Reviews

Midad: The Public and Intimate Lives of Arabic Calligraphy at Dar El-Nimer

Midad: The Public and Intimate Lives of Arabic Calligraphy, the third exhibition at Dar El-Nimer, is a study of calligraphy's role as a foundational art form from within (and beyond) the central Arabo-Islamic region, exploring its political, private, devotional and poetic uses in multiple contexts. Curated by Rachel Dedman, with extensive research by art historian Alain George, this is the inaugural exhibition of Rami El-Nimer's art collection, the founder of Dar El-Nimer. On display are over 75 objects that range from religious texts, calligraphic panels, talismans, amulets, ceramics, and the tools and materials used to produce calligraphic scriptures. With a diverse collection that reflects on a vast geographical terrain (from Morocco to China), and a broad historical timeline (from the eighth to the twentieth century), the exhibition's focus on calligraphic script speaks to inter-cultural histories and their cultural resonance in the present. What can be read as a two-part but interrelated show offers a rich engagement with the historical development of calligraphic practices and their material and immaterial influences on the contemporary artistic imaginary. Exhibited over two floors, the layout marks a clear distinction between museum objects in the ground floor gallery, and contemporary commissions by five Lebanese artists in the upstairs gallery, including Marwan Rechmaoui, Roy Samaha, Mounira al-Solh, Jana Traboulsi and Raed Yassin.

The exhibition begins with a brief history of the artistic development of Arabic script – born of the migration of calligraphers, shifts in printing developments, and the movement and circulation of texts – and considers calligraphy's layered histories and uses in diverse socio-political contexts. Entering the ground floor exhibition space, the white cube has been transformed into an intimate museological space. The use of partitions, vitrines and coloured walls – including a deep green and a dark red wall, intended as an extension of the colours present in the manuscripts and calligraphic panels on display – adds to the intensity of the viewing experience. Beginning with a timeline of calligraphic developments, the display moves from the early Kufic scripture (angular and architectural in style) through to the more fluid calligraphy of the Six Pens and the Nasta'liq, and the role of modern printing processes on Arabic scribal traditions. Each calligraphic style is accompanied by objects that attest to calligraphy's heterogeneous forms and uses in multiple personal, religious and cultural contexts, ranging from a single Folio from an Early Qur'an dating back to the ninth-century Abbasid Empire, to a late-nineteenth/early-twentieth century Persian Zafarnama – a book of Persian proverbs. In prefacing the exhibition with the origins and developments of the Arabic script, it seeks to direct the viewer through the impressive precision of form and artistic composition involved in its making.

Midad goes to some length to detail the role of the calligrapher, including notables such as Ibn Muqla (886–940), Ibn al-Bawwab (d. 1022–31) and Yaqut al-Musta'simi (d. 1298), and lesser known individuals, noting women's (often subsidiary) role as copiers. The calligrapher's working process is reflected in the texts themselves. This is evidenced in a calligraphy panel from the Ottoman-era (1900–1 AD) that shows subtle traces of different layering and erasures of letters that have been re-written. The instructive wall texts call on viewers to pay close attention to such details that tells of the process of production and works to demystify these historic and (often) divine objects. For example, a Qur'an (dating back to mid-seventeenth-century/mid-eighteenth-century Iran) is detailed as a palimpsest of religious practices that reveals the merging of an older Qur'anic text (cut and pasted in a new book frame) imbued with nineteenth-century talismanic practices that were added after its initial production. A similar aesthetic hybridity is seen in a late sixteenth-century album sheet depicting a calligraphy exercise from Iran containing floral motifs that is consistent with Indian illuminations, which reflects the changing ownership and migration routes of these texts. In positioning these objects as an active part of social life, Midad takes an anthropological approach to the collection – which, as Dedman noted, are pieces that have multiple lives and have existed over time and developed in different contexts.

The curatorial approach strives for accessibility, with a collection that ranges from the ornate to the everyday. We find large scale Qur'ans intended for public devotion, alongside miniature Qur'ans and small talismanic amulets to be worn on the body, for private devotional practices. In a section devoted to 'Public Faith, Architecture and Authority', architectural and textual pieces, show the range of calligraphy's use in public spaces, as 'a tool of administrative and legislative power'. These include the head of a wall fountain (1767–8 AD) with calligraphic inscription that reads 'For the well-being of those who drink' to show the piety of the commissioner and the charitable role played patrons during the Ottoman era.[1] Nearby, an eighteenth-century Qur'an on cloth from Iran, approximately four metres in length that carries the entire Qur'an stitched together in one large cloth intended for public display, attests to the monumentality of the religious scripture. Such grandeur is scaled back to include smaller-scale objects, including a Magic Bowl that dates back to late-eighteenth-century/early-nineteenth-century China that attests to the commodification of spiritual beliefs that spread eastwards. (The circulation of such religious commodities invites a reflection on the collection itself, as pieces that have been acquired through European auction houses and private investment.) Nearby, a collection of coins that date back to the Umayyad period tell the story of when the circulation of money became a way to spread the influence of the Islamic faith when the region held a Christian majority.

The collection is keen to break with assumptions that calligraphy is solely bound to Islamic culture. The inclusion of several Christian and secular texts highlight the inter-cultural makeup of calligraphic practices, such an illustrated christian hymn and psalms book from Egypt, which dates back to the eighteenth century, carries illustrations of prophets and saints inspired by iconographic paintings. Elsewhere, a devotional Islamic text about the Prophet's life from the fourteenth century sits comfortably alongside a book of christian sermons that that carries sixty-six sermons by Anthanasius, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, dating back to the seventeenth century. The representational differences in Christian and Islamic visual imagery is also detailed. Mounted on a wall, an icon painting of Saint Phillip the Apostle (eighteenth or nineteenth century) hangs next to a document that is both an ijaz (a calligraphic licence) and a hilye (a verbal description of the Prophet's physical attributes) (1852–3 AD). The latter work details the Prophet's life in a panel intended to be viewed in its entirety, which a wall text suggests, 'is akin to gazing upon a portrait of Mohammed through word, not image'. In positioning these two works in conversation, it probes us to think of the relationship between Islam's non-figurative visual approach and Christianity's figurative iconography.

Particularly striking, and arguably the most unique object in the collection is the Qur'an of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (c.1702–73), not least because the narrative by which its production came about weaves a complex history of the European slave trade in West Africa; racial politics and class hierarchies; and the centrality of recitation and memory to the writing of the Qur'an. (The Qur'an was written entirely from Diallo's memory when he was in England, a destination he eventually reached after being mistakenly captured as a slave in Bundu – modern day Senegal – where he was later freed and celebrated in English high society due to his 'exceptional' civility). The Qur'an reveals crudely penned calligraphy, as well as the rare inclusion of Diallo's portrait and biographic detail, which were added after the text's completion. Here, as with elsewhere in the exhibition, the Qur'ans rare textual quality is secondary to the personal narrative.

At the opening of the exhibition, Dedman spoke about the negotiation between curating the museum display and showcasing the objects' quotidian usages. Whilst these collected objects are locked in vitrines, which creates a viewing distance, the focus on the lives involved in the making of them animates the display. Where pages of the texts cannot be turned, screens have been placed in encasements for viewers to swipe and interact with the texts, which points to a gesture of intimacy that the exhibition seeks to foreground. Such gestures are continued in the contemporary display upstairs where, for example, Jana Traoulsi's Kitab al-Hawamish (2017) – a work that focuses on the visual coding of the text's infrastructure – has produced take-away booklets that challenge the singularity of the objects on display downstairs by allowing them to travel beyond the gallery walls.

In this contemporary part of the exhibition, each artists' response to the historic collection are varied in both style and thematic content. Roy Smaha's haunting video, A Book of Six Directions (2015), performs the unfolding of a talismanic object (on show downstairs) – made up of folded paper squares with Qur'anic script, magic diagrams, depictions of Mecca and allusions to hell – to reveal its many layers and enigmatic qualities. The transformative power of recitation is hinted at through disparate voiceovers and images that take reference from the object – ranging from whirling dervishes, the Prophet's mosque, and scenes of bustling city life in Istanbul, where the object originates from. For Marwan Rechmaoui, six small-scale paintings titled Ventriloquize, explore the linguistic resonances – or, the sub-textual meanings – of religious mysticism that persists in everyday spoken Arabic today. Through a series of paintings of jinns and spirits, Rechmaoui's paintings foreground an older epistemic knowledge that continues in the present through everyday phrases and descriptions.

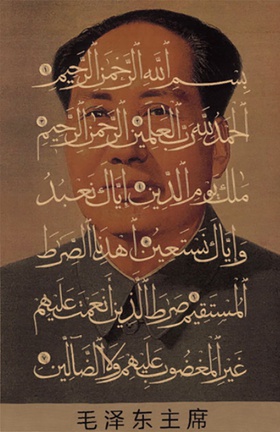

Perhaps the most visually provocative works in the contemporary section is Raed Yassin's Mao series – Mao I, Mao II, Mao III, Mao IV (2015). Hung high on the gallery walls, the mass-produced iconic images of Chairman Mao are overwritten with embroidered Surahs from the Qur'an. Given the oppression of Muslim communities in Mao's Communist China, the curatorial statement suggests that this series points to a strategy of power, in which weaving the authority of the Islamic text over Mao's image becomes a form of revenge or 'reversal' of this violent history. Yet, in a discussion held at Dar El-Nimer, Yassin offered a different reading: in his words, this series should be read a 'mash-up' that speaks to the misunderstanding and mis-characterizations of (in this context, Arabo-Islamic) cultures that creates deep ruptures in our understanding of the region. It is a valid point given the popular narrative on Islam in the media, and the physical destruction of cultural heritage and monuments occurring across Iraq, Syria, Palestine and elsewhere in the region – a narrative this exhibition seeks to challenge. That this rich collection can persuasively attest to the aesthetic diversity of calligraphy, as site where memory, history and cultural hybridity meet, points to how exhibitions can move beyond the political discourse to highlight the cultural richness of the past; a past that can be catalysed for new artistic responses in the present.