Essays

The North of the South and the West of the East

A Provocation to the Question

I

How to effectively map the historical and contemporary relationships that exist between North Africa, the Middle East and the 'Global South' is a question that cannot, in my view, be answered without reference to the accumulation of cartographic meanings that have created the image of the planet since the sixteenth century. Cartography and international law were two powerful tools with which western civilization built its own image by creating, transforming and managing the image of the world. German legal philosopher, Carl Schmitt, labelled this 500-year history 'linear global thinking'.[1] Linear global thinking is the story of how Europe mapped the world for its own benefit and left a fiction that became an ontology: a division of the world into 'East' and 'West', 'South' and 'North', or 'First', 'Second', and 'Third'.[2]

The overall assumption of my meditation is the following: the 'East/West' division was an invention of western Christianity in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries – an invention that lasted until World War II. The division was used to legitimize the centrality of Europe and its civilizing mission. From World War II onwards, there was a shift to a 'North/South' division, but this time the division was needed to legitimize a mission of development and modernization. The first part of this history was led by Europe, the second by the United States. Now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the so-called rise – and return – of the 'East' is drastically altering 500 years' worth of global divisions produced by the western world to advance its imperial designs.

The need for an understanding of this history and to decolonize knowledge, therefore, emerges from this long lasting situation of western hegemony: one that extends from scholarly work to mainstream media. This response is a modest contribution to such a decolonizing of knowledge and an attempt at understanding why such a process must happen. It will begin with the implications of naming and mapping.

II

Geopolitical naming and mapping are fictions, and fictions have creators. Take the regional name 'Maghreb'. If you look for the 'meaning' of Maghreb on the Internet in a standard search – which to my mind expresses the general understanding of the term – you will find the 'reference': that is, the name of the countries within the Maghreb. If you insist, you will find the etymology of the word, and not the reference: 'the place of the setting sun'.[3] The source will also tell you, so you do not get lost, that it is in the west that the sun sets. But to the west of what, you may wonder. It may take a while to realize that the Maghreb is located on the side where the sun sets in relation to Mecca and Medina.[4]

On the other hand, if you search for the meaning of 'Occident' (again in a standard Google search) you will find that the term incorporates the countries of the western world, especially Europe and America. If you search for the etymology, you will find that the term comes from the Latin occidentem: 'the part of the sky where the sun sets'.[5] Now, if Europe and America are countries 'to the west' then what west are they in relation to? If you continue to search, you will find out: the west of Jerusalem.

The act of naming and mapping is always an act of identification, and identification at this level requires someone who is in a position to name and map. Furthermore, effective naming and mapping can only be done from a position of power that overrules local senses of territoriality. Take Alfred Thayer Mahan, who in 1902 renamed a region that was identified in Orientalist discourse as the 'Near East' with the label 'Middle East'.[6] Thayer Mahan was not interested in people, but in natural resources and strategic geo-political mapping, and a great deal of India's territory became part of his newly identified 'Middle East'. But not everyone in the region was happy with such an identification and proceeded to dis-identify from it, making it clear that in this case, naming cartographic regions carries the weight of imperial identification. There is never a direct relation between the name and the map on the one hand, and the people and the region on the other.[7]

Here, the consolidation and expansion contained in the act of naming and mapping is not only economic and political, but also – and above all – epistemic in terms of authority, and the management of knowledge and identities. Geopolitical naming and mapping are fictions in the sense that there is no ontological configuration that corresponds to what is named and mapped. The act is possible through a control of knowledge; and it requires epistemic privilege that makes naming and mapping believable and acceptable. That naming and mapping territories and peoples creates fictional cartographies does not mean that what is mapped and named already had an ontological existence beyond its mapping and naming, either. On the contrary, they are grounded in the interests of people, institutions and languages (modern European vernacular languages grounded in Greek and Latin) who have the privilege of naming and mapping.

III

So how does this relate to the terms, the 'Global South' and the 'Global North'? Let us consider how these 'regions' are popularly perceived today on the web:

The North-South divide is broadly considered a socio-economic and political divide. Generally, definitions of the Global North include the United States, Canada, developed parts of Europe, and East Asia. The Global South is made up of Africa, Latin America, and developing Asia including the Middle East. The North is home to four of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council.[8]

Here you have an answer to the general question of this platform: North Africa is indeed located in the 'Global South'. The definition also notes that the 'Global South' includes 'developing Asia and the Middle East'. I will now set about problematizing these fictions and mappings by recalling the distribution of the planet and its inhabitants as depicted in many European maps of the seventeenth century. Let's take one at random: Visscher's world map from 1652.

What do you see in this map? Many things of course, but for the argument at hand let's concentrate on the four corner cartouches. Europe is a woman in the upper left corner, elegantly dressed and seated in a locus amenus. In the upper right corner the viewer encounters Asia, also an elegantly dressed lady this time seated on a camel (though often in such maps the camel is an elephant instead). Now let's look at the bottom left corner. It is Africa: semi-naked and seated on an unidentifiable animal; perhaps a crocodile. Finally, in the bottom left corner is America: also semi-naked and seated on an armadillo. Here, visual classification follows the visual logic of western alphabetic writing in that words move from left to right and from top to bottom. In this map, the most important native is in the upper left corner, where the most important news items in newspapers are today still located. In the upper right corner is the second in relevance. Then, at the bottom, Africa and America (exchangeable in other maps) in their semi-naked state signal a lack of civilization and a closer relation to the animal kingdom.

In this map, and thus at this time in history, the 'North/South' divide was already implied. After all, the magnetic compass was already in use to determine the four cardinal points of the globe. But before the magnetic compass was invented, the 'top' was occupied by the place where the sun rises: the Orient. That is why we say today: 'orientation'. And we say it even if we are 'orienting' ourselves with the 'North' as point of reference.

Here, let us consider Russia (the former Second World) for a moment, which was left out of the 'North/South' division. As Madina Tlostanova has argued, this is because Russia is the 'South' of the 'North'; an argument that is crucial to understanding how 'North/South' fictions operate:

The erasing of the Second World has resulted in the increased binary organization of world order and the changing of its axis to the North-South divide. Similarly, the West-East partition tends to homogenize various local histories into imagined essential sets of characteristics. Drifting of bits and pieces of the Second World in the direction of either the North or the South has become unavoidable for all its former subjects, yet leaves them with an uncertain, almost negative subjectivity. This article problematizes the role and function of the ex-Socialist world and its colonial others within the global North-South divide through the concepts of colonial and imperial differences. It considers Caucasus as the utmost case of the South of the poor North, and analyses secondary 'Australism' – a syndrome that is devastating for the subjectivity of its people. Finally, it dwells on the possible ways of decolonizing being, sensing and thinking in the non-European Russian/Soviet ex-colonies.[9]

Tlostanova's argument and the introduction of the word 'Australism' have particular and strong resonance here. It makes us aware that the 'North-South' divide is the displacement and replacement of Orientalism. In this, 'Australism' is the appropriate term to understand the invention of the 'South' as much as Orientalism was, in its time, a way to understand the invention of the Orient. Both the 'East/West' and the 'North/South' divides are not ontological but fictional, and they are also political, since they tell us more about the interests of the enunciators (institutions, people, organizations) than about what is named, classified and mapped.

But these fictions are not just games: they have real effects.

IV

When it comes to the world's divides, racism should be taken into account, though it should not be conceived as a biological issue as much as an epistemic one. Racism is a classification of difference and an organization of differences into hierarchies, which operates not only in the everyday life of nations but also at an inter-state level, and is precisely how these 'North/South', 'East/West', and 'Third World/Second World/First World' divides have operated.

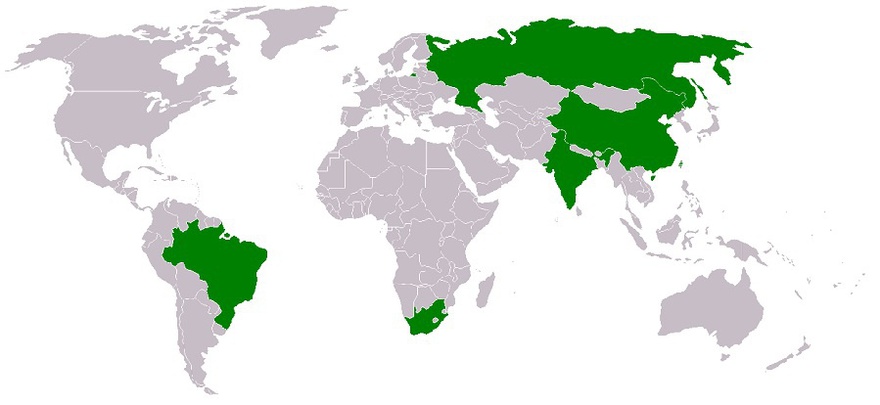

Take Huntington's logic of planetary classification as depicted in the legend from the map above. The 'West' – North America, Canada, Europe and Australia – is positioned on the top of the list, and is the civilization that classifies the remaining eight according to the following categories: 'Western', 'Orthodox' (meaning eastern Christianity), 'Islamic', 'African', 'Latin American', 'Sinic', 'Hindu', 'Buddhist', and 'Japanese'. Now consider here the mapping of Islam – the main the reason why Huntington wrote his book – and Africa. The map makes it clear that it is in North Africa and not Sub-Saharan Africa where the majority is Muslim, thus severing Black Africa and Muslim Africa from each other. Indeed, what the BRICS[10] also have in common – along with the rest of the world order after decolonization during the Cold War – is that all of them have been racialized (ranked below the 'West', the 'First World', or the 'North').

To better understand my claim, let's take a historical detour and remember the initial question: How do we effectively map the historical and contemporary relationships that exist between North Africa, the Middle East and the 'Global South'? To answer this, I shall draw a picture of the historical geo-political formation and transformations of the modern/colonial world: a historical foundation of the modern/colonial global order we owe to Pope Alexander VI. In fact, soon after Christopher Columbus landed on shores he thought were Indian, Pope Alexander VI partitioned the land and sea as was known until that year and donated them to the Castilian and Portuguese Crown. The new land partition was named 'Indias Occidentales' and the donation was stamped in 1494 in a treaty called the Treaty of Tordesillas. Thus, the Atlantic was born as a zone of commerce between the Iberian Peninsula, Indias Occidentales and Africa.[11]

About 35 years after the Treaty of Tordesillas, the monarchs of Spain and Portugal reached another agreement. That was stamped in another treaty, The Treaty of Zaragoza, signed in 1529. In this treaty, the two monarchs agreed to divide between them the eastern part of the known globe named 'Indias Orientales'.[12] (Mind you, people living in 'Indias Occidentales' had no idea that they were living in 'Indias Occidentales', for both the name and the mapping were fictions of Popes and monarchs of Western Christendom.) It was then that the 'East/West' division of the planet as we know it today was established. It was a western Christian invention, pure and simple, which presupposed a centre between two poles: Rome (the Papacy), and the two monarchs advancing the Papacy's project to Christianize the world.[13]

About three and a half centuries later, Britain took over the leadership of western imperial expansion, removed the theological connotation of Rome as the centre of the world and replaced it with the secular Greenwich Meridian. Nevertheless, by the time the Greenwich Meridian displaced Rome, the axis around the 'East/West' division was mapped. However, while Rome was simultaneously located in the 'West' and at the centre of the world, between 'Indias Occidentales' and 'Indias Orientales', London – after appropriating the position geographically located to the east of the Greenwich Meridian – was cosmologically self-located in the 'West' and therefore at the world's centre.

But it should be said that until the first decades of the sixteenth century there was not a single world map: no one had a whole view of the land and water masses that we know today. Each existing civilization (Chinese, Indian, Persian, African Kingdoms, Mayas, Aztecs, Incas, and so on) had their own spatial configuration of sky, earth, sea and under-earth. When the first global maps were devised, the previous local territorialities were subsumed and colonized by the local world map that served as the foundation of western civilization. When Pope Alexander VI drew the line of Tordesillas' Treaty, he had a previous map of the world in his mind – the medieval T-and-O map. This map presented a global view (it was not of course universal) of the world from a singular, local cosmology: Christianity.

By the mid-sixteenth century, Gerardus Mercator and later Abraham Ortelius (Typus Orbis Terrarum) drew the world map that is familiar to all of us today. But though we may tend to believe that this is what the planet looks like, it doesn't. Take Asia, Africa and Europe: these three 'continents' existed at the time only in the minds of Christians inhabiting Europe. Asians did not know that they lived in Asia until approximately 1582 when Jesuit missionaries visited China and told them that according to the Christian concept of the earth they lived in Asia![14] For that reason, embedded in the Ortelius map is the T-and-O map, and the drastic consequences of sixteenth century mapping was the disavowal and devaluation of non-western cosmologies and territorial imaginaries. The first nomos of the earth, in Schmitt's terms, was superseded by the second nomos that homogenized and universalized the belief that the planet really looked the way Christian European mapmakers of the sixteenth century believed it to look like.[15] Western cartography shuttered everyone else and made us see the planet according to the eyes of western cartographers.

Thus, the world map, though global in what it enunciates has to be, by necessity, local. The enunciation cannot be global, it is always local: the 'West' is a local enunciation that creates a global enunciated (the map we see). That is, the locus that has the legitimacy (language, institutions and social actors) of world making. But today, there is a shift. Peoples who were once mapped are remapping themselves. The emerging multipolar world emerging out from dewesternization is parallel to the pluri-versal world that is emerging from decoloniality. There is no longer a zero point of observation – the 'Global North' and 'Global West'. There is no reason to look at the world from Rome first, and the Greenwich meridian secondly. Now we are seeing the re-emergence of pluri-versality: the planet as it was before 1500.

V

From this, let us return to the previous definition of the 'Global North' and the 'Global South' as cited from the Internet. The Global North includes the United States, Canada, developed parts of Europe and East Asia. Furthermore, in the online definition, Japan and China have been removed from the 'East' and placed in the 'North'. The lesson we can get from this description is the following: until 1945 the world was divided between the western and eastern hemispheres based on civilizational criteria (Orientalism and civilizing missions led by British and French imperialism). Then from 1945 onwards, the world was divided between the northern and southern hemispheres based on economic criteria (development and modernization led by the USA).

What this tells us is that the 'North' is defined by economic and not cultural criteria. (Otherwise, it would be absurd to count eastern Asia as part of the 'Global North'). From the economic perspective of the 'North', the 'Global South' refers to regions that are 'underdeveloped' and 'emerging'. Curiously enough, from a political and decolonial perspective, the 'Global South' includes places where forces of liberation from the 'North' have been at work.

After all, to be classed as a 'Third World' – or indeed 'Southern' – person you are placed in an inferior position – third, not first. However, the situation can be reversed when you assume the place you have been allocated as a place of pride to denunciate such a hierarchical, derogatory naming – to turn it into a space of struggle and re-identification. And this is what we are witnessing and engaging in today: a global dispute for the legitimacy of western fictions in all spheres of life and knowledge. The 'Global South' became a metaphor for precisely this: the affirmation of what the 'North' devalued. The idea goes back to the Bandung Conference in 1955, when the struggles for liberation and decolonization were located in Asia and Africa: a historic gathering of 29 countries from Asia and Africa that promoted 'South-South' relations.[16] The goal of the conference was to find a common vision of the future for the non-western world that was neither capitalism nor communism, but rather 'decolonization' – a delinking from western macro-narratives.

In this changing panorama of naming and renaming, the configuration of the BRICS states is of extreme relevance here because, among other reasons, it dismantles 'East/West' and 'North/South' divides. But it would be limiting to say that this is a 'post' world order, for it would maintain the logic upon which spatial divisions were arranged within linear time in which the 'North' and 'West' become the starting point. On the contrary, it is 'de' in this case: dewesternization – not 'post' because it is not a move within the linear concept of time, but the re-turn, re-surgence, and re-emergence of ways of living, thinking and doing that were disavowed by both western modernity (in the past 500 years, from western Christianity to western secularism) and post-modernity.

BRICS states are, within the current divide between 'North/South' and 'East/West' both in the 'North' and in the 'South', but also in the 'East' and in the 'West'. Yet, to modern and postmodern ways of thinking it would be impossible for the BRICS countries to form a viable union of any sort because they do not have common languages, common religions, are not in contiguous territories, do not have a common memory (like ancient Greece and Rome for all western countries), and their people look, act and feel differently. Common sense (modern and postmodern) supposes that people who do not have much in common and are only bound together for and by economic interests cannot remain together for long.

The BRICS do, however, share profound commonalities that hold them together, and from a decolonial perspective the commonalities are obvious: strong historical memories of western incursions and invasions. Three current states (India, Brazil and South Africa) have been formed over the ruins of previous western imperial colonies (the British, Portuguese, and Dutch and British settlers respectively). In South Africa the Dutch had settled since 1652, but the full colonization of Africa (including, of course, North Africa) started around 1870 and it was achieved after the Berlin Conference of 1884.[17] China was never colonized but did not escape coloniality: the nineteenth century Opium Wars were the strategy Britain, with the support of France and the USA, used to undermine the Chinese government and population. Russia was never colonized either, yet has a long history of being viewed as a 'second-class' empire parallel to the rising history of western civilization and imperialism.[18]

In the case of Brazil, India and South Africa, these were colonies of the Portuguese and British Empires. The fact that Brazil, contrary to India and South Africa after Nelson Mandela, is ruled by people of European descent rather than by natives (like in India and South Africa), evinces a difference of scale rather than of nature. It is a long story to account for here, but the fact that political scientist (and author of Clash of Civilizations) Samuel Huntington would place Latin America (which of course includes Brazil); and he locates Australia in the 'First World', revealing how people of British and Portuguese descent are seen from the perspective of the 'First World' or the Global North. It is not by chance that China invited South Africa (after Mandela) to join the BRICS, and not Australia. [19]

Thus, what these five BRICS states have in common are the experiences of western imperialism and therefore of the infliction of imperial (Russia and China) and of colonial wounds (India, Brazil and South Africa). Briefly, colonial wounds refer to racialization and dehumanization of colonized and enslaved human beings (Aztecs and Maya civilizations, for example, and enslaved Africa in the sixteenth century and India in the nineteenth century). Imperial wounds are a derivation of the former and refers to regions and people who were not colonized or enslaved but that were, nonetheless, devalued as human beings: the Ottoman Sultanate in the sixteenth century; Russia, (both Soviet Union and Russian Federation with different justifications at different times) and China (particularly since the Opium War).

Imperial and colonial wounds are neither visible nor quantifiable. When it comes to North Africa and the Middle East, it is certain that colonial and imperial wounds are present, too: on a quotidian basis and in various forms – geopolitically, religious, artistic, epistemic. The reactions and responses to such wounds occur at different levels: from the decolonial energy of North African 'intifadas' to the dewestern drives manifested by museums and biennials of the Gulf States, which have used the term 'Global South' as a form of re-existence and self-affirmation (Re-emerge was the title of Sharjah Biennial 11) from the clouds projected upon them since the expulsion of the Moors from Spain in 1492.

In this light, let us change the question to this: where is 'North Africa' and the 'Middle East'? I shall write these names in quotation marks to remind you that they are fictions. The 'Near East', for example, was a translation of the French expression Proche-Orient, and referred roughly to the regions under the control of the Ottoman Sultanate at the beginning of the twentieth century. But by 1922, the Ottoman Sultanate collapsed under constant pressures from England and France, imperial leaders at the time, and was dissolved. This collapse brought about the Republic of Turkey, which is now counted in the so-called broader MENA, though technically it is located in western Asia.

Iran has a different history: the history of the mutations of the Persian Shahanate (misleadingly called 'empire' for the Shah was not an Emperor for the same reasons that an Emperor was not a Shah – this observation is already a small example of re-merging pluri-versality). Modern Iran traces its history to the end of the Safavid dynasty (1501 to roughly 1736), which was located in Baku in present-day Azerbaijan. An Islamic state, Iranian dynasties run from 1736 to 1979, when the Iranian Revolution ended the system of dynastic government. But in looking at Iran, which today will most likely continue its alliances with Russia in the North, and with Indonesia and Malaysia in South East (emphasis mine) Asia as well as Turkey, we see that a state that emerged from the ruins of the Ottoman Sultanate (to which current Iraq also once belonged) is also located in a region conceived as 'West Asia'.

Indeed, in the first quarter of the twenty-first century, the world order is being remapped in a way that cuts across 'North/South' and 'East/West' divides. In this I see three trajectories unfolding.[20] Two of them are undoing and redoing the chrono-topic (time and space) world order of the past 500 years, and one of them is insisting on controlling the privileges of naming and mapping to maintain the mono-polar world order. These three trajectories have different temporalities but they are all related to the long history of westernization,[21] from the emergence of the Atlantic Commercial Circuit in the sixteenth century to the return of China in economy and the issue of 9/11 in politics. Today, the structure and division of the world according to western imagination and interests is being disputed.

Pulling away from western dominance, the politics of BRICS states and other emerging economies of the Middle East (Turkey) and south-east Asia (Indonesia) have profiled one of the rising trajectories: dewesternization. Economic growth brought self-esteem and confidence in the political arena, to 'former Third World' and 'people of colour', and provided the energy and creativity to overcome racial hierarchies (regions and people) invented and implemented during five hundred years of westernization. But of course, actors and institutions in the western world do not want to lose the privileges gained over the centuries. Thus, the second trajectory: rewesternization – an attempt at maintaining a world order with a power centre that is located in the western world.

Here, I would just mention one variable: while rewesternization is diminishing middle class consumer privileges, dewesternization is creating an enormous middle class with consumer privileges. In both cases, the gap between concentration of wealth and expansion of poverty is disproportionate. Rewesternization (the expansion of the 'Global North' and 'West') is what the world is witnessing in Ukraine and in the Middle East. Dewesternization is also visible in Ukraine in the politics of the 'North' and the 'East' (and the politics of 'Orthodoxy' in Huntington's classification).

The third trajectory I see is decoloniality, but decoloniality is not a state-related project, as is the case with dewesternization. It is, rather, a project from a new global actor: an emerging political society[22] defined and self-identified through well thought-out organization. In the twenty-first century, we have seen the politicization of civil society in different and complex ways. There have been the 'intifadas' in North Africa and the Middle East, the 'indignados' in the south of Europe, from Greece to the Iberian Peninsula, as well as the recent politicization of peoples in western Asia (Turkey and Ukraine).[23]

Decoloniality is part and parcel of the emerging global political society, and it is enacted in two dimensions: one operates in the sphere of (for lack of better word) social movements. The other operates in the sphere of artistic, scholarly and intellectual endeavours. Both spheres are components of the emerging global political society, and the main goal of decoloniality in this domain, is to decolonize the state to liberate the form of governance. Decolonial responses do not dispute the control of the colonial matrix but propose to totally delink from it by imagining something that does not rely on hierarchical, racial and economic divisions. In fact, the decolonial approach is therefore a way of being in the world that could be carried out in the 'North', 'South', 'West' and 'East', for the simple reason that western coloniality is not only over, but it is all over.[24]

VII

So where does this remapping leave us? At the borders: physical, epistemic, ethic, religious, psychological, and aesthetic. Dwelling in the borders creates the conditions for border thinking, doing and being. That is, for border epistemology, praxis and ontology. Why? Firstly, because you also cannot ignore and/or avoid westernization and rewesternization for the simple reasons that both are unavoidable. Figments of western cosmology are all over the world; it is in all of us. Consequently, dewesternization requires border thinking to dispute the control of coloniality for it cannot just 'apply' western ways of doing things to ways of knowing, doing and being. It is not about either submitting or adapting, but delinking: moving in a different direction while recognizing that different directions cannot be followed simply by forgetting what 500 years of western theological and secular branches of knowledge – the arts, philosophy and the sciences, for instance – have achieved, from education, governmental systems and economic practices.

This means that today and in the future, decoloniality will no longer be identified with the 'Global South' but it will be in the interstices of a global order that was once divided into 'East' and 'West' and more recently 'North' and 'South'. Furthermore, decoloniality is not 'post' to anything since decoloniality is the sum of those unrecognized responses towards global imperial designs that have been expressed and enacted since the sixteenth century. Decoloniality, without being named as such back then, co-existed with the westernization of the world (1500–2000) as today it co-exists with the processes of dewestrnization and rewesternization. Decoloniality carries the spatial 'de' from the borders of global designs; it is the relentless energy of re-existing, re-emerging and re-making, and not the uni-linear temporal 'post' that celebrates the superseding of the old by the new.

[1] Carl Schmitt, The Nomos of the Earth. In the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum, trans. G.L. Ulmen (Candor, NY: Telos Press Publishing, 2003). Originally published in 1950.

[2] It is important to note that the coloniality of naming continues. In recent news it was commented that the French state doesn't accept the name of 'Islamic State' because is not a legal state. Nevertheless, the west continues to name what happens beyond its frontiers: the Orange Revolution, the Arab Spring, The Umbrella Revolution.

[3] Nouri Gana, 'North Africa (Maghreb)' in The Encyclopaedia of the Novel, ed. Peter Melville Logan (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2011), p. 456.

[4] Mehdi Cyaxares, 'Maghreb,' Ancient Worlds website http://www.ancientworlds.net/aw/Places/District/820172.

[5] 'Occident,' Online Etymology Dictionary http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=occident.

[6] 'Where is the Middle East?' Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations website http://mideast.unc.edu/where/.

[7] Sahar el-Nadi, 'Middle East of What?' in The European, 18 March 2012 http://www.theeuropean-magazine.com/sahar-el-nadi--2/6181-the-long-history-of-a-label.

[8] Italics author's own. See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North%E2%80%93South_divide.

[9] Madina Tlostanova, 'The South of the Poor North; Caucasus Subjectivity and the Complex of Secondary "Australism,"' in Global South, 66 5.1 (2011).

[10] BRICS is the commonly used acronym for the five major emerging national economies: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

[11] No one had a clear vision of the position and form of Indias Occidentales land masses, but in a contemporary visual sketch, this is what the Treaty of Tordesillas could be perceived as: http://srufaculty.sru.edu/james.hughes/201/Andes-Mexico/images/treaty.gif.

[12] By 1530, the planet, mapped by the Pope and the Crowns of the Iberian Peninsula looked more or less (because no one had at that time the image of the planet we have today) like this: http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-T3eDVJSns1A/T533RNgRwtI/AAAAAAAABAU/NWB-oO5jzP4/s1600/treaty+of+Tordesillas.jpg.

[13] Partition among imperial powers runs the logic of coloniality, hidden under the rhetoric of modernity. What was initiated in the sixteenth century was replicated in 1916 when England and France (rather than Spain and Portugal) divided among themselves the 'Middle East'. This time the treaty was called an 'agreement' and given the name Sykes-Picot, see: http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/History/sykes_pico.html.

[14] Caitlin Lu, 'Matteo Ricci and the Jesuit Mission in China, 1583-1610' in The Concord Review (2011): http://www.tcr.org/tcr/essays/EP_TCR_21_3_Sp11_Matteo%20Ricci.pdf.

[15] I explored this issue in detail in 'The Movable Center: Ethnicity Geometric Projections and Coexisting Territorialities,' in The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality and Colonization (MI: University of Michigan Press, 1995), pp.219-259; and the issue of the 'nomos' of the earth in Walter D. Mignolo, 'I am Where I Do: Remapping the Order of Knowing,' in The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), pp.77-118.

[16] Norma Giarracca, 'Re-emerge: the return of the Global East and Global South. An Interview with Walter Mignolo,' Walter Mignolo website, 22 June 2013 http://waltermignolo.com/re-emerger-el-retorno-del-lejano-este-y-del-sur-global/.

[17] Ehiedu E. G. Iweriebor, 'The Colonization of Africa,' Africana Age website http://exhibitions.nypl.org/africanaage/essay-colonization-of-africa.html.

[18] See Madina Tlostanova, 'Book Review: Internal Colonization. Russia's Imperial Experience,' Postcolonial Europe, May 2014 http://www.postcolonial-europe.eu/reviews/166-book-review-internal-colonization-russias-imperial-experience-.html.

[19] Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996).

[20] This view is quite different from that recently advanced by Henry Kissinger, as you can see from his new book World Order (New York: Penguin Books, 2014).

[21] Serge Latouche, The Westernization of the World: Significance, Scope and Limits of the Drive Toward Global Uniformity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1996).

[22] Mongrel, 'Partha Chatterjee, "On Civil and Political Society in Postcolonial Democracies,"' blog entry, Notes on Scholarly Books blog, 1 May 2009 http://notesonscholarlybooks.blogspot.com/2009/05/partha-chatterjee-on-civil-and.html.

[23] I use 'intifadas' and 'indignados/as' to avoid the uni-versalization of one name for all. We shall know already what happened with maps and naming regions and people. Properly we should name each insurgency of a civil society by their local name.

[24] I take this expression from Michelle K in 'Decolonial Aesthesis: From Singapore, to Cambridge to Duke,' Social Text/Periscope (2013): http://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonial-aesthesis-from-singapore-to-cambridge-to-duke-university/.