as a house or urban plan in motion, rather than a slice of the past or a memorial as in Emily Jacir’s work. We do see similarities with her work in our desire to collect and archive. However, the house drawings that we collect from Syrians are subjective stories.

NM: You speak about providing an alternative image to the news feeds. Can you elaborate what you find lacking in news images from a visual and narrative perspective?

FL: Our desire to present alternative imagery or narratives does not really stem from a dissatisfaction with news imagery. In Map Projections (2014), the third component of the exhibition, we reappropriate news imagery to create a projection that is a flickering map of the image of Syria. News images and reporting are formulated by many different factors like the limitations of journalists and photographers to move freely, the interpretation and translation of information, the politics of broadcasting and the media industry’s desire to sell their products. We don’t aim to create a better or more truthful narrative. We would like to use the visual language of broadcast media, which is how most people learn about current affairs, to provide the audience with an alternative perspective.

NM: In previous projects such as the publication Simba, the last Prince of Ba’ath country (2012) and Journey to Ard al Amal (2012) you researched the iconography used by the Syrian regime as well as the Syrian opposition to get its message across. Often the imagery is borrowed from stock photography, cartoons or popular culture. Can you talk about the imaginary these iconographies create, and what methods you used to create an imaginary for your current exhibition?

FL: In these previous exhibitions we began our investigation with a fascination for propaganda imagery, from the pro-Assad regime, as well as the Syrian opposition. In both exhibitions we collect, analyse and try to come to grips with why and how these images are created. What sort of ideology or myths are employed by the 'image-maker' when using computer software to create this imagery. In the case of Simba, the last Prince of Ba’ath Country, we focused on the creation of myth through the use of Western-oriented imagery such as from Hollywood film, video game imagery and stock photography that is used, reappropriated and recontextualized to serve the purposes of the regime. It has been fascinating for us to see how these images that circulate on social media convey a completely new message within the context of the Syrian conflict. In Journey to Ard al Amal we try to understand how oppositional propaganda and protest was constructed by looking specifically at examples of reappropriated Disney and Anime characters. What is interesting to notice in oppositional propaganda is the manner in which characters in popular culture come to represent oppositional leadership, something that is sorely lacking in the Syrian context. Images not only portray a recontextualized version of their original source, but tend to become iconic for a movement or ideology that is otherwise difficult to represent or visualize.

NM: There has been much talk about the role of social media since the 2011 uprisings in the Arab world. Social media platforms are used by the Syrian regime and the opposition alike, and also are a channel for citizen journalists to bear witness in places that have become either too cut-off or too dangerous for the mainstream media. You have worked extensively with online resources for your projects and issues of mediation are central to your practice. What has been particularly striking for you when looking at Syrian online behaviour, and which aspects of social media do you integrate in your own work?

FL: It has been very interesting for us to witness the initial use of social media in the Syrian context. From the first stages of a profile image being used to announce political standpoints, to more sophisticated methods of using Facebook and Twitter as an alternative distribution channel for news that is otherwise inaccessible. We conducted an important interview in 2013 with Egyptian artist Hani Rashed. He explained that in Egypt the revolution brought a new understanding of the image and what the image in combination with political opinion can mean to people. In his opinion the Egyptian revolution of 2011 helped people realize that they are part of an image culture, which they too can influence. In his artwork he focuses on creating political images specifically for social media.

There are many similarities in how political imagery is created and spread online between different contexts in the Middle East. For example, in Syria and Egypt humour is used as a way of creating viral images with political messages. As foreign media is severely restricted in Syria social media plays a crucial role in connecting Syrians in exile with Syrians on the inside. A good example is Abounaddara Film Collective whose work with amateur filmmakers inside Syria spreads valuable video stories via social media. There are also examples of graffiti collectives that exist only on Facebook. The groups collect graffiti designs created by Syrians abroad and then spray them inside Syria.

We are fascinated by how the understanding of political situations by citizens is formulated and mediated through the format of social media. However, having said that, our work is not dependent on the mechanisms of social media. We prefer to lift examples and trends based on observations from social media, in order to reformulate and place them within the context of contemporary visual art via exhibitions or publications.

NM: Does the rapid speed of events unfolding in the region, and the expiry date of news cycles influence you? Do you ever worry that the fluidity of the political events on the ground surpasses you?

FL: We are definitely influenced by the rapid speed and unpredictability of events in the region. It is not certain where the unrest in Syria will lead and as an artistic group it is virtually impossible now to formulate a comprehensive reflective response to the situation. Our work makes reference to real events in order to collect, archive, witness and analyse images and stories. We function in parallel to developments in the news but not necessarily in reaction to it. We aim to slow down what we are seeing in order to focus on details connected to the situation and connect this to larger historical and other narratives. The present Middle Eastern predicament is undoubtedly influenced by events that occurred in the past, which are particularly influenced by the west. We find it important to point out links and unexpected connections between east and west. It is certainly a challenge to constantly keep up with the relentless flow of traumatic changes and speculate what they might mean for the future. We hope that our work might offer a moment of pause.

This text was originally commissioned by the International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP) for the exhibition 'Foundland: Escape Routes and Waiting Rooms' presented at ISCP from 30 July – 26 September 2014. Please see www.iscp-nyc.org for more information.

Foundland Collective (established 2009) is a collective whose work draws on graphic design, art, writing and research. Comprised of the artists Ghalia Elsrakbi and Lauren Alexander, Foundland focuses on a critical analysis of topics related to political and locational branding through visual and written forms. Foundland’s work has been shown in exhibitions and festivals including Kadist Art Foundation, Paris (2012), Impakt Festival, Utrecht (2011, 2012), BAK, Utrecht (2012), and Visual Arts Festival Damascus, Istanbul (2013). They have given master classes and lecture presentations at Studium Generale ArtEZ, Arnhem, de Appel for Sandberg Institute, Amsterdam, Royal Academy of Arts, The Hague, Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam and at the Athens Biennial 2013. They have contributed essays and visuals to international journals such as Open Magazine (The Netherlands), Krisis Magazine (Italy), Esse Magazine (Canada) and Ibraaz. In 2013, they completed an artist residency at the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo. For more information see: www.foundland.info.

Foundland Collective is one of two participants of Edge of Arabia's first artist residency in the USA, in partnership with Art Jameel and ISCP. The residency is an integral component of Edge of Arabia's three year tour of events and collaborations across the country. More information at www.edgeofarabia.com #EOAUSA